“Harold Rosenberg: A Critic’s Life”

Debra Bricker Balken

University of Chicago Press, $40

A self-declared outsider, the renowned essayist and art critic Harold Rosenberg (1906-1978) rose to prominence in the 20th century to become one of the most essential voices in the discourse of American art. In a new biography, "Harold Rosenberg: A Critic's Life," Debra Bricker Balken tells the story of Rosenberg's ascent from Brooklyn's Erasmus High School to the annals of cultural history.

Along the way she elucidates the drama of New York's political ferment beginning in the 1930s, its fractious literary community, and the emergence of modernism. The author's ability to decipher the entanglements of a cultural milieu that emerged from this intellectual hotbed is remarkable, and her historical precision alongside some 15 years of research is especially noteworthy. Ms. Balken's writing is compelling and evenhanded, illuminating some of the last century's most conspicuous intellectual scuffles, social convolutions, and cultural progress with stunning lucidity.

Brainy, headstrong, and possessed of a fierce intellect, the young Harold Rosenberg was, in today's parlance, a nerd. A gawky teenager, his intellectual prowess made him quick to bore and largely inaccessible to his peers. He grew to a hulking 6 foot 4 inches with eyes set off by wooly black brows and a nasally, high-pitched voice. Feeling ostracized by his upscale classmates, he retreated into his books.

Of his childhood, Rosenberg said he "never had any dreams or ambitions," and thus he trudged through Brooklyn Law School with not the slightest interest in law. He graduated in 1927, and soon after contracted osteomyelitis, a serious bone infection, which caused him to walk with a cane for the rest of his life. After convalescing in the hospital for over a year, Rosenberg experienced a conversion of another kind, embracing a bohemian lifestyle that led him to Manhattan. There, he placed himself among the radical thinkers who hung out on the steps of the New York Public Library.

Often remarking that he got his education on those steps, Rosenberg studied Karl Marx, became a poet, and commenced the study of politics, literature, art, and culture while commingling within the political stew of Marxism, Trotskyism, and Stalinism, among other ideologies. Though he would continue to paint until his 30s, writing became his métier.

Penetrating the untold machinations of New York's literary world requires tenacity and a thick skin, qualities Rosenberg learned on the streets of Harlem, where he spent his early childhood. He was a scrappy, independent thinker whose keen intellect paved his way throughout life. Fascinated by Marxism (a fact not lost on the F.B.I. during the McCarthy era), Rosenberg argued its tenets with aplomb, but could not reconcile the loss of individualism espoused by Marx.

This period would mark the evolution of Rosenberg's theses regarding modernism, the rise of abstraction, and the very act of creation. Later, he would coin the term "action painting," embraced by Abstract Expressionist painters such as Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, and Mark Rothko. In the seminal essay "The American Action Painters," published in ARTnews in 1952, Rosenberg championed the very act of painting. His assertion that the greatest power of art lay in the creative act placed him in exact opposition to the formalist theories of Clement Greenberg. A cold war between them would last for decades.

During the 1930s, he wrote book reviews and poetry, and, in 1932, married May Tabak, who supported the couple through the uneasy years of the Depression. Eventually, he was hired by the Mural Division of the Works Progress Administration, where he met and worked with artists the likes of Arshile Gorky, Alice Neel, David Smith, and Lee Krasner, also briefly acting as Willem de Kooning's assistant at his Union Square studio.

Rosenberg's scholarship and quick mind were undeniable, and he steadily advanced in the literary world. But by 1939, war would rage in Europe, forever altering New York's cultural landscape. Still, his work and writing continued alongside the perpetual sword fighting within the literary arena. He held court in nearly every conversation while flexing his prodigious intellect.

Ms. Balken has a special gift for unraveling historical detail, and throughout the text she recounts the shifting cultural alliances in America's political, art, and literary circles with dramatic clarity. Many of the last century's cultural giants make cameo appearances, among them the French Existentialists Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, the activist and author Mary McCarthy, the ARTnews editor Thomas Hess, the philosopher Hannah Arendt, the artists Philip Guston and Stuart Davis, and the founder and editor of Poetry magazine, Harriet Monroe. Here and there, Ms. Balken dispenses a few references to who was sleeping with whom, and in this regard, Rosenberg was no exception.

In 1944, Rosenberg and Tabak purchased a small house in Springs. Situated on five acres off Neck Path, the house had few amenities and no indoor plumbing. But the couple and their small daughter, Patia, thrived there. The next year, Lee Krasner and Jackson Pollock bought a home on Springs-Fireplace Road, followed by Isamu Noguchi, Max Ernst, and Peggy Guggenheim, whose gallery, Art of This Century, had impacted Manhattan's art world mightily. Then came Willem and Elaine de Kooning, Motherwell, Franz Kline, Saul Steinberg, and Perle Fine, as well as regular visits from poets of the New York School, among them John Ashbery, Frank O'Hara, and James Schuyler, each a force in art criticism.

The summer community erupted with beach barbecues, kids, and the legendary softball games that would eventually split into two teams, the artists versus the writers. In the 1960s, the games moved to the home of Annie and Syd Solomon, whose yard offered a flatter playing field. The Springs community was fluid, shifting each year with new artists, writers, and bohemians. But it remained a constant for Rosenberg and Tabak, who would divide their time between Springs and their New York apartment on East 10th Street for the remainder of Rosenberg's life.

Postwar American culture was acutely aware of the potential for conflict, now facing the reality of the nuclear bomb. Artists, writers, philosophers, educators, and many in the general public emerged from war with a call to regroup. In 1947, Rosenberg, Motherwell, the architect Pierre Chareau, and the composer and theorist John Cage embarked on an independent journal called Possibilities. Though only one issue of the journal would be published, it resonated in the postwar climate. The writing conferred an independence on the creative world, urging its constituents to work from within and to avoid political or academic platforms. It also connected the well-known abstract artists from Lower Manhattan with those working in East Hampton. And it helped to cement Rosenberg's footing as one of the country's most formidable intellects.

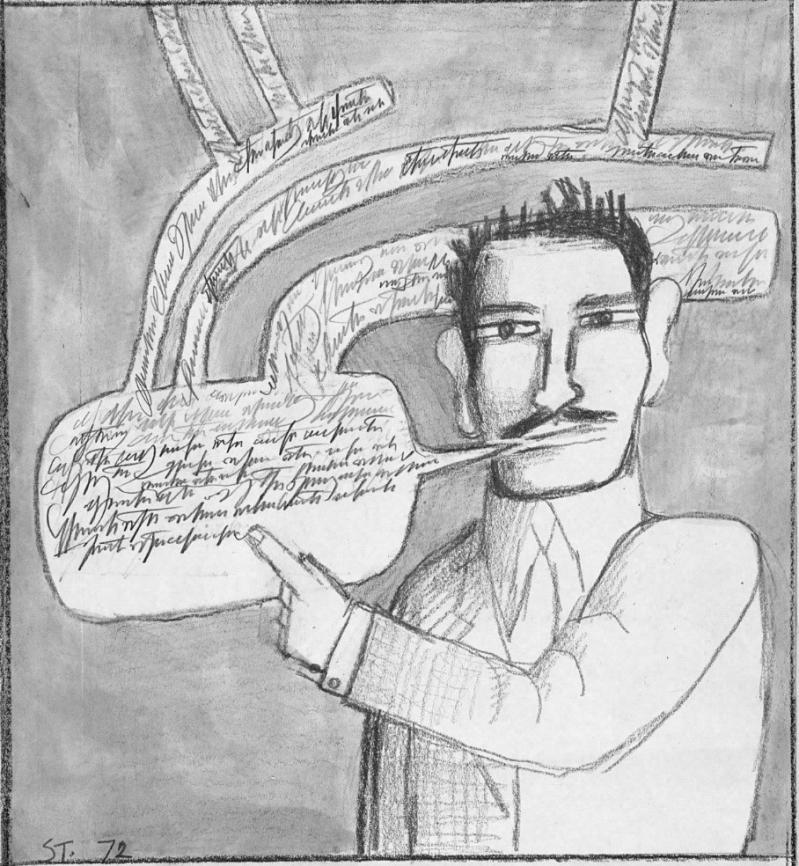

Around the same time, Rosenberg and Saul Steinberg developed a close friendship. By 1961 they were neighbors in Springs, and the two men spent hours in labyrinthine conversations. "Steinberg portrayed Rosenberg in numerous caricatures," writes Ms. Balken. "He depicted his friend as an industrious writer, and as a self-assured, imposing personality, his game leg stretched out in one cartoon to emphasize his conquest of physical frailty, or as a raconteur, his voluble conversation caught in a speech bubble."

In 1959, a collection of Rosenberg's essays, "The Tradition of the New," was published, and it would catapult him to the cultural apex as the authority in art criticism. " 'The Tradition of the New' occupied the critical limelight for almost three years," Ms. Balken writes. "In 1962, Clement Greenberg had finally had enough of Rosenberg's omnipresence and could no longer contain his anger. He had been waiting for a decade to avenge himself upon 'The American Action Painters,' knowing that he had been obliquely targeted in the essay." In the end, Greenberg's tantrum may have served only to propel Rosenberg further up the mountainside.

Despite his ascendance, Rosenberg was discouraged that he had yet to secure an editorial appointment. But in 1962 he began writing for The New Yorker, and by 1967 he would become resident art critic there. For the first time in his life, he had a steady income, a regular beat, and as lofty a perch as there was in art criticism. He would hold this position and the podium it offered until the end of his life, when, at the age of 72, he suffered a stroke and died at his home in Springs.

Ms. Balken writes, "After Rosenberg's death in 1978, Steinberg hung a photo of him in his meditation room so that 'the conversation with Harold could continue.' "

Janet Goleas is an artist, curator, and writer who lives in East Hampton.