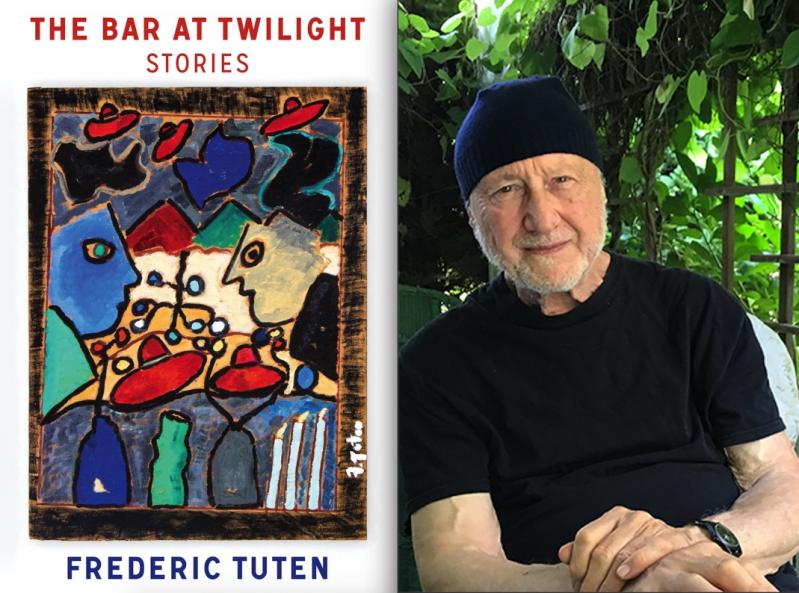

“The Bar at Twilight”

Frederic Tuten

Bellevue Literary Press, $17.99

The lives of artists; beautiful, complicated women; heartbreak, and the consolation of great art are some of the subjects in Frederic Tuten's new story collection, "The Bar at Twilight."

It is perhaps the most hackneyed literary analogy, and almost always incorrect, when writers are compared to Ernest Hemingway. But here we go again: There is a direct through-line from Hemingway to Frederic Tuten's stories. You see it in the prose, which tends toward the crisp and lean, in the romantic European settings, and of course in the obsession with painting: Poussin, Rousseau, and Hemingway's favorite, Cezanne.

Though the places change — Rome, Deauville, Paris, the East Village — the situation is often the same. The narrator, who is almost certainly a stand-in for Mr. Tuten himself, is in a glamorous place at the end of a relationship. There are no tears; the narrator is resigned to the end, as if it were simply the cycle of things. The consolation, again and again, is art — the interacting with or making of it.

In "The Tower," a woman announces she is moving out of the apartment she shares with the narrator. He is a little stunned but not entirely surprised (and maybe not entirely disappointed). Where will he find comfort? "The house seemed full now that she had gone, the rooms packed with me. I wandered about, savoring the quiet, the solitude, the way my books, sleeping on their shelves, seemed to glow as I passed by — old friends who no longer need share me with another. . . . Maybe I would sit all day and read."

Eventually the woman's lover shows up at his apartment looking for her. The narrator observes him. "I noticed he wore burgundy moccasins with tassels and was without socks. That he had an orange suntan that glowed." This is his woman's new lover? The narrator will be just fine without her.

In "The Veranda" a wealthy widower remembers her third husband ("the love of her life") from her seaside mansion in Montauk. The husband was a painter, "not famous but not unrecognized," also remote and highly intellectual. Perhaps not surprisingly, he tends to favor women based on their literary taste. "He liked women who read books he honored."

Their courtship begins at a museum, as he follows her into a few rooms to observe her taste in painters. Eventually he approaches her in the cafe. "Look . . . I understand your interest in the connection between Poussin and Picasso, but I don't see your leap to Parmigianino, a fine artist but irrelevant to what connects the other two." Not a first line I've ever used, but it seems to set the stage.

Later, when she is divorced, she buys a few of his watercolors and they become lovers. They remain so for many years, until he is drowned off the coast of Montauk. Or was it a suicide? There is ambiguity enough to speculate.

"Winter, 1965" is one of the best stories I've encountered about the loneliness and disappointment of being a young "yet unpublished" writer. As it opens, a budding novelist has been told that his story will appear in the next issue of Partisan Review (for perspective, this might be akin today to a young director being told his film has been accepted at Sundance). He has even announced it to everyone at the literary bar where he drinks.

But when he buys the Review the day the issue appears, his story is not included. The disappointment is stunning, incomprehensible. Inquiries to the editor go unanswered. He is nobody, they have simply changed their mind. He returns to his deadening day job. There is no lover. He eats dinner by himself. A monk without hope.

And yet the story is subtly exultant. An attractive girl comes to his apartment, a junior editor at the Review. They go out for tea. She has no answer as to why his work is not being published; she simply liked the story and wanted to meet him. At the end of the night she makes sure to tell him she has no boyfriend. And after a day or two of despair, he wakes up again early before work. The final line reads, "He rose and went to the kitchen table and to the gleaming red Olivetti waiting for him there." Refusing to fail, he will, we are sure, triumph.

Not everything here works. "L'Odyssee" makes awkward analogy to both Joyce and Homer, and there is a sameness to some of the cafe talk in some of the stories, as if Mr. Tuten were trying endlessly to rework Hemingway's classic stories "A Clean, Well-Lighted Place" and "Hills Like White Elephants."

But what a relief it is to encounter contemporary fiction that does not beat the drum of political will or social justice. As Mr. Tuten himself states in "The Veranda," "Beauty was the end and reason for all art, period."

With stories like "Winter, 1965" and "The Veranda," which are near classics, Mr. Tuten reaches that benchmark in "The Bar at Twilight," and solidifies his reputation as a distinctive, if overlooked, practitioner of literary art. In the story "Lives of the Artists," a character states, "Years ago, a famous artist blessed with late recognition told me, 'Stay in line long enough and eventually you will be served.' "

May such a fate await Frederic Tuten.

Kurt Wenzel's novels include "Lit Life." He lives in Springs.

Frederic Tuten, who lives in Southampton, will discuss "The Bar at Twilight" with the novelist Iris Smyles at the East Hampton Library on July 12 at 6 p.m.