“Lou Reed: The King of New York”

Will Hermes

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $35

Ten years after his death, Lou Reed remains a unique figure in rock-and-roll and, as the subtitle of the latest biography implies, a personification of New York City in the latter half of the 20th century and beyond.

Late in life, Reed owned a house in Springs with his wife, the artist Laurie Anderson, and along with the hamlet's claim to many an essential visual artist, history will record that Springs is where Reed left his body, eyes wide open, hands doing tai chi, according to Ms. Anderson.

The end of Reed's earthly journey was of course preceded by 71 years of oftentimes complicated, sometimes scandalous living, all of it unsparingly detailed in Will Hermes's deeply researched "Lou Reed: The King of New York." Over more than 440 pages, Mr. Hermes, himself a New York native and a regular contributor to Rolling Stone magazine and National Public Radio's "All Things Considered," is nonjudgmental in chronicling Reed's audacious attitude toward seemingly everything, not least the artist's prodigious indulgence in drugs, ambisexual behavior, and, above all, perseverance through critical and commercial disappointment.

A founder of the short-lived and star-crossed New York art-rockers the Velvet Underground, Reed will forever be known to the masses for a handful of songs: "Walk on the Wild Side," "Sweet Jane," "Heroin," and "Perfect Day" among them. But his output was immense. In Mr. Hermes's biography, the reader learns how the artist's upbringing in Freeport, his time at New York University and Syracuse University, and associations with the poet Delmore Schwartz, the pop artist Andy Warhol, and champions including David Bowie, the critic Lester Bangs, and music-business executives shaped his artistic sensibility. For true fans, "Lou Reed" is an essential companion to the music.

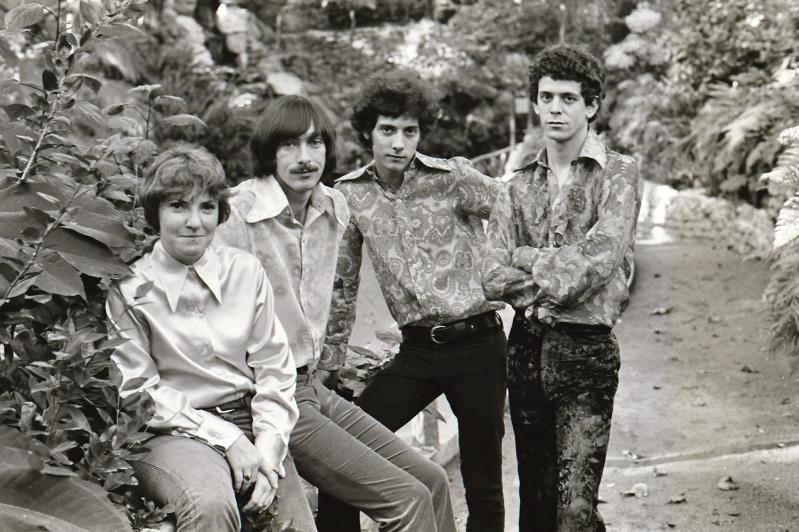

Courtesy of M.C. Kostek/Velvet Underground Appreciation Society

All of the influences, seemingly, are detailed: the emotionally distant father, born Sidney Rabinowitz, the early years in midcentury suburbia ("the most boring place on earth," Reed would later describe it), regular beatings in junior high school, Fats Domino and 1950s doo-wop, and an emerging sense of queerness. "How much Reed's sense of otherness fueled his creative desire is an open question," Mr. Hermes writes. "But his sister had no doubt that 'his hyperfocus on the things he liked led him to music.' "

Along with the burgeoning rock-and-roll scene of the early 1960s, a free-jazz performance by the Ornette Coleman Quartet on Manhattan's Lower East Side made a profound impact. So did a 1960 emotional breakdown at N.Y.U. and the recommendation for electroshock therapy. "He made it into a source of strength," Mr. Hermes writes, "one that set him apart from the suburbs, his parents, and the sort of culture that would co-sign it."

Back at Syracuse, he co-founded a literary journal. Lenny Bruce and Federico Fellini's "La Dolce Vita" further shaped his awareness. So did heroin, which Reed first used in his early 20s, perhaps "in service of the sort of 'lived experience' Schwartz taught him was at the core of great literature" and through which he contracted hepatitis.

Post-graduation, Reed moved to New York, finding work as a songwriter for a small label, with more key events soon to follow: meeting the musicians John Cale and La Monte Young, and the artist Jonas Mekas. A determined Reed was in the middle of a fertile avant-garde scene punctuated by psychedelic drugs and "happenings," and with his new companions it was perhaps inevitable that the Velvet Underground would form, become an integral part of Max's Kansas City and Warhol's "Factory" workspace and "Exploding Plastic Inevitable" events that were reimagining and reinventing film and visual art, and, before very long, burn out amid personnel changes and creative differences.

The comprehensive story of Reed's life is the backdrop to his approach to music, and the public and critical reception to same. "The Velvet Underground might not have had a large following, but they had a devoted one," Mr. Hermes writes. In the early 1970s, Reed briefly put down the guitar and turned to poetry. That experience, and earlier turns with prose, dovetails with the "deadpan speak-singing" vocal delivery of so much of his work — one exception being 1975's bizarre and patently inaccessible "Metal Machine Music," an hour of feedback and nothing else.

Success and acclaim were inconsistent at best. Triumphs like "Walk on the Wild Side" (its lyrics introducing a cast of Factory regulars), "Perfect Day," and "Satellite of Love," all from his "Transformer" album, were followed by many more releases met with a lukewarm, or worse, reception. In The Village Voice, the "Berlin" album was called "a concept album of the highest order," but in Rolling Stone it was deemed among "certain records that are so patently offensive that one wishes to take some kind of physical vengeance" on the artist. One critic deemed 1976's "Rock and Roll Heart" "as painless and boring as modern dentistry." In "The Blue Mask," from 1982, "Reed had recorded a 'rock masterpiece,' " Mr. Hermes writes of its critical reception, "and once again, it would sell modestly, reaching number 169 on the pop charts before disappearing."

Reed eventually kicked his drug habit, a later generation of musicians would discover, revere, and cover the Velvet Underground's music, and the complicated artist's tenacity finally paid dividends, as did a willingness to license his best-known works for advertising, finally making him a wealthy and widely heralded man. Redemption also came in an uncharacteristically affectionate 1992 letter from his father. Relationships of many varieties came and went, and finally Reed met Ms. Anderson, "another New York City woman whom he found tremendously captivating, and with whom he had a great deal in common."

"Reed's public image began softening," Mr. Hermes writes, "and his new girlfriend seemed to be a big part of it." He collaborated with contemporary artists, took up photography and tai chi, and was even invited to the White House to perform at a state dinner with President Clinton and Vaclav Havel, the Czech president, poet, playwright, and onetime dissident.

But in time, his body finally rebelled against decades of abuse. The chronicle of his decline and death is painfully sad, and brings to mind a few lines from 1992's "What's Good (The Thesis)": "Life's like forever becoming / But life's forever dealing in hurt / Now life's like death without living / That's what life's like without you. . . . Life's good / But not fair at all."

For serious fans of Reed and the Velvet Underground, Mr. Hermes's biography is essential reading. The casual fan, too, will enjoy "Lou Reed: The King of New York," learning quite a bit about the myriad causes and conditions that created and drove this temperamental, complicated artist.