Robin Dellabough thought she would age into her 70s quietly, no surprises. But when a friend of hers tried out 23andMe, the genealogy biotechnology, and raved that she should do the same, she thought to herself, "What do I have to lose?"

Ms. Dellabough, a Westchester County poet with a history of visiting Amagansett, knew she was different, but could never quite see the full picture. For one thing, she looked different from her four younger siblings — brunette and standing a modest 5-foot-2, while the others were willowy. She also kept her nose buried in books; the others were athletes.

She grew up in an essentially WASPy household, but she felt more connected to her Jewish friends and their families. She often had dreams of blurred faces in train windows and was convinced that somehow in a past life she had been Jewish.

It didn't take long for the genealogy results to come back: She was 50-percent Jewish. "I knew it!" she exclaimed, and bragged about the results to her siblings and children.

But reality sank in when they realized that this news meant that one of their parents, who had already died, must have been Jewish. The question was, who? She urged her siblings to also submit their DNA to 23andMe, but they discovered that none of them were Ashkenazi — only she was.

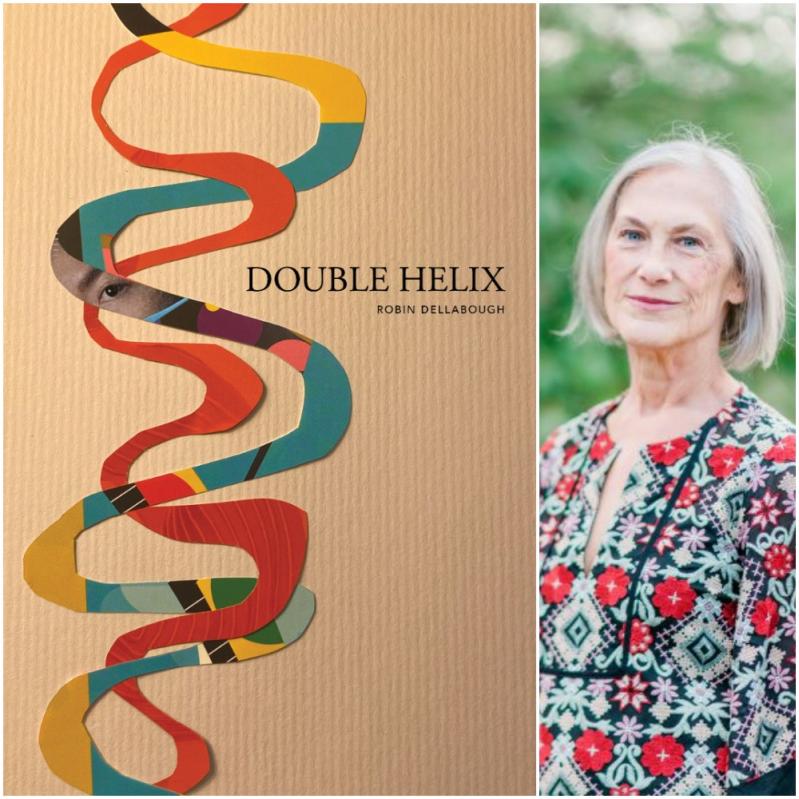

What started as curiosity evolved into a woman's search to discover her past, decades into life. Ms. Dellabough's autobiographical book of poetry, "Double Helix," out last month (Finishing Line Press, $19.99), poses questions around marriage and identity. She reckons with the reality that the father who raised her was not her "true father." Instead, her biological father, or "first father," as she calls him, was a Jewish man named Norman Peterzell.

A graduate of the University of California at Berkeley's Graduate School of Journalism, she used her research skills and found that Mr. Peterzell, who, like her parents, had died, apparently looked a lot like her. She managed to connect with his children — her half siblings — who showed her photos.

She had spent her adult years weaving through creative jobs, including ghostwriting and editing books, but poetry was a pastime she enjoyed privately. One day it dawned on her that she had always put her writing on the back burner, so at age 66 she put pen to paper. After several years of crafting her poems, they became a book.

Ms. Dellabough, who is now 70, spent a good portion of her marriage, dating back to the 1990s, vacationing in Amagansett. In one poem, she reflects on often finding herself at the ocean's edge.

"First Night in Amagansett"

We find our way to the ocean's dark edge.

I shine a flashlight straight up,

a beam to make a path in sky.

He says Don't do that,

you could blind a pilot.

I laugh. Surrounded by amber

moon sliver, glowing white wave

crests, evocative bonfire, how

could anyone be blind?

But I don't see the two

shooting stars that fall

across his field of

vision.

In her poetry, Ms. Dellabough chronicles more than identity. She explores the rocky road of a 30-year marriage. Her poems tug at the strings of her broken relationship and the aches of parenthood. She doesn't stray from using profanities when she clearly couldn't find the right words. In one poem, she and her husband are out on a summer night in Amagansett, staring through binoculars at the night sky.

"Last Days in Amagansett"

The past was sometimes

tense with yearning for our

future:

We'd swim close

to each other,

never too far

from shore.

We'd see everyone

else we loved

standing on their

own.

We were safe and free

together in our watery garden,

grown out of

tears and

kisses we can't

take back.

Anabel Sosa, a former reporter for The Star, is a graduate student at the University of California at Berkeley.