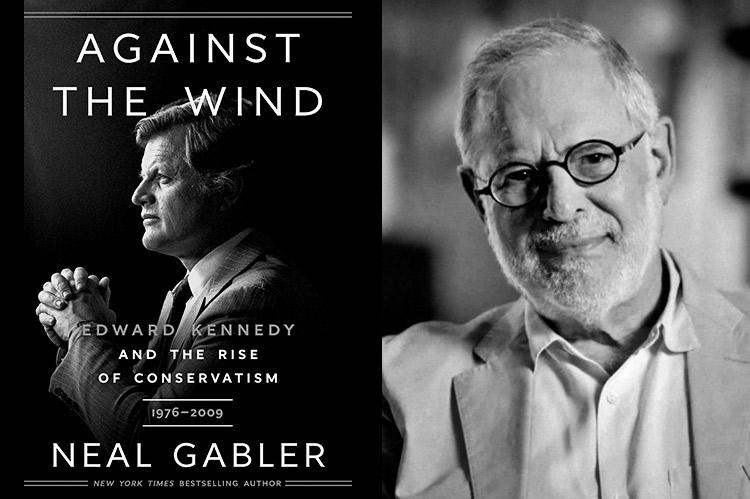

“Against the Wind”

Neal Gabler

Crown, $45

When last considered by The East Hampton Star — the Dec. 3, 2020, edition — Ted Kennedy was running.

Not for president, though that thought was for decades rarely far from his thinking or that of other politicians and a public that long presumed that Kennedy — before his death in 2009 at age 77 — would follow the path trod by his slain elder brothers John and Robert.

No, at the end of Volume One of Neal Gabler's monumental (938 pages), immersive, warts-and-all biography, "Catching the Wind: Edward Kennedy and the Liberal Hour," we saw the surviving Kennedy, in September of 1974, "literally running for his life" from an angry mob of Bostonians, many likely his former supporters, now furious that he backed public school busing to further racial desegregation.

It was for Mr. Gabler a moment that symbolized a change in the wind for Kennedy and American politics generally, from Left to Right, catching Kennedy off balance.

In his new Volume Two, "Against the Wind: Edward Kennedy and the Rise of Conservatism" (1,227 pages), that political shift becomes even more pronounced and problematic, stymying Kennedy to greater and lesser degrees under Republican Presidents Reagan and both Bushes, of course, but even with Democrats Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton in the White House. Elected as moderates, both feared that a "bleeding heart" badge on Kennedy's progressive priorities would preclude the bipartisanship to which they aspired.

Still Ted persevered, ending his nearly 50-year legislative career as perhaps the most productive U.S. senator ever, Mr. Gabler argues: 2,500 pieces of legislation sponsored, 700 passed. A "Lion of the Senate," even critical colleagues admitted that "he got things done."

Not in the manner of Lyndon Johnson when he ruled the Senate, as extensively chronicled by the sometime East Hamptonite Robert Caro — "an intimidator and a wheedler," as Mr. Gabler paints him, feared for "his power to manipulate and his power to deny." Kennedy, especially after giving up White House dreams, relied on "the soft power of congeniality and eventually even of legislative integrity."

He kept his goals — and his word.

And, with or without legislative clout, Ted consistently raised his voice — in official Senate hearings or, when Republicans ruled the turf, through less formal "forums" with impressive experts — to capture public attention for critical issues including the disastrous war in Iraq, brutal apartheid in South Africa, the call for a worldwide "nuclear freeze," and, on the domestic front, public education, immigration, the minimum wage, voting rights, AIDS, cancer, and health care coverage — especially for children.

A devoted sailor for enjoyment and escape, Ted knew how to read the winds, and initially tried to trim his liberal sails here and there. But as Mr. Gabler demonstrates, reading the wind didn't guarantee that Kennedy could outrun it, or bend it to his intended destination — always toward a nation more just, fair, and caring for those less fortunate and discriminated against, with himself in the White House or not.

Once again, Ted's tale is replete with inner conflict and contradiction.

A Kennedy born both to special blessings and burdens, strength and weakness, he was raised to believe (more or less correctly) that he was not only the last but the least of the Kennedy clan, and so developed the humility and deference that served him well as a young senator completing his brother John's term — respecting his elders with endless favors and gestures, devoting staff to the vast research necessary for him to master details of major legislation, the complex mechanics and emotional chemistry necessary to enact it, colloquy, compromise.

The fondness for liquor that could bring Kennedy grief also ingratiated him with old bulls on Capitol Hill who loved their after-hours booze. The one time I met him, in a session with Newsweek editors, Ted ordered rum and Coke, which I later was told he drank "when he isn't drinking."

And it was not by slight or oversight that through all his decades in office he kept the same rear desk on the Senate floor, happy not to highlight his ever-increasing seniority, the better to know and influence each newly elected crew of members, observe the machinations of their elders, be close to the cloakroom where key deals could be done more privately.

The presumption of his ultimate presidency, while it lasted, surely gave extra heft to Ted's many progressive pursuits in the Senate, but could also foster contradictory suspicion of ulterior motives.

Then, too, there was the disturbing — to some delicious — difference between the moral force of Kennedy's policy pursuits, his devoted churchgoing, and his well-known drinking and womanizing during and after his first marriage.

Noticing a photo of Ted leaning over some babe in a boat, we learn, Alabama's Democratic Senator Howell Heflin once joked: "Well, Teddy, I see you've changed your position on offshore drilling" — perhaps the funniest line in a book that sometimes reads less like history than oratory, hortatory, lots of rhythmic repetition on his subject's behalf.

Of Kennedy's watery car crash on Chappaquiddick Island that killed a female campaign staffer late one July night in 1969 — and which he failed to report for 10 hours — there is little new, and no mention of published reports that Kennedy actually might not have known that Mary Jo Kopechne had gone to sleep in the back seat of his black Oldsmobile. What we see is how the cloud it left over Kennedy could never be totally dispelled, in his own mind or the public's — although Mr. Gabler sees it more as a growing, hostile (or audience-building) media obsession.

But the question of character would have to become more relevant as his 1980 challenge to the nomination of the incumbent, Carter, took shape, then folded.

And that same moral cloud was clearly a factor keeping Kennedy unusually restrained at the 1991 Senate Judiciary Committee hearings for the Bush Sr. Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas — especially after Anita Hill, his former aide, alleged that he had sexually harassed her.

Another factor was the media frenzy over a recent rape charge against his nephew William (Willie) Kennedy Smith (later found not guilty) after Ted most unwisely took him and his son Patrick out drinking very late one night in Palm Beach.

The role Justice Thomas plays in today's cultish conservatism makes Ted's constraint then even more chilling.

But Mr. Gabler notes there was also important political — and moral — motivation. It was a Thomas mentor and main supporter in the Senate, Republican John Danforth of Missouri, with whom Kennedy was then working on new civil rights legislation against workplace discrimination. A true conflict of (progressive) interests.

Mr. Gabler details how Kennedy could draw criticism at times for not compromising his liberal core convictions, and at other times, from other liberals, for giving up too much ground to get at least something passed.

Surprisingly, it turns out that for all his passionate, persuasive public rhetoric — on the floor and in numberless rallies around the country and outside it — Ted's muttering to staff and friends was sometimes incomprehensible.

And despite his merrily boisterous, often bellowing style in politics and social life — tirades on Capitol Hill, old Broadway tunes around the piano — we learn that Ted by himself could often seem down, shadowed by the legacy of brothers he never felt he could quite match, even more so as the mythology about them overtook even their actual accomplishments.

Then they — and he — came to be seen less as leading lights than lightning rods in an increasingly conservative ideological storm.

The storm traced back at least as far as Nixon and Reagan, campaigning and in office, playing on racial and class divisions, demonizing government itself as the enemy, especially federal spending on the poorest as periodic economic woes — from job offshoring to the home mortgage debacle — plagued a pinched working class.

There was as well a cultural backlash against coastal elites and what could be portrayed as the anti-family, moral decline starting in the 1960s — sexual liberation, women's liberation (and promotion), then legal abortion with the Supreme Court's 1973 Roe v. Wade ruling, now reversed.

And the author notes a "new media ecology" with endless hours of right-wing radio shows, the start of 24/7 TV news, later the internet, all fueled by extreme political personalities and angry polarization of the sort the G.O.P. firebrand Newt Gingrich fomented, winning back Republican control of Congress in 1994, overlapping the disparate disaffected and "turning conservatism from a gaggle into a movement."

What most worried Kennedy, Mr. Gabler writes, was that his ceaseless struggle for individual rights and liberties had an unintended consequence, "the breakdown in the community of caring," as Ted once told a New York Times reporter.

Another sad irony, we learn, was that despite his years of promoting equal health care coverage for mental illness as for physical, Kennedy was, sadly, less sensitive closer to home.

Said his son Patrick, for years a Democratic congressman from Rhode Island despite serious drink, drug, and emotional problems: "He didn't understand the chronic mental condition I struggled with. He often said that all I needed was a 'good swift kick in the ass.' "

They finally reconciled when Ted, diagnosed with incurable brain cancer, released his son from the pressure of politics in the Kennedy tradition: "You know you don't have to run for public office anymore. You can do what makes you happy."

It was more difficult for Ted to fully free himself from a lifetime of struggle and service. In his final months, mostly in Florida or Cape Cod, increasingly incapacitated, Ted still stayed in touch and struggled to the Senate floor when called to cast the deciding vote against a 2008 George W. Bush administration plan to cut fees for Medicare doctors — with a shouted "Aye" and a thumbs up, Mr. Gabler notes.

Later that summer, Kennedy achieved a "secret goal" of speaking at the Democratic National Convention in Denver that would nominate Barack Obama — foreseeing "not merely victory for our party, but renewal for our nation," and lifting the crowd to its feet.

He was back in Washington after the election to spotlight yet another effort to expand health care that he had helped organize remotely, and to counter pressures on Obama to deprioritize it. And back again two weeks later for Obama's inauguration — "a great day," he told everyone, despite the bitter chill.

He returned again in February when his vote was essential for a new economic stimulus bill. "Kennedy reporting for duty," he announced. And two weeks later, for both a Kennedy Center celebration of his 75th birthday and to help pass expansion of his 1990 National and Community Service Act (which led to the domestic AmeriCorps), renamed the Edward M. Kennedy Serve America Act.

Kennedy would not live to see passage of the health coverage expansion he had so long sought, now dubbed Obamacare, nor publication of the memoir on which he worked along with his last political projects, "True Compass," which Mr. Gabler says helped Ted finally accept himself emotionally, accomplishments and contradictions.

His longtime friend John Kerry, the former junior senator from Massachusetts whom Kennedy backed for president in 2004, said that Ted at the end told him "he felt it important that he provide an example for others of how to die, which was living life to the fullest and without regrets." And, as this densely detailed book makes dramatically clear, so he did.

Neal Gabler, who lived in Amagansett for many years, now lives in Maine. Ted Kennedy and his second wife, Vicki, regularly sailed to Sag Harbor for their anniversary.

David M. Alpern, a former reporter, writer, and senior editor at Newsweek, for more than 30 years, also anchored the "Newsweek On Air" radio broadcast, later the nonprofit "For Your Ears Only" show, and now hosts programs for local libraries in person or via Zoom from his home in Sag Harbor.