“The Profession”

Bill Bratton and Peter Knobler

Penguin Press, $30

For those who missed his 1998 autobiography, "Turnaround," Bill Bratton's current memoir, "The Profession," provides an excellent recap — and why not? Both were co-authored with Peter Knobler, the collaborator much sought after by such as James Carville and Mary Matalin, Sumner Redstone, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, and Tommy Hilfiger. "Peter captured my voice," Mr. Bratton acknowledges.

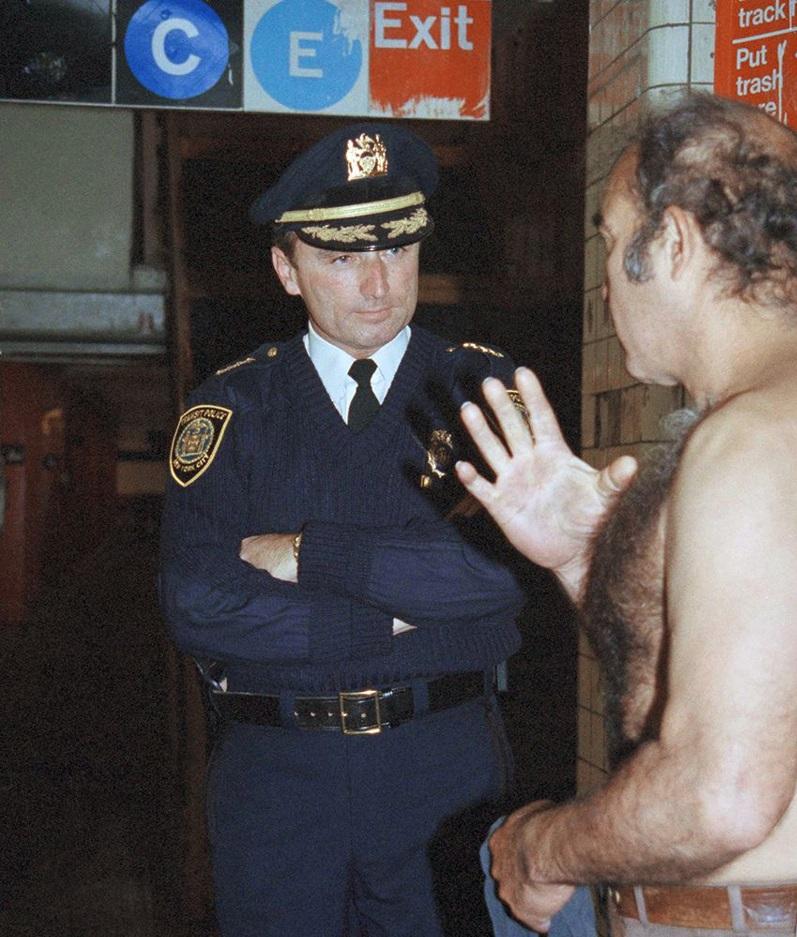

And so both men again have shared the sharing of Mr. Bratton's extraordinary law-enforcement career — top cop in Boston, Los Angeles, and New York City (twice) — with a record of dramatic crime reduction, an aura of sensitive, sensible, practical moderation, and a knack for charming across invisible fences.

"You see us. You really see us," a beloved neighborhood activist called "Sweet Alice" told him as he left the L.A. post. "The highest praise I have ever received," he calls it.

What's new in this volume is an inside look at Mr. Bratton's second incarnation as commissioner in New York, starting in 2014, albeit with a little reminder about the end of his first, in 1996, when then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani, not yet comfortable with second-fiddle status, felt outshone by Mr. Bratton making the cover of Time.

There's also some finger-wagging at the commissioner he returned to replace, Ray Kelly — and former Mayor Michael Bloomberg — for over-escalating some trademark tactics of Mr. Bratton's first Big Apple stint. Most notable: his "stop, question, and frisk" campaign, despite the record low levels of crime to which it had led, that subsequently made it both unnecessary and counterproductive — antagonizing the noncriminal majorities in many non-white neighborhoods.

Like the body count of enemy forces killed in Vietnam, "stop-and-frisk" stats became the sign of success for cops, their commanders, and the department, not necessarily related to actual crime. Bratton 2.0 brought those numbers down with no criminal upsurge.

All of which sets the stage for the most useful, if complex, aspect of this book as we follow Mr. Bratton's analysis and engagement with a variety of 21st-century challenges to the profession of policing. These include increasing social and political polarization, growing recognition and concern over racial inequality and injustice, the greater amplifying and distorting role of media — especially social media — when it comes to dramatic, sometimes tragic, police encounters.

And, of course, the ubiquitous cellphone with its power to document such incidents, quickly organize angry, sometimes destructive protests around them, adding momentum to Black Lives Matter and similar responses, and to the call for police "defunding" in its various definitions and degrees. Think George Floyd.

"Among the cops and their unions there is a widespread belief that all police reformers are antipolice," Mr. Bratton writes. "This is wrongheaded; I'm a police reformer and I defy anyone to call me antipolice."

He insists, repeatedly, that the vast majority of cops are decent, honest, fair, and of necessity braver than most all other public servants are ever forced to be (firefighters clearly another exception). But he also admits there are bad apples, absent or insufficient training, and "implicit bias" that can shape behavior (and misbehavior) from street beat right up the chain of command.

"In New York City, the Black population is a little over 24 percent, but 85 to 90 percent of the people who shot police are Black," he writes. "So there are two kinds of bias. There is conscious, unregenerate racial bias. And there is implicit bias" — based in reality — which might have a cop thinking: "I know that every time a cop is shot, there is an 85 percent chance, at least in New York City, that the perpetrator is a male Black."

And so Mr. Bratton takes us through an elaborate training course developed for his N.Y.P.D., now taken up by departments across the country, to make officers aware of how implicit bias and unconscious stereotyping can be both wrong and counterproductive — prompting tougher than needed tactics that frustrate and alienate the law-abiding.

It's serious stuff, but there are some laughs as well to keep the cops engaged. One comes early on with the video of a British TV talent show and a dumpy, matronly woman whose first appearance has police eyes rolling, until she starts to sing — like an angel.

"They took one look at her and made an assumption: This woman is unintelligent, she is not talented, she is a slob, she can't sing." But of course Susan Boyle could. "And the moral of the story: We all have our implicit biases."

Chosen as an adviser by incoming Mayor Bill de Blasio, then as his top cop, Mr. Bratton also considered the psychology of citizens by maintaining "quality of life" policing around the city while modernizing strategies for more serious law-breaking, and deploying the predictive capability of new CompStat computer technology to pinpoint what kinds of crimes were being committed, where, how many, and by whom.

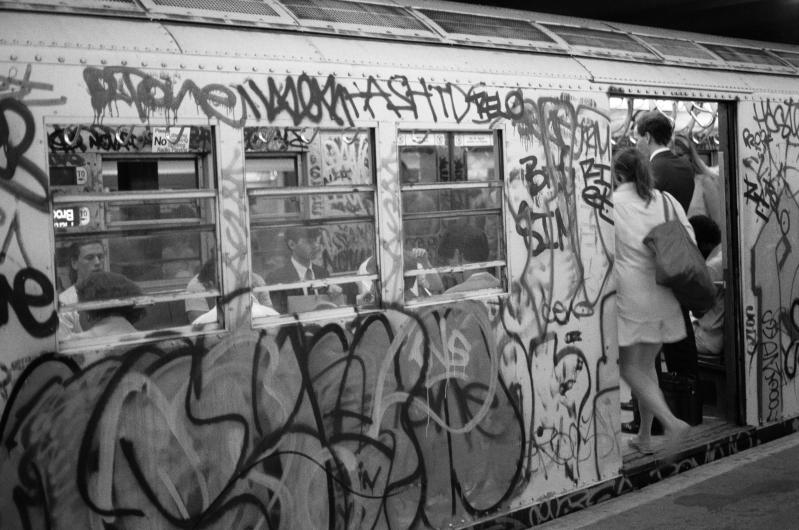

"Broken Windows" was the title of an Atlantic magazine story by the academics George L. Kelling and James Q. Wilson, arguing that just as the dilapidated appearance of a building suggests that nobody cares about it, so does commonplace neighborhood disorder — public drinking or drunkenness, panhandling, gang activity, prostitution — suggest that government doesn't care, making citizens fearful and encouraging perpetrators to pursue yet higher levels of criminal activity.

That led to "quality of life policing" targeted on low-level disorder to make citizens feel better in the moment as smarter, tougher strategies work to make them actually safer.

"Community policing" sought input and participation by local residents and their leaders. "Neighborhood policing" anchored the same officers to the same sectors within precincts, "day in and day out, [making them] intimately involved with their people, problems, and potential," Mr. Bratton explains.

"Precision policing" (not the goose step variety) grew out Commissioner Kelly's Operation Crew Cut that targeted the "violent crews [gangs] that were disproportionately responsible for shooting and homicides" and expanded to focus on the relative few committing the majority of all violent crimes, "rather than the tens of thousands who weren't. Those categories of crime dropped significantly," the commissioner is pleased to note.

Far more complex for police planning is the challenge of terrorism, imported or home grown, inspired and guided by a tsunami of online extremist ideology and know-how (bomb-making 101?). Mr. Bratton praises the N.Y.P.D. intelligence team created under Mr. Kelly, "designed, honed, and built by thirty-year CIA veteran David Cohen [as] a combination of the FBI and CIA," including plenty of potential undercover agents (the N.Y.P.D. has personnel from 142 countries, speaking 159 languages), networks of informants, "and foreign posts all over the world."

To which Mr. Bratton and his longtime deputy John Miller, formerly of ABC, CBS, and the F.B.I., eventually added a Critical Response Command with 1,300 more cops, heavy weapons and protective gear, and intensive training in rapid anti-shooter and anti-terror tactics that suddenly seemed essential after stunningly brief but bloody Islamist attacks on the Charlie Hebdo newspaper and Bataclan theater in Paris.

Mr. Bratton takes pride in the cases of terror investigated from tips and clues, digital and otherwise, then prevented — or prosecuted to conviction. Still, he admits that "anyone who tells you that they can prevent every terrorist attack in an open and free society doesn't know the world."

All the new threats and complexities make him fume over demands to "defund" policing — as prevention or punishment for systemic racism, real and misperceived — though he wouldn't mind handing off some social service burdens (the homeless, addicted, mentally ill) to institutions that demonstrate capability to step in.

Similarly, he sees new eased approaches to bail and defendant rights in court as "well intentioned" but problematic for policing and, consequently, making the city less safe. He would mandate development of a "color-blind" algorithm system for "safe" bail based on a suspect's arrest history, crimes committed on previous releases.

But Mr. Bratton remains the optimist. "With collaboration between cops and community," he concludes, "and with judicious leadership, a willingness to root out both bias and the biased, and a refusal to tolerate either brutality or aggression, we can recognize each other's humanity — we can see each other."

Bill Bratton lives in Hampton Bays.

David M. Alpern hosted the "Newsweek on Air" and "For Your Ears Only" radio broadcasts for more than 30 years, now lives in Sag Harbor, and hosts live and Zoom programs for local libraries, most recently a conversation with Kati Marton about "The Chancellor," her biography of Angela Merkel, on the YouTube channel of the Hampton Library in Bridgehampton.