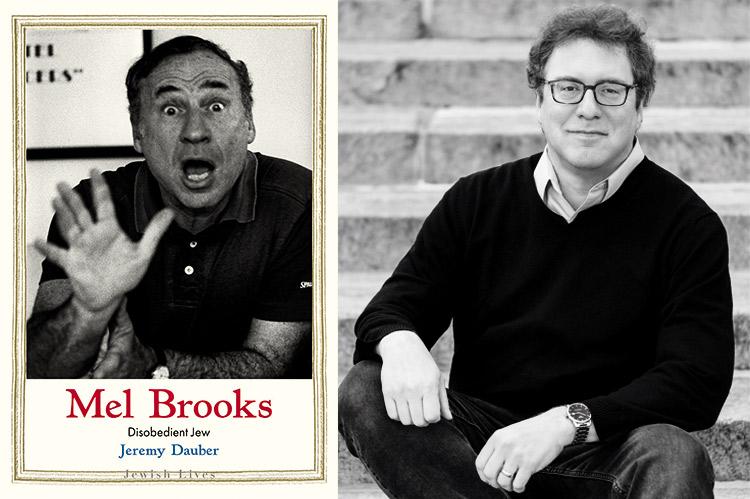

“Mel Brooks: Disobedient Jew”

Jeremy Dauber

Yale University Press, $26

The title of Jeremy Dauber's new book, "Mel Brooks: Disobedient Jew," has its genesis in a 1978 New Yorker profile by the English critic Kenneth Tynan.

"I take my leave. Brooks clicks his heels and bows, saying, 'Your obedient Jew.' He misses no opportunity to brandish his Jewishness, which he uses less as a weapon than a shield. Remember (he seems to be pleading) that I must be liked, because it is nowadays forbidden to dislike a Jew."

In this mini-biography, part of Jewish Lives Series from Yale University Press, Mr. Dauber is admirably restrained in his wielding of the antisemitic label, but here, rightly, he cannot help himself. "Tynan's old school-tie anti-Semitism is showing a bit here . . . he seems to have missed the point." Clearly Mr. Brooks, one of the great American satirists of the 20th century, was being ironic (and we wonder why Tynan, a giant among literary critics, can't see it).

"Brooks," Mr. Dauber reminds us, "was never, ever obedient."

He was born Melvin Kaminsky in 1926 on New York's Lower East Side — allegedly on the family kitchen table. A few years later his father, Max, died of tuberculosis, and Melvin and his three brothers were forced to spend part of the time at something called the Hebrew Orphan Asylum. Still, being the youngest, he was admittedly "adored." Mr. Dauber reports him saying, "I was always in the air, hurled up and kissed and thrown in the air again. Until I was six my feet didn't touch the ground."

If this isn't the childhood template for a comic genius, then such a paradigm does not exist.

After a move to Brooklyn, Melvin was hitting the streets, where jokes substituted for physical prowess. "Those Brooklyn streets were a classic training ground for the motor-mouthed Jewish kid, short in stature and long in sass, who'd rather use his wits and feet than his fists," writes Mr. Dauber.

Movies quickly became his obsession — he would sometimes stay in a darkened theater from 11:30 a.m. till the late evening. His tastes were disparate: He loved westerns, plus both the Marx and Ritz Brothers, and musicals, especially the Fred Astaire-Ginger Rogers series. ("Swing Time" he would later identify as his favorite movie of all time.) All of these genres, of course, would manifest themselves later in his career.

Mr. Dauber spends considerable time on Mr. Brooks's formative years. His stint as a Borscht Belt busboy and then tummler — a kind of master of ceremonies for the house entertainment. His infectious personality endeared him to no less than Sid Caesar — that king of 1950s comedy — who put him on the payroll and paved the way for a writing job on television's "Your Show of Shows."

When the series ended he tried his hand as a Broadway producer, resulting in at least two crushing flops. This began a fallow period in which he hit the creative skids, got divorced, and went heavily into debt. Still, he seemed to fail upward — the talent was too large to ignore.

By the mid-1960s he found himself in Hollywood with an accidental hit on his hands, creating the TV series "Get Smart" with Buck Henry. Reviews were mixed — criticisms of "tastelessness" would become familiar to him — but the show earned him and Henry an Emmy nomination, and for Mr. Brooks a much-needed success. "In its first year," Mr. Dauber reminds us, "it was the second-highest rated show on NBC, just behind 'Bonanza.' "

Movies, however, beckoned him. After fits and starts, he drew on his own Broadway failures and pulled together the landmark comedy "The Producers" with Gene Wilder and Zero Mostel. Mr. Dauber is at his best here, identifying the film's wholly unabashed Jewish sensibility. " 'The Producers,' in its own way, is about a Jewish family," he keenly observes. About Bialystock — the name of Mostel's character — he says it "is not only reminiscent of the alt-bagel you could pick up at Zabar's after a matinee, but is also a central Jewish city in Eastern Europe."

The script revolves around the farcical musical "Springtime for Hitler," which spawned a controversy about whether comedy could include jokes about Nazis. Mr. Brooks's defense has become a kind of aphorism of its own: "I think you can bring down totalitarian governments faster by using ridicule than you can with invective."

A few years later came "Blazing Saddles." One of the movie's contributors was Richard Pryor, who apparently offered the other writers cocaine on the first day of work ("Never before noon," Mr. Brooks responded). Mr. Dauber rightly laments Warner Brothers' decision to refuse Pryor as the lead actor. "Pryor's volcanic talent, his ability to create comedy based on simmering and seething anger, would have taken the movie in a very different direction. . . ."

Instead Cleavon Little took the role, the actor eschewing anger for a "detached and sardonic amusement," which, Mr. Dauber argues, was "more congruent with a Jewish response." Either way, "Blazing Saddles" became one of the top-grossing movies of the year, and solidified Mr. Brooks's career as a writer-director.

"Young Frankenstein," his 1974 masterpiece, is duly praised by Mr. Dauber, though its assessment seems oddly brief compared to "The Producers" and "Blazing Saddles." The author does take time for a bit of overreach, however, as he tries to turn this manic satire of horror films into an allegory of Jewish identity. For this he cites the insistence of Wilder's Dr. Frankenstein to have his name pronounced "FrONKensteen." As if to convince himself, Mr. Dauber writes, "How can a movie not be about acculturation when much of its triumphalism comes in accepting your original name, unchanged, from the old country?"

"Young Frankenstein" was the zenith of Mr. Brooks's film career, and from here Mr. Dauber's biography grows slightly schematic. Admittedly there is a downward trajectory to the quality of the films — what can one say about embarrassments like "Fatso" or "Dracula: Dead and Loving It"? But this coincides with a dearth of biographical material. We learn little, for example, about his marriage to Anne Bancroft — Successful? We are left to assume so — and next to nothing about his family life, including his precocious son Max, who wrote the book "World War Z" and is a frequent guest on Bill Maher's "Real Time."

Still, though slightly misshapen, there's a lot packed into this biography. Mr. Dauber is clearly an avid historian of Jewish comedy, and almost all his observations land, as with his assessment of Mr. Brooks and Woody Allen: He implies that it stung Mr. Brooks that Woody was appreciated by the "smarties" while he himself was more of a conventional crowd-pleaser. This, he suggests, was the impetus for Mr. Brooks to form his own production company, releasing films such as David Lynch's "The Elephant Man" and "84 Charing Cross Road."

And all the greatest hits are here. It is the very mark of a comic genius that, for those old enough to remember, we still recall the great gags. "The 2000 Year Old Man"; the flatulence scene in "Blazing Saddles"; the musical parodies "Springtime for Hitler," "The Inquisition," and "Puttin' on the Ritz"; the Star of David-shaped craft of "Jews in Space" ("They're going to protect the Hebrew race!"), and "It's good to be the king!" from "History of the World," among others.

Finally there's the bittersweet success of the Broadway version of "The Producers," which finally gave Mr. Brooks the stage hit that eluded him decades before.

Why are Jews funny? Mr. Dauber asks this at one point, and his answer is both familiar and poignant: "There's no question that Jews, thanks to the vicissitudes of diaspora history, have long been peculiarly and particularly positioned to examine the structures, conventions, and foibles of a particular society and culture that they are only partially of, and then try to poke at them."

This is, of course, the legacy of Mel Brooks. And Jeremy Dauber's brief but punchy biography reminds us why he should be on the list of major American artists.

Kurt Wenzel, a novelist and frequent book reviewer for The Star, lives in Springs.

Mel Brooks formerly had a second home in Southampton with Anne Bancroft.