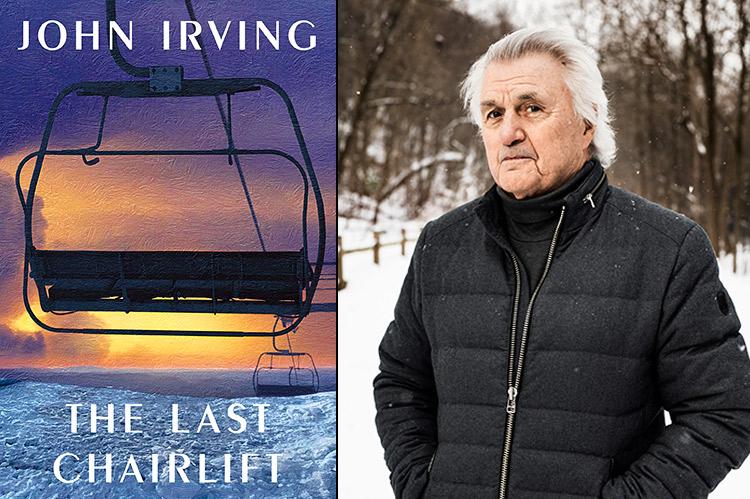

“The Last Chairlift”

John Irving

Simon & Schuster, $38

Audacious. Thematically. Emotionally. John Irving's "The Last Chairlift" is a literal blockbuster. Weighing in at 900-plus pages, in many ways the book calls to mind 19th-century works by Balzac, Zola, and Dickens. But just as those observers focused on the crises and cruelties of their days, Mr. Irving is focused on the justices and injustices he has witnessed in his lifetime.

Yes, there are cavils from readers about the length of this tome, but it's his novel, his wrestling mat, his snowshoes. And the author of "The World According to Garp," "The Cider House Rules," "A Prayer for Owen Meany" has decided he is going to speak all of his pieces.

Adam, the narrator, is conceived in Aspen's Hotel Jerome when his mother, Little Ray, went to compete in the 1941 U.S. National Downhill and Slalom Championships. She doesn't receive a medal — she's so small she doesn't have enough physical gravitational force to win. But she is a passionate skier and remains an instructor throughout her life. She is also passionate about keeping her secrets regarding her son's father.

As a boy, for six months of the year Adam Brewster lives with his mother's family — her sisters and grandparents — in New England while his mother is off teaching snowploughs and ollies out west. Rather early in the novel, Adam, then 13, rides in a Beetle with an Exeter English teacher who is a snowshoer because at 4-foot-9 he was too small to ski. The snowshoer quotes Dickens, then, once he pulls into the Brewster driveway, he delves into the glove compartment and pulls out a much-annotated copy of "Great Expectations."

He explains that he never drives without "an emergency novel" in his car. "If I drive off the road and am lying upside down in a ditch, unable to move my legs or get out of the car, I want to have something good to read." So many parallels in Adam's lonely young life and Pip's. Adam, like Pip, talks directly to the reader throughout. " 'Great Expectations' . . . would become my emergency novel."

Throughout "Chairlift" surprising event follows astonishing event. One wouldn't want a detailed outline of the novel's complex structure, except to consider the work's important explorations of family structure, sexuality, and sexual identity. As always in Mr. Irving's work, the dialogue is crisp, the pacing — yes, despite the length — is schussing perfect.

As an adult, Adam becomes a screenwriter. Mr. Irving won an Academy Award in 1999 for his screenplay adaptation of "The Cider House Rules," a film that starred Michael Caine. More of Mr. Irving's audacity? He includes screenplays within "The Last Chairlift"'s narrative.

Near the end of this Rabelaisian romp, Adam obtains his Canadian citizenship — just as Mr. Irving recently has in his nonfictional life. Adam and Em, a person who had refused to speak for years, are together. Leaving a Toronto coffee shop they're unsure as to whether the priest who has just bought their breakfast is real or a ghost.

"Our reflections in the storefront window were transparent — we could see through each other," Mr. Irving writes of Adam and Em. "We knew we wouldn't retire; writers can't stop writing. But one of us would die first. I hoped it would be me — my head on my desk, in the middle of a sentence Em would finish for me. She knew me well enough. I didn't want to find Em with her head on her desk. I couldn't imagine finishing Em's last sentence. There are no mountains to climb in Toronto — no last chairlifts for Em and me, only last sentences."

Mr. Irving's novel in some ways feels like a fictional version of Somerset Maugham's memoir, "The Summing Up." Maugham published that book when he was 64, examining why he became a writer, analyzing his thoughts regarding ethics, philosophy, religion during his more than six decades. "Fact and fiction are so intermingled in my work," he wrote, "that now, looking back on it, I can hardly distinguish one from the other."

In "The Last Chairlift," which Mr. Irving claims will be his "last long novel," he is summing up eight decades of themes, events he has explored and wants to continue tying together. He's extraordinarily articulate about his political beliefs and his views about presidents from Eisenhower up to the 2016 election. Near the end of the novel he excoriates cardinals who protected pedophile priests. By name.

"What do we want most when we're children, and crave more when we're old?" Mr. Irving asks near the end of the novel. "Consistency is what counts the most. We want the people we love to be consistent, to stay the same — don't we? I can't really tell Em what I feel about my mom, because Em has no reason to love her awful mother — nor should she. We're alone in the way we love our mothers, or in the way we don't."

Mr. Irving's epigraph is from Shakespeare's "Measure for Measure": "If I must die, / I will encounter darkness as a bride, / and hug it in mine arms."

" 'Hug the dark, sweetie,' " Adam's mother tells him, " 'and the dark will hug you back. . . . But the dark has other dates to make, sweetie — and if you don't hold her tight she won't wait around all night.' "

" 'The dark is a she?' I asked her, but my mom was gone. Little Ray didn't wait around. She just vanished, like a ghost."

"I try not to think about the vanishing."

Indeed Mr. Irving is not vanishing. He has told his publisher that he will not write another "long" novel. But he is certainly speaking of future "shorter" novels.

Lou Ann Walker, a professor at Stony Brook Southampton's Lichtenstein Center, is executive editor of the literary and arts journal TSR: The Southampton Review. She lives in Sag Harbor.

John Irving formerly had a house in Sagaponack.