“Shy”

Mary Rodgers and Jesse Green

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $35

Why "Shy"?

It's clearly not the tone set by a beaming book jacket photo and contradictory subtitle: "Alarmingly Outspoken."

And quickly we find just how far from reticent the late Mary Rodgers was about her feelings, fancies, behavior, and misbehavior as the daughter of the rich (but not overly generous) and famous Broadway and Hollywood composer Richard Rodgers and his wife, Dorothy, a published author, decorator, inventor, and classic beauty.

Both seemed disturbingly distant to her — "Daddy," she felt, most in love with his music (though with more than just an eye for other ladies), "Mummy" most in love with herself, but not unaware of her husband's nonmusical proclivities.

The state of their marriage, we are told, may be indicated by the story, "probably apocryphal," that when he couldn't find where to insert the ignition key in a new sports car, she cracked: "If it had hair around it, you'd find it."

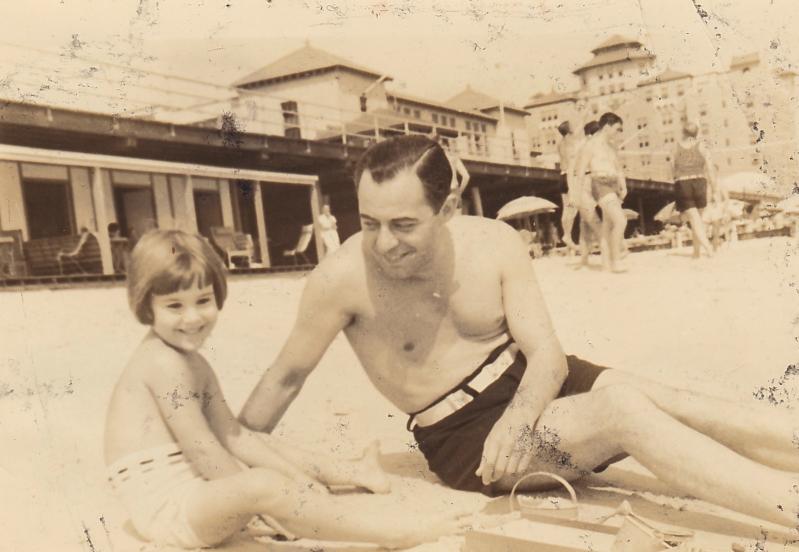

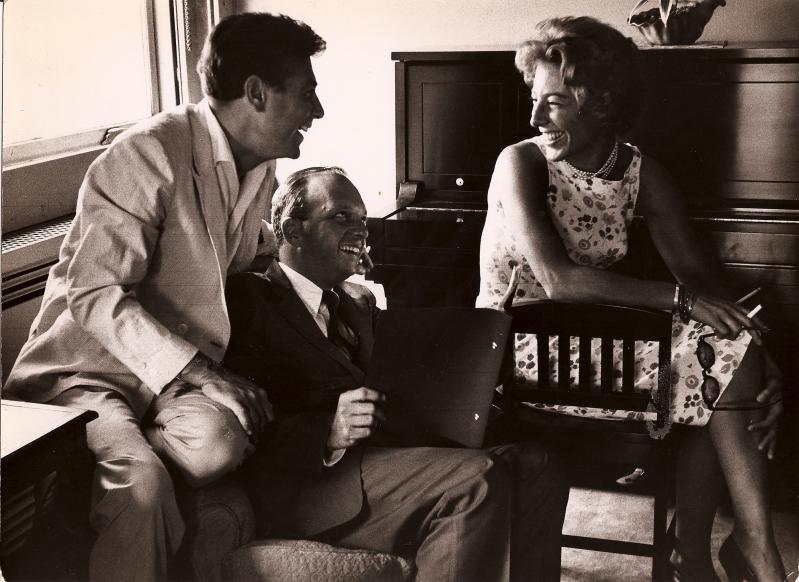

Photos Courtesy of the Rodgers-Beaty-Guettel Family

And so it goes in this snarky, often ribald, always revealing memoir — a dynamic dialogue between main text and footnotes that confirm, correct, contextualize, or downright disagree — created after years of freewheeling conversation with Mary by her co-author, the New York Times theater critic Jesse Green.

Early on we learn that young Mary fancied that the humanist lyricist Oscar (Ockie) Hammerstein would be a better dad. Yet she favored (as do I) Rodgers's first musical collaboration with tiny, troubled Lorenz (Larry) Hart ("Manhattan," "My Romance," "Blue Moon"), who actually joined Dick and Dorothy on their honeymoon in Italy and a London hotel. "It drove Mummy crazy."

Later a composer herself, Mary writes of Hammerstein, "all those goddamn praying larks and uplifting hymns for contralto ladies. I sometimes hated what he got up to."

In fact, "Shy" is the best-known song from Mary's one Broadway hit, widely revived, "Once Upon a Mattress," based on "The Princess and Pea," in which a king's husband-hungry daughter (with whom Mary admits she related) boisterously proclaims to be secretly demure. Carol Burnett originated the Mermanesque number.

And, indeed, Mary's naughtiness as child and adult may be seen as overcompensation for early years spent overweight and underconfident in an environment of super-achieving family and showbiz associates who for years made her feel she had to accept almost any offer — professional or personal.

So, when asked, and to earn income of her own, she wrote children's songs and children's books ("Freaky Friday" became a surprise hit in print and on screen) and scores for shows not born for Broadway fame, or not born at all. She boasts of tearing up any tune people said sounded like her dad.

She was, of course, later a director of the Rodgers and Hammerstein Organization, of ASCAP (the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers), and on various nonprofit boards, though not always comfortable as a Jewish woman among the male WASP high and mighty.

Still, she found moments to enjoy, at least in retrospect. On the alumnae board search for a new head of the eminent Brearley School, Mary recalls, "who should come before us but Jean Harris, wearing, yes, little white gloves. I just knew she'd kill a diet doctor someday."

As chairwoman of the Juilliard School, Mary was "the moving force behind the most sweeping changes the school would experience . . . until she resigned," the playwright Marsha Norman maintains. Later a plaque with Mary's name on it was attached to something somewhere there. "A water fountain?" Mary wonders. "I don't care. Meanwhile Juilliard doesn't have a musical theater division . . . just ridiculous."

As her first marriage soured, then ended, and already the mom of three, bed perhaps too often seemed the proper (or improper) way to repay a swell dinner. "A woman who tried everything," she calls herself. "I still thought I had to sing for my supper."

And she names names of some showbiz notables so repaid or repulsed. The songwriter Jule Styne "just came at me." Mitch Miller of Columbia Records was "a world-class lecher." More warmly remembered: the lyricist Sheldon Harnick, the stage/screen writer Leslie Stevens ("The Outer Limits"), and the producer Harold Prince (off-and-on over the years).

A leitmotif is Mary's not quite unrequited passion for the late Stephen Sondheim, a Hammerstein disciple, from the time they played games together as kids through adult friendship to musical collaboration including, perhaps most hilariously, a Jobim parody titled "The Boy From" ("Tacarembo la Tumba del Fuego Santa Malipas Zacatecas la Junta del Sol y Cruz").

There was even talk of a trial marriage — after her "shit-or-get-off-the-pot" letter to him — but only a period of regular overnights in the bed of Sondheim's new Manhattan townhouse (next to Katharine Hepburn's), with both of them too paralyzed for more than sleep. Yet she felt that he felt that no other man was good enough for her.

Not that she couldn't enjoy good sex with other gay men who were willing and able. "There are myriad ways to skin that cat," she assures us, adding: "After all, gay guys being warmer, more accessible, more tolerant and more emotional, listen to you." Among her favorites, her lyricist collaborator Marshall Barer ("Shy," "On Such a Night as This," "Beyond Compare"), when he wasn't overdoing drink or drugs.

One exception, she admits: Arthur Laurents, "the little shit" book writer for "West Side Story," "Gypsy," "The Way We Were." Also her first husband, the more closeted, uptight, eventually abusive Princeton grad and attorney Julian B. Beaty Jr., before they divorced and he went his own way in Bridgehampton.

On Long Island, liberal Mary stayed farther west, among the unlike-minded she dubbed "Quoglodytes."

In Sag Harbor she felt admiration for the gay playwright Larry Kramer during dinner before he spoke about his AIDS activism at Bay Street Theater, but afterward was shocked when he lambasted her for rising to ask "What can we do?"

"When you have all that money, why are you asking what can you do?" Kramer screamed.

"The strange truth is, I agreed with him," Mary recalls. "I hadn't done enough. And his tantrum came to seem almost noble to me."

About her second husband, the late film and theater executive Henry (Hank) Guettel, with whom she lived for 52 years and had three more children (one died at age 3), Mary makes no mention of gay appeal.

Through both marriages, she confesses loving pregnancy even more than writing music but also admits that music as a career distracted her too much from the kids that resulted. Still, she felt they "wound up good people, despite my time away."

Presciently, she told a tennis pal of mine that the newborn she gave him to hold would come a lot closer to her dad's musical genius than she ever did. And so Adam Guettel has — with two Tony Awards, so far, for "Light in the Piazza," and numerous other credits.

That Mary combined both motherhood and careers made her a modern feminist in fact if not in rhetoric or women's lib associations. "I am ashamed to admit that I found performative feminism too often unconvincing," she says.

"I didn't think of myself as having been kept down by the patriarchy — even by my own patriarch . . . unpleasable as he was," she explains. "He would have been just as disappointed in me if I had been a boy."

She also is ashamed for turning "so selfish and complainy" in her own final days, "disapproving and angry, as if I'd been cheated," though half a page earlier she has declared herself "perfectly comfortable with what I've accomplished."

But the Mary we come to know is still there at the end. "You have to face the facts. This may be the last time we see each other. You cry so easily!" she admonishes her co-author at their final meeting. "Just please don't make it dull like Mummy's and Daddy's. Include everything except what we can't. Otherwise, what's the point? We all fuck up and eventually putrefy, but at least I had fun. And didn't you?"

In their collaboration, Mr. Green agrees he did, then quotes Mary's reaction to the very first draft pages of this unique memoir, the only section she lived to read: "Make it funnier. Make it meaner." She would be well pleased.

Mary Rodgers died in 2014 at age 83. Jesse Green, student actor, later Broadway gofer, now Times theater critic, visited and swam at her house in Quogue with his husband and two sons. Their book will be out on Aug. 9.

David M. Alpern met Mary once at WNYC, one of the radio stations that carried the weekend "Newsweek on Air" broadcast, later the independent "For Your Ears Only," that he anchored for 30 years. Now retired, he hosts presentations for local libraries, live and by Zoom from his home in Sag Harbor.