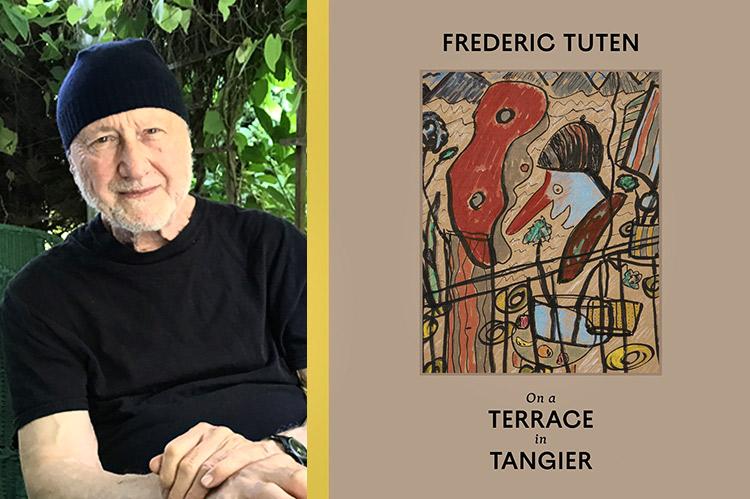

“On a Terrace in Tangier”

Frederic Tuten

Koenig Books/KMEC, $40

"I am a writer and artist. It's not this or that. It's this and that," asserts Frederic Tuten, a part-time Southampton resident known for his novels, essays on art, and wit.

The context is his latest volume, "On a Terrace in Tangier," in a conversation and interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist, the Swiss art curator. Their Q&A follows short prose vignettes and accompanying prints of pastels and ink on cardboard, testament to Mr. Tuten's talents in many fields. He starts each coupling with the visuals, he tells Mr. Obrist. Printed side by side, the writings and art illustrate each other in a whimsical way. Or, as he puts it, they collaborate in creating "a new dimension of feeling."

If you like whimsy, the result is joyful, even if the emotion is wistful. I like Mr. Tuten's whimsy; he enlivens the quotidian with a charming, worldly view. Day-to-day matters, such as breakfast, can occur on a terrace. Maybe that's what terraces are for, aside from being perfect platforms for vases, cups, and sombreros, recurring Tuten tropes.

The book begins with a terrace in Tuscany; it takes a while to get to the one in Tangier. These transits make for more than nice alliteration, introducing color and pattern. His images express human estrangement so viscerally. What, besides "our coffee, had fled to colder climes"? Wherever, we are far away, going or coming. That is, to and from places, and each other.

Take, for example, one piece titled "Cups in Flight": "Two cups of the several that had been resting on a cantina table decided after a long conversation with their fellow cups that they, like the sombreros they had seen flying overhead, also wished to take flight."

As you may imagine, the lonely saucers wanted to join the cups. "And off they went into the windy sky, hoping that one day they would catch up with the cups and the flying sombreros and become companions in adventure."

Facing the story, four cups, two seemingly caged and two on saucers in flight, frame a still life of objects — a candle, a vase, a striped cylinder — on terrace tables. Colors — blues, reds, greens, yellow — are muted by the brown cardboard backdrop, the palette of the art.

In "Tangier," the speaker observes the milieu in painterly strokes — a man rushing home, a baby goat draped over his shoulder, the crazy racket of sparrows in the jasmine trees. His "pot of tea, my cup packed with veined mint leaves and regrets." A wayward sea, steadfast mountains, "the sky harbored a crestfallen moon."

An unnamed she "was back in our hotel room, packing her bags, and not waiting for my return. The call to prayer broke the silence, and the air went still with uncertainty."

You can see the mountains, the sea, the cup, the terrace rails, and foliage in the picture. The cartoonish figure in a cap, his phallic schnoz red. Is he the speaker or the man bringing home dinner? The piece echoes the desire for connection, this time human.

Except when his objects talk, as in the three sombreros who wait on pegs at a cantina for their owners standing at the bar, "soaking in the tequila." One comes home every night drunk and beats his wife and kids, another shoots stray cats in his garden, and the third leaves his luxury cars at home, taking a bus to work, the better to molest young women on the way home. No wonder the three sombreros decide "to flee and live on their own in the windy skies." Pictured in blue, they look like flying saucers.

In "Sombrero Ballet," the wind provides the music for the wide-brim hats to spin in the sky after one's crown had been crushed at a performance of "Swan Lake." The sombrero "had not known that humans were capable of such grace and agile elegance. Once free in the hills, he taught other sombreros the rudiments of the ballet."

The enforced loneliness of the pandemic allowed for the freedom and time to create this work, some exhibited at Harper's in East Hampton in 2021.

The final section provides a philosophical discourse. As the two art experts, the author and Mr. Obrist, converse, they acknowledge that painters who write have existed through history. Mr. Tuten cites many examples, Henry Miller, D.H. Lawrence, Leonora Carrington, Djuna Barnes. In "The Musee des Beaux Art," he mentions the way we talk about W.H. Auden's take on Brueghel's "Landscape With the Fall of Icarus," usually explained by a view that tragedy often goes unnoticed. That's not important to him. He's not interested in a didactic interpretation of one to the other; rather, he sees his drawings and stories speaking to each other.

Given this goal, his process is simple. He starts with a border, a frame that is starved for image and color. He adds a line and puts things — jars, cups, candles, clouds, sombreros — above and below. Then he sees how the colors speak to one another: Do they rhyme? He wonders, should I make a plan? "I'm afraid I'll lose spontaneity. I don't want to make a well-made, slick, merely acceptable painting or drawing. . . . I'd rather fail."

Painter friends inspire him: Eric Fischl, Ross Bleckner, David Salle, Jennifer Bartlett, Roy Lichtenstein, and R.B. Kitaj among them. But poetry nourishes him. During lockdown he read Wallace Stevens, Elizabeth Bishop, and Tennyson.

Ultimately, word and image create a poetic language. Yes, we call sombreros who think, talk, and dance in the air personified, and we also call them fabulous.

Regina Weinreich, author of "Kerouac's Spontaneous Poetics," editor of "Kerouac's Book of Haikus," and co-producer/director of "Paul Bowles: The Complete Outsider," lives in Montauk and Manhattan, where she teaches courses in Beat literature and aesthetics at the School of Visual Arts.