“Plunder”

Cynthia Saltzman

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $30

History doesn't typically link art to politics. But when a masterpiece becomes the protagonist of a story, art transcends prescribed movements, canvas, and paint, and the circumstances of its creation and provenance.

In her new book, "Plunder: Napoleon's Theft of Veronese's Feast," Cynthia Saltzman traces a High Renaissance work — Paolo Veronese's "The Wedding Feast at Cana" — from its inception to its role in the rise of the French Republic, uncovering it as a symbol of victory and cultural entitlement.

Commissioned by the monastery of San Giorgio Maggiore outside Venice in 1562, "The Wedding Feast at Cana" depicts a scene with some 130 figures, in which Christ turns water into wine, his first miracle. Veronese "never put his brush in the wrong place," according to an early biographer. Among Venetian colorists, Veronese was "second to none," Ms. Saltzman writes, competing against elder artistic giants such as Titian and Tintoretto. Centuries later, Vincent van Gogh would develop his radical theories of color in part from his study of the Italian master.

"The Wedding Feast at Cana" — a vast 22.2 by 32.6 feet — would require a laborious installation on the monastery's refectory wall; its appropriation by Napoleon's proxies more than 200 years later came perilously close to destroying it. That the painting was understood as a masterpiece was undisputed. And so, in spite of the risks to its survival in moving it, it naturally became part of the new Louvre museum, the former palace of Bourbon kings. At the Louvre the Emperor Napoleon would exhibit his European plunder, along with royal and private collections seized during the French Revolution.

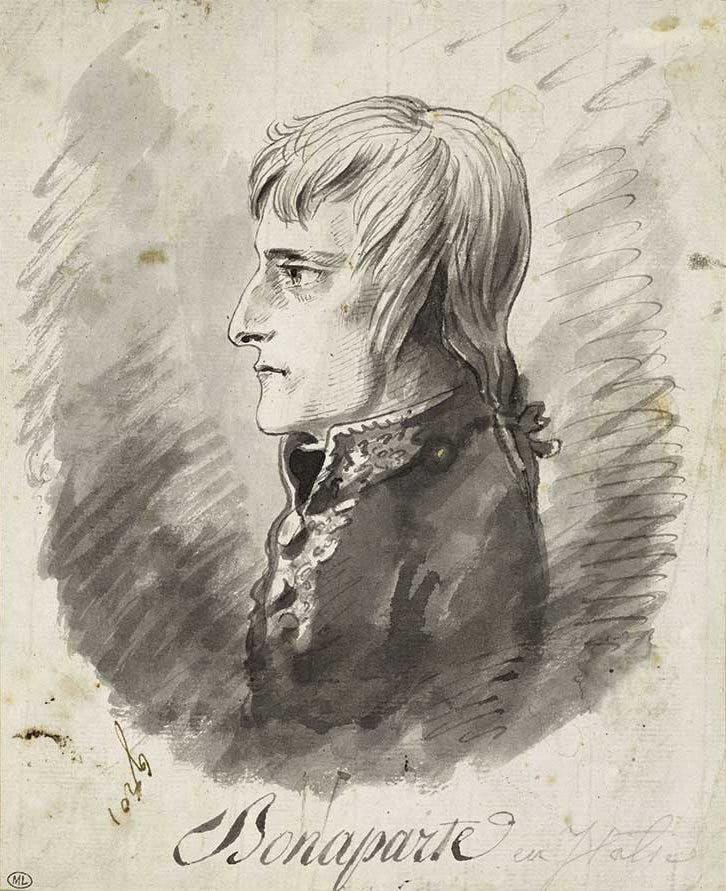

A former Wall Street Journal and Forbes reporter, Ms. Saltzman is the author of "Portrait of Dr. Gachet: The Story of a van Gogh Masterpiece, Money, Politics, Collectors, Greed, and Loss" and "Old Masters, New World: America's Raid on Europe's Great Pictures" — books in which she uses art, sometimes a single masterpiece, as a springboard to examine the time, place, and the people it touched and motivated. "Plunder" focuses primarily on Napoleon's Italian campaign, beginning in 1796, in which it was his object to acquire "everything of beauty" as certainly as it was to expand his empire.

"What did Napoleon know of art?" asks Ms. Saltzman — an interesting question. "He knew that in France, the visual arts were inextricably linked to political power," she writes, "that Louis XIV and other French kings had few rivals in their extravagant collecting and patronage of painting and sculpture, and in exploiting art to aggrandize their reigns."

The completion of the Louvre, in which art would ostensibly belong to the people for the first time, was "brilliant testimony to the superiority of the new regime over the regime of old," according to the French Republic administrator Armand-Guy Kersaint. Napoleon cast his thefts as the "liberation" of art, and the French Republic as "the rightful heir to genius."

In Ms. Saltzman's fresh perspective, Napoleon, the quick-thinking tactician, had a driving ambition to "prove himself an intellectual and a scientist." Parma, Modena, Milan, Bologna, Rome, and the separate state of Venice fell to his armies as did their Raphaels, Titians, Correggios, da Vincis, and Michelangelos; the spoils were carted away with as much ceremony as might triumphant contestants in a game show.

Turning his attention to Egypt, then part of the Ottoman Empire, Napoleon brought along 160 French scientists, engineers, artists, and intellectuals to gather artifacts and information. "There can no longer be any question of what Napoleon wants," observed Archduke Charles, brother of the Austrian emperor, as this self-anointed emperor chipped away at the Habsburg monarchy. "He wants everything."

"Plunder" is brief, just 232 pages, before footnotes and color plates. Still, in the spare details Ms. Saltzman chooses, the characters come alive. Paolo Caliari — called Paolo "Veronese" after the city of Verona, the place of his birth — became rich from his art, but, we learn, he "lived away from luxury" in Venice in a four-story house "with a plain facade" with his wife and children. Yet in his extravagant feast scenes he captured the material wealth and cosmopolitan life of the city.

In a 1660 poem, Marco Boschini called him "the painter of beautiful things" that, adds Ms. Saltzman in her elegant prose, seem more beautiful than the things themselves. But the artist lived in particularly tricky times.

Veronese's mix of the religious and the secular presented a conflict for some. Subsequent to "The Wedding Feast at Cana," the Dominicans commissioned the artist to paint "The Last Supper" for their refectory wall, later deeming the work heresy. The artist was called up before the Inquisition for promoting apostasy, atheism, and Judaizing, among other charges. Veronese humbly defended his work, echoing the Roman poet Horace: "Painters and poets have always enjoyed the right to take liberties of almost any kind.

More practically speaking, he pointed out that a "picture with some space to spare" requires surplus figures and objects. He shrewdly renamed the canvas "The Feast in the House of Levi."

Characters who would have escaped notice in a traditional history assume large roles in "Plunder," among them the Italian painter and restorer Pietro Edwards, who had served for two decades as the inspector general of public pictures in Venice. After devoting his life to "saving" Venetian pictures, he "was thrust into the unexpected and onerous role of assisting the French in removing those same pictures" — a dilemma that spins out into pages of gripping narrative.

Then there is the artist Antoine-Jean Gros, another intriguing player, who, seized with the ambition to paint Napoleon, achieves his goal through the careful cultivation of Josephine, the emperor's wife. The artist Jacques-Louis David, familiar as the neoclassical hero of art history studies, is equally the ruthless Jacobin revolutionary in "Plunder." David voted to send Louis XVI to the guillotine and signed some 400 arrest warrants as a member of the Committee of General Security.

Readers will flinch at Ms. Salzman's vivid description of the removal of "The Wedding Feast at Cana" from San Giorgio Maggiore's refectory wall as it tumbles from its frame, tearing row upon row of holes across the canvas. The painting has been moved since repeatedly — five times during World War II alone to evade bombing and Nazi looting.

That Veronese's "The Wedding Feast at Cana" hangs in the Louvre today, across from da Vinci's "Mona Lisa," is due, of course, to plunder and the miracle of luck, careful conservation, and its many champions over time.

Ellen T. White, former managing editor at the New York Public Library, is the author of "Simply Irresistible," a book about romantic women in history. She lives in Springs.

Cynthia Saltzman has spent summers in East Hampton all her life. She lives in Brooklyn.