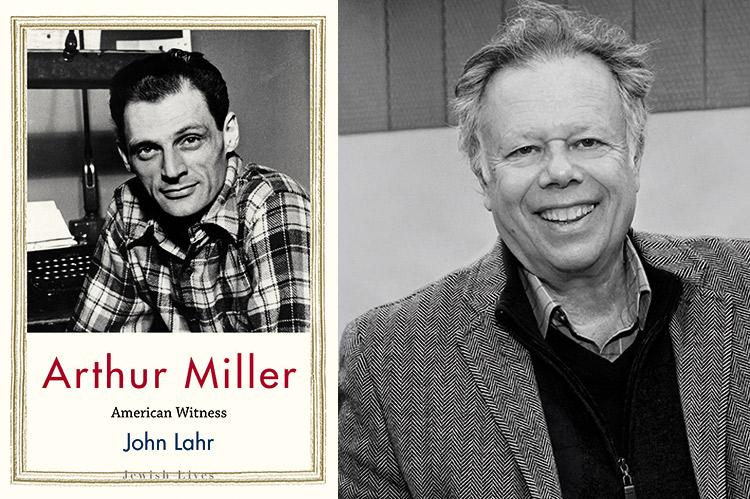

“Arthur Miller: American Witness”

John Lahr

Yale University Press, $26

Following the first performance of Arthur Miller's "Death of a Salesman" in February of 1949, the playwright thought he had a dud on his hands. The audience sat in stunned silence. "There was too much crying," he said.

As John Lahr reminds us in his new biography, "Arthur Miller: American Witness," the tears were the manifestation of something large, a "profound wellspring of loss he tapped into." This was a post-Great Depression, post-World War II audience, and through Willy Loman, their grief erupted. Finally, after the crowd had gathered itself, there was an explosion of applause and countless curtain calls. It was a titanic success.

If "Death of a Salesman" is not the great American play, then it is on the shortlist of three or four. This sent the talented, but erstwhile unassuming, playwright on a tumultuous trajectory. Now, with this admirably brief book, Mr. Lahr, a prominent theater critic, delivers a no-filler biography that still leaves room for his keen critical insights. There are windier, more comprehensive bios of Miller, but mostly everything is here. None but the most ardent of the playwright's fans will need more.

Born in Harlem in 1915, Miller was an admittedly terrible student with a chaotic home life. His father, Isidore, was a well-to-do women's clothing manufacturer whose marriage to Augusta was mostly a financial arrangement. The dysfunction turned out to be great writer's fodder. Mr. Lahr observes, "In order to survive the indigestible confusions of his family's dynamic . . . he developed a fictionalizing habit of mind."

When the stock market crashed in 1929, most of Isidore's wealth was erased, leaving the family, as Mr. Lahr writes, "dazed, discombobulated, and unmoored." "The scar never left him," the critic continues. "Throughout his writing life . . . Miller would pick at the sore."

Eventually he would begin writing short stories, and more important, radio plays. Mr. Lahr tells us that Miller claimed to have a "very aural imagination." "What I hear," he asserted, "means more to me than what I see." His decision to become a Broadway playwright would bedevil him in his 20s; he produced a string of plays, but none caught hold with the public imagination.

Changing gears, he produced a novel, "Focus." It attracted some attention and modest financial reward. Buoyed by this, Miller decided to take what he called his "final shot" at Broadway.

"All My Sons" was his first classic play, and was directed by Elia Kazan, with whom Miller would share a turbulent lifelong friendship. Kazan would also direct "Death of a Salesman," which would appear two years later and cement Miller as an iconic American playwright. So universal and indelible is the work that it is speculated a production of the play is running every day, somewhere, around the globe (there is a very good one on Broadway right now). Mr. Lahr reminds us that with 11 million copies sold, it was "perhaps the most successful American play ever published."

"Death of a Salesman" brought Miller a Pulitzer Prize and made him rich and famous in a way that playwrights will probably never be again. It also, he admitted, changed him forever. Mr. Lahr writes, "Success opened his eyes and awoke his appetites." His life entered its turbulent phase.

Joseph McCarthy's House Un-American Activities Committee was already running out of steam when it called Miller to the stand in 1956. The playwright had applied for a routine passport, which prompted the committee to publicly grill him about his early left leanings. It was publicity for the committee, of course, but there was also the matter of revenge: Miller had penned "The Crucible" three years before, a dark drama that drew analogy between the Salem Witch Trials and McCarthy's own crusade.

Oh, and Miller was also having an affair with Marilyn Monroe at the time. Mr. Lahr recounts the story of the night before his HUAC testimony, when the couple were told that if Monroe agreed to pose for a picture with a committee member the interrogation would be called off. The couple refused, and Miller filibustered through the hearing, refusing to name names.

This public charade was not without its humor. Asked if he knew that one of his own plays had been produced by Communists, Miller famously answered, "I take no more responsibility for who plays my plays than General Motors can take for who rides in their Chevrolets." Kazan, who testified years before, had named names. The director claimed it was necessary to save his career, but Miller put their relationship in the freezer.

Perhaps even more chaotic was Miller's marriage to Monroe. Their affair was romantic and erotically charged; marriage was another matter. Marilyn needed constant attention, hating when Miller went off to his study to work. (She was actually quoted as asking, "What the hell is he doing in there?") Then there was her drinking and drugs. This led to screaming matches, temper tantrums, hospital visits, and all the rest. By the filming of the movie "The Misfits," the script Miller wrote for Marilyn as a gift, she refused even to be photographed with him.

After five years, it was over. She "defeated me," Miller said. "If there was a key to her despair I never found it." Still, the playwright kept revisiting her in his work time and time again. "A View From the Bridge," "After the Fall," and "Finishing the Picture" all confront Monroe in one way or another. Mr. Lahr asserts that Miller was haunted by her his entire life, unable to stop trying to fix, dramatically at least, what had broken.

As a writer Miller was never quite as good again. Had he already said everything he had to say, or had Marilyn taken something out of him? There were the occasional exceptions, of course: the satisfying 1968 drama "The Price," for example, which reckons with Miller's relationship with his father and brother. And then in 1987, as Mr. Lahr says, "Miller's major literary achievement of the decade was 'Timebends,' a prolix memoir which nevertheless took its place among the best books in its genre."

He kept writing, well into his 60s and 70s, and often stumbled. The critics were merciless. John Simon, ever the charmer, announced, "The world's most over-rated playwright." Tearing into a new Arthur Miller play became critically de rigueur. It was the usual story, born of envy. The man who wrote the great American play and had been married to Marilyn Monroe — it was almost too much luck. The critical reckoning lasted till the end of his life.

Those voices seem long forgotten now. What survives are at least three indelible American plays, and Miller the playwright as a 20th-century giant. John Lahr's "American Witness" reminds us why we'll never forget.

Kurt Wenzel's novels include "Lit Life." He lives in Springs.

Arthur Miller and Marilyn Monroe summered in Amagansett for a time in the late 1950s. Miller died in 2005.