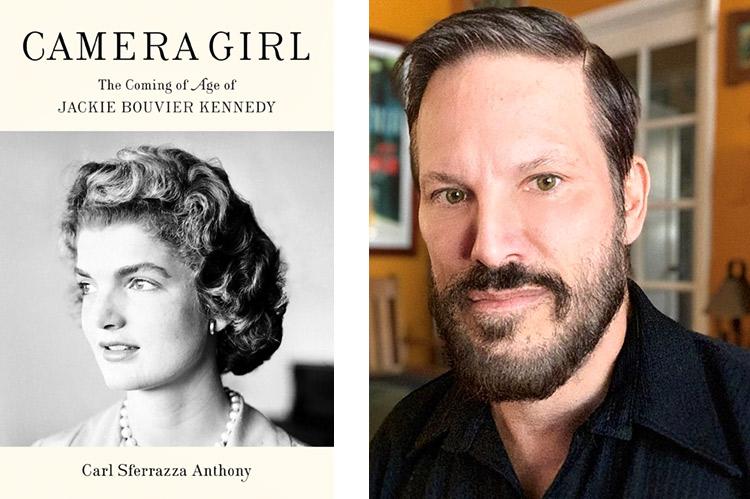

“Camera Girl”

Carl Sferrazza Anthony

Gallery Books, $29.99

Eight years to the day before she sat in the front row on a platform outside the east side of the Capitol in Washington, D.C., watching her husband take the oath of office to become the 35th president of the United States, an as-yet-unmarried Jacqueline Lee Bouvier found herself at the first inauguration of the 34th president, Dwight D. Eisenhower, camera around her neck and notepad in hand.

Bouvier, still unknown throughout the world, was about to write her first bylined article for The Washington Times-Herald, a conservative newspaper that published 10 editions a day between 1939 and 1954. (She was there to interview people at the inauguration parade.) During the two years she worked at the paper, most of her time was spent compiling a daily "inquiring photographer" column that covered a broad range of topics, from the frivolous to the weighty.

That job provides the title of "Camera Girl: The Coming of Age of Jackie Bouvier Kennedy" by Carl Sferrazza Anthony. Mr. Anthony has written 10 previous books on first ladies, two of them about Jacqueline Kennedy and the Kennedy White House.

Though the word is grossly overused, Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis was undeniably an international icon, one of the best-known and most admired women of the 20th century. When it comes to icons, we tend to believe we know everything about them and almost think of them as personal acquaintances. This 379-page book, which includes nearly 90 pages of notes, demonstrates the extent to which that is not the case. The preponderance of what Mr. Anthony shares with us is new information — carefully researched and clearly presented — outside of the "Jackie canon." The 16 pages of well-captioned photos are a valuable supplement to the text.

While it is widely known that Jacqueline Bouvier was born on July 28, 1929, in Southampton (and brought home from the hospital to a house her parents had rented in East Hampton), a great deal less is known about her life between then and her marriage to John F. Kennedy shortly after her 24th birthday. Frankly, it's not a particularly pleasant story.

Neither of Jackie's parents was a paradigm of sterling character. Her father, John Vernou Bouvier III ("Black Jack"), was what used to be called a "cad." He was handsome, he was a successful Wall Street broker (until he wasn't), he had a lot of money (until he didn't), he drank excessively, and he was a serial womanizer (sailing to Europe on his honeymoon, he attempted to pursue the famously wealthy heiress Doris Duke). Some years later, it was he who told his daughter that "men are rats."

Janet Norton Lee, 17 years younger than Jackie's father, is first described as "an eager social climber." Her grandparents were poor Irish immigrants, though she concocted a family origin story that substituted English aristocrats. Janet was attractive, domineering, and arguably shallow.

The marriage that produced Jackie and her sister Lee (who is mentioned only rarely in the book) was not a good one and ended in divorce when Jackie was 10. From that point forward, not only did her parents show nothing but contempt for each other, but they also seized every opportunity to use their daughter as a pawn in their endless battle.

The future first lady's adolescence was spent shuttling between the homes of her mother and stepfather (Hugh D. Auchincloss) in McLean, Va., and Newport, R.I., and her father's residences in Manhattan and East Hampton. The Bouvier addresses here were first an estate called Lasata, at 121 Further Lane, and later a rented cottage at the Sea Spray Inn, adjacent to Main Beach. (An entire chapter of the book is titled "East Hampton.")

Highly intelligent, as well as clever and creative, Jackie was admitted to Vassar College, which she attended for two years. Though she earned excellent grades at the Seven Sisters school, she was bored and felt unstimulated by traditional courses. She spent every weekend she could in Manhattan, which exasperated her mother because it meant more time spent with her father. Though there are competing stories about why she was expelled from Vassar, the likeliest explanation is that she enrolled in a Smith College junior year abroad program in Paris without obtaining Vassar's consent.

Most significantly, that year in Paris turned Jacqueline Bouvier into a Francophile for life. Returning to the U.S., she finished her degree at George Washington University, majoring in French literature. Eager to return to the French capital, she entered Vogue magazine's Prix de Paris contest, which allowed the winners to work for six months in the Vogue offices in New York and another six months covering the world of haute couture in Paris.

After several grueling rounds of writing essays and creating portfolios, Jackie Bouvier won. Her mother objected to her accepting the prize, however, because of the half year it would keep her in Manhattan, close to her father's influence. An argument ensued, but Jackie ultimately bowed to her mother's will and turned down the prize. The future first lady did retaliate, by sending her mother a box containing a dead snake.

John F. Kennedy Presidential Library

That is when her stepfather, the well-connected Auchincloss, machinated to get her a job at The Times-Herald. Her roughly 600 "Inquiring Camera Girl" columns featured photos of, and responses from, nearly 2,600 people, both famous and obscure. Her daily column became quite popular.

One way to read this book is to follow the many subjects she chose. Some were trivial ("Why do you think people crack corny jokes in elevators?"), but many reflected what was on her mind at the time. One day, not long after casually meeting the charismatic Jack Kennedy, a first-term Senator from Massachusetts, at a Washington dinner party, the inquiry was "Should a girl pass up sound matrimonial prospects to wait for her ideal man?"

The most illuminating part of the book, in my opinion, is the account of how that casual encounter ultimately led to an engagement to be married. Suffice it to say, romance had little if anything to do with it. At a cocktail party in early 1953, a close male friend of the senator's took the young photojournalist aside and made it clear that Kennedy had known and been with a great many women, a pattern that would undoubtedly continue after he married. For her part, based upon her own family experience, Jackie exhibited no hesitation to countenance such behavior.

In fact, several other elements of the story of Jackie Bouvier's young adulthood would also be reflected later in her life: marrying for money and social position, considerable skill as a writer (and editor), fondness for France and all things French, and perhaps above all, her steadfastly remaining a strong individualist.

Counseling a young friend at school, Jackie Bouvier shared her personal philosophy of how life should be lived. "Become distinct," she said. As "Camera Girl" amply illustrates, by the time she was a young adult, the future Jackie Kennedy was already adhering to that credo.

Jim Lader, who owned a weekend home in East Hampton for many years, has reviewed books for The Star since 2009.