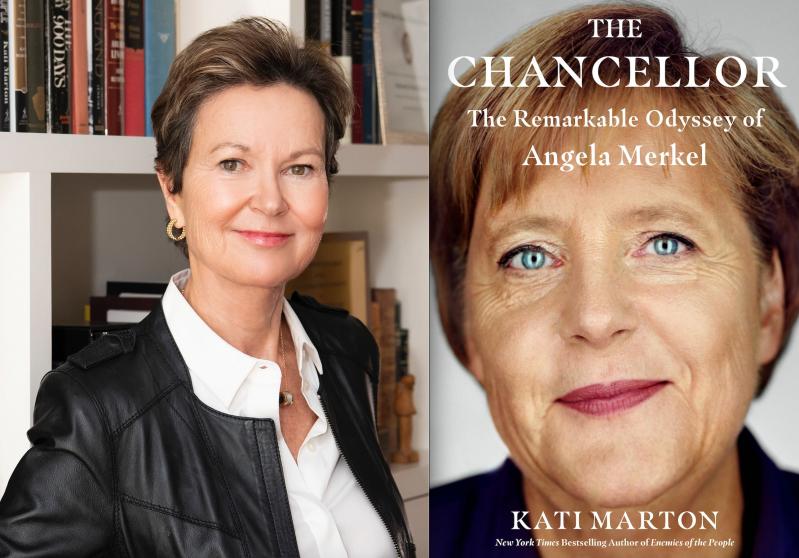

“The Chancellor”

Kati Marton

Simon & Schuster, $30

Keine gute Tat bleibt unbestraft. Yes, the Germans say it, too. "No good deed goes unpunished."

And one wonders if that expression ever crosses the mind of Germany's departing leader, Angela Merkel, whose character and manifold good deeds are so deftly and sympathetically described by the author and broadcast correspondent Kati Marton in "The Chancellor."

Probably not. Ms. Merkel is renowned for her ego-free approach to politics and leadership — calmly calculated, often poll-driven, ready to compromise if at times a bit too restrained.

As the first woman and first East German to head the government in Berlin, in four terms over 16 years, Ms. Merkel led her nation further than ever from the lingering shadows of Third Reich shame and guilt to a new moral high ground ("her conviction that Germany's debt to the Jewish people was permanent," Ms. Marton writes) as well as to economic power and political influence across the European Union that she was determined to more solidly unite, and around the wider world.

It was a world that clearly benefited from her providing more German counterweight to significantly less involvement by America under Donald Trump, and the lingering threat of our returning to Trump policies if not to the man himself.

And yet Ms. Merkel is still criticized for the austerity she enforced on less productive, less parsimonious European nations in exchange for E.U. financial aid in the global fiscal crisis of 2008, though she later backed outright grants as well as loans for such poorer nations to counter the Covid crisis.

"Merkel, you are not welcome here," proclaimed banners when she visited Athens in 2012, Ms. Marton reports, adding: "The most dangerous by-product of this period, however, wasn't the blow to Merkel's image. It was the birth of the first successful post-World War II German far-right political party, the Alternative fur Deutschland (AfD), which was founded in opposition to the EU's bailout of Greece [to which] the rise of modern populism in Germany and elsewhere can be traced."

Germany's new far right was further strengthened by reaction to Ms. Merkel's moral mandate that Germany open its doors to a million mostly Muslim refugees. Neither Germany's budget, nor its welfare or education systems, was overwhelmed, Ms. Marton notes, but she must admit that the anger that catapulted the AfD into the Bundestag "remained a slow-burning fuse in German life."

And while Ms. Merkel's response to the first wave of Covid in Germany itself was quick and scientific (as befit her early career as a quantum chemist), more-threatening variants and a slow response by individual states forced her to warn that the pandemic's current wave is "worse than anything we've seen." But her call for a major lockdown was opposed, at least initially, by the incoming administration as likely to seem a "bad political trick."

One of Ms. Merkel's last major efforts was engaging with increasingly powerful China, as distasteful as its brutal, undemocratic ways were.

But a historic package of complex E.U.-Beijing agreements on trade, finance, climate, and human rights that she oversaw (largely over flickering Zoom screens because of the worldwide pandemic) was seen by too many as too favorable to Germany in particular, and too tone deaf to "China's increasingly harsh rhetoric and policies," as Ms. Martin has to acknowledge in a final footnote — noting that the European Parliament put the pact on hold (probably until 2023, according to recent press reports).

And this year, Ms. Merkel's center-right Christian Democratic Union (C.D.U.), heart of her ruling bloc, suffered its worst-ever election defeat, narrow to be sure, despite her record of achievements, though arguably also because she herself was not running.

Well suited to tell this story, Ms. Marton also spent her earliest years under Soviet Communism (in Hungary) and observed German politics and politicians both as a journalist and, later, as wife of the late Richard Holbrooke, former U.S. ambassador to Germany and the U.N., assistant secretary of state for Europe, and special Balkan envoy.

As she details it, Ms. Merkel's rise seems a triumph of temperament, talent, and timing.

Her father, a stern and demanding Lutheran pastor, moved the family from West to East Germany — pre-Wall — to provide what ministry he could without challenging Communist domination.

Buoyed by Bible reading, but a very personal form of Christian faith, Ms. Merkel came to see the importance of love as "serving." And serving, she realized early on, required power.

So albeit determinedly shy ("Highly gifted," recalled one teacher, but "She never smiled!"), Ms. Merkel became "a leader from the beginning," says a childhood friend. "If there was something that needed to be organized, she took care of it."

She was fascinated by the outside world, poring through biographies of European statesmen and scholars, grabbing copies of the only English-language publication available, from Britain's Communist Party, becoming the first in her school to wear "that sartorial symbol of the decadent West, blue jeans."

Frustrated by the repression and depersonalization of the Communist system, she told herself: "I will not have my life ruined. If I can't bear it anymore, I will go to the West, somehow."

Science was her first escape route, specifically physics, having perceived that even harsh East German Communism "wasn't capable of suspending basic arithmetic and the rules of nature."

During her university studies in Leipzig, she first joined the Club der Ungekussten (Club of the Unkissed), then married a fellow student, Ulrich Merkel, departing after three years but keeping his name and earning a doctorate.

A 1981 trip to Poland, as the independent Solidarity labor union there began shaking up the Soviet empire, filled her with enthusiasm. When the Wall came down in 1989, she headed west, first just a few jaunts, then plunging into politics to join a new era of change in Germany reunited.

At the new East German party Demokratischer Aufbruch (Democratic Departure), she was noted for quiet modesty and take-charge competence: noticing a stack of sealed crates, opening them to set up the party's computer system, then rising in its ranks.

Her can-do but nonthreatening manner did the same for Ms. Merkel when Demokratischer Aufbruch merged with the C.D.U., led by then-Chancellor Helmut Kohl, soon looking to balance his administration for a newly unified nation with someone from East Germany, and a woman (presumably in tune with growing female activism).

"Pick Dr. Merkel. She is the most intelligent," Kohl was advised. And she became minister of women and youth, though not happy as Kohl still liked to call her his Madchen, or young lady (not as patronizing as it seems to me, I was assured recently by another East German woman).

Kohl had already lost his bid for a fifth term as chancellor when, in 1998, a scandal broke over past campaigns that would force him out as C.D.U. chairman. And his former Madchen was not disposed to defend him. "The time of Party Chairman Kohl is irreversibly over," she wrote in a major newspaper.

Two years later Ms. Merkel won the top party post unopposed. Eventually reconciled, Kohl endorsed her winning (narrowly) bid for chancellor in 2005. And in 2014, he sent what Ms. Marton calls "double-edged greetings" on her 60th birthday: "You seized opportunities that your varied life has offered you."

And so she did — whatever price she has had to pay for her unique mixture of pragmatic politics, high ideals, and personal privacy. Neither loyal staff nor foreign dignitary has ever visited the rent-controlled apartment she and her second husband, also a scientist, share in central Berlin.

And there she may well stay — enjoying her reading, walking, cooking, evenings at the theater, opera, or concerts, Ms. Marton concludes; likely considering inevitable offers to join councils of the formerly powerful, or do-good nonprofits.

For her formal farewell last week Ms. Merkel requested a Christian hymn, an East German punk hit, and a song with the line "Let me encounter new wonders, let me unfold anew from the old."

Kati Marton lives in Sag Harbor and Manhattan.

David M. Alpern hosted the "Newsweek on Air" and "For Your Ears Only" radio broadcasts for more than 30 years, now lives in Sag Harbor, and moderates Zoom presentations for local libraries, the latest a tribute to the novelist John le Carré for the Hampton Library in Bridgehampton on Sunday at 2 p.m.