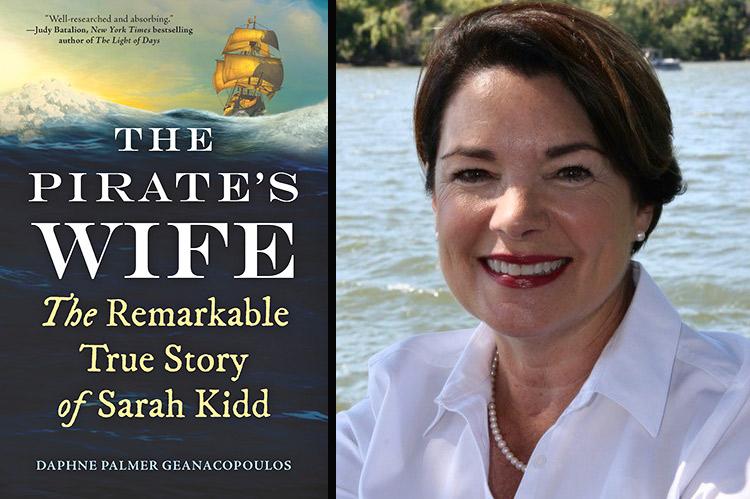

“The Pirate’s Wife”

Daphne Palmer Geanacopoulos

Hanover Square Press, $27.99

Daphne Palmer Geanacopoulos has done an admirable job of rescuing Sarah Kidd from history's crowded attic of forgotten figures. "The Pirate's Wife" presents an intelligent, courageous, and resourceful woman living life to the fullest in colonial New York despite numerous injustices imposed by English law and male authorities.

Much of the injustice Sarah faced revolved around property, such as her substantial silver collection, valuable furnishings, and well-located real estate where she lived and ran a successful shop in the late 1680s (water views from Pearl Street and the future Wall Street). Those material things came to the young woman born Sarah Bradley well before she first laid eyes on Capt. William Kidd, a wealthy man himself and a newcomer to New York.

It was property — a real estate transaction — that caused them to meet shortly after the death of Sarah's first husband, William Cox, a flour merchant she had married at the age of 15 after an Atlantic crossing with her widowed father and two younger brothers.

But under English law, Sarah did not own what she had because she was property herself, the property of her husband. This doctrine — which lingered for another 200 years — meant gross unfairness in Sarah's case as she had acquired many of her things through her work as an importer and merchant. Cox had enabled this enterprise out of an understanding of his wife's business savvy and talent for choosing clothes and other merchandise that appealed to patrons as far away as Boston.

When Sarah met Kidd, in 1690, Cox had died in an accident, her shop had been closed, and local authorities were interfering with her ability to maintain the life she had known.

While Kidd sailed off to the Caribbean, Sarah took a second husband, John Oort, believing it would help her re-establish herself. It didn't. He died suddenly, and the authorities would again act unfairly, imposing a hefty fine for Sarah's failure to exhibit Oort's things as part of the processing of his estate. Her lapse may have been an act of civil disobedience, for "his" things were really her things. Oort had turned out to be a financial failure.

Sarah bounced back. By the time the fine was levied, she enjoyed the support of a new husband, the one she married for love. Having returned from the Caribbean, William Kidd reacquainted himself with Sarah and the two were married in September 1691. She was 21. Kidd was 37. Such were colonial times that they attended a public hanging on the morning of their wedding day.

If Sarah thought life was unpredictable before she met Kidd, the ups and downs only increased after she became his spouse. First came a nesting period, with children and community support, for Kidd was charismatic as well as popular, having helped oust a despotic local official. Eventually, Kidd's wanderlust took hold and Sarah's world changed again after her husband sailed to Africa with a new commission to act as a privateer — a lawful way, in the eyes of the English, to plunder French ships.

What happened next is somewhat in dispute, but under any scenario it's a wild ride, well told by Ms. Geanacopoulos. Did Kidd turn rogue after a couple of "legitimate" raids, or was he the victim of a mutinous crew? Whatever the truth, Kidd returned with loot worth as much as $88 million at today's values. As the author writes, the bounty included "sixty pounds weight of gold, about one hundred weight of silver, and seventeen bales of East India goods. . . . And there was more on a ship hidden in Hispaniola."

Many on the East End have heard the story that some of Kidd's treasure is buried on Long Island. Is the fabled place in Setauket, Hempstead Harbor, or the sandy soils around Montauk's Money Pond, said to be so named because of the treasure? Nelson DeMille's "Plum Island" offers another location. "The Pirate's Wife" adds much well-researched and fascinating information to these snippets of lore, broadening one's understanding of Kidd and showing that colonial authorities' duplicity, pursuit of self-interest, and cruelty were not limited to female targets.

On his way to Boston to seek a pardon from one such official, Lord Bellomont, Kidd anchors off Block Island, a haven for ex-pirates. He sails back to Gardiner's Island, where John Gardiner, the third generation of his family to inhabit the island, makes a thoroughly enjoyable cameo appearance. Known to be helpful to mariners, Gardiner supplies Kidd with sheep and hard cider for a reunion feast with Sarah and their children, and Gardiner allows Kidd to dig a hole on his 3,300 acres to store some treasure. It won't stay there for long.

Ms. Geanacopoulos also deals with an assertion of property rights far more problematic than a pirate's booty of coins and silks: enslaved people taken from Madagascar and elsewhere. In the late 1600s, she reports, the enslaved represented as much as 20 percent of New York's population. On the East End, where we take for granted pleasant traces of the English, such as cape-style homes, wainscoting, and place names like "Hampton" and "Maidstone," it is important to be reminded of the full scope of coastal New York's early English settlements. Their legacy is also one of terrible inequality.

The first major book on pirates, published during Sarah's lifetime, made no mention of her. Ms. Geanacopoulos has done right to correct that slight. One does wish that Sarah, in addition to her other accomplishments, had learned to write more than her initials, for there is little documentation of her emotions, no handwritten letters, no journal entries. Ms. Geanacopoulos fills that void using writerly formulations such as "she may have felt" or "it must have seemed." While this technique could have been used more sparingly, the author's inferences often ring true, especially in one area: Sarah's zeal to protect those she loved.

For too short a time, from Sarah's perspective, William Kidd was one of those people.

Marian E. Lindberg is the author of "Scandal on Plum Island: A Commander Becomes the Accused" and "The End of the Rainy Season: Discovering My Family's Hidden Past in Brazil." She lives in Wainscott.