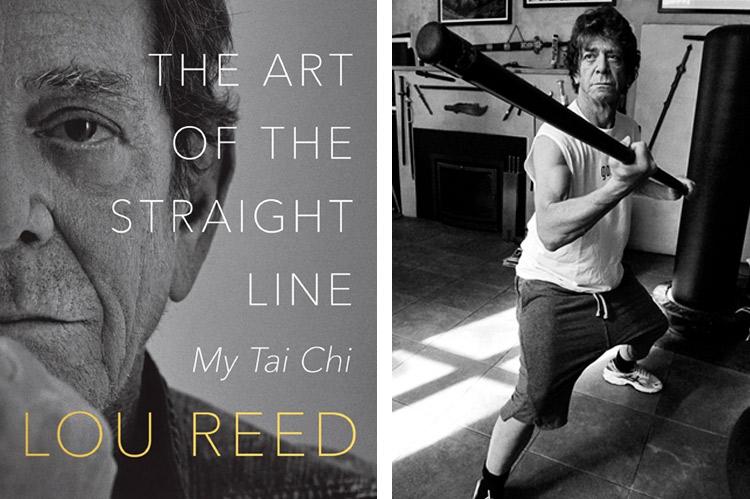

“The Art of the Straight Line”

Lou Reed

HarperOne, $39.99

Learn from a master. Lou Reed, known as a rocker "waiting for the man," with substance issues not to mention hepatitis and diabetes, studied tai chi with masters. Advocating the martial art as practice and health management, much as the film director David Lynch promotes transcendental meditation, Reed's writings, a prime source for his recent book, "The Art of the Straight Line: My Tai Chi," were meant to teach others what he learned in devoted study of teachers before him.

"What is Tai Chi? The Chinese say you meet the hard with the soft, the yin with the yang, the down with the up." Sound woo-woo? Well, no.

Laurie Anderson, the avant-garde composer and musician who married Reed in 2008, assembled his "scattered notes" for the book, which he had planned over years before he died in 2013, determined "to mature like a warrior." Add articles from Kung Fu magazine and other places, facsimile notebook pages, and interviews with friends and creative collaborators.

She writes, "He could be quite humorous and serious at the same time, motivating others, correcting others." A real teacher.

In her foreword, Ms. Anderson calls the title "pure Lou"; if tai chi is all circles, he wanted to "move through circles without losing your sense of direction and your overall goal." The book explains how a practice rescues a life and comes to define that life.

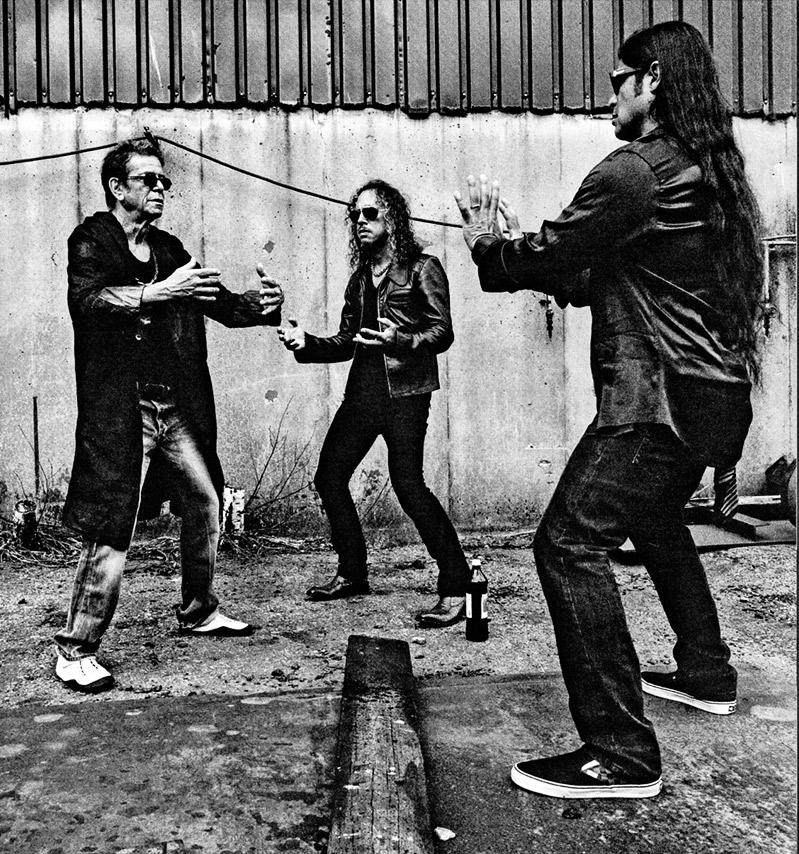

Even if you learn little about tai chi here, you get a rich glimpse of Lou Reed from photos: of Reed practicing at home and with Ren GuangYi, archival shots of Reed at various stages of his music career, Reed with others, exchanging insights from friends in varied disciplines, such as the painter Ramuntcho Matta, the music producer Hal Willner, the poet Anne Waldman. Collaborators in music, theater, and film, among them Robert Wilson and Julian Schnabel, weigh in on Reed's dedication to tai chi as a mindful, physical, spiritual, artistic practice.

Interview segments begin with how they met. Ramuntcho Matta, founder of Lizieres, a cultural center near Paris, son of the surrealist Roberto Matta, and a tai chi practitioner, met him through William Burroughs on Union Square. His watercolor of Reed from 2016 is included among other illustrations. Anecdotes abound, as if each friend is paying a shiva call, recalling their fondest moments with Lou.

Scott Richman recalls dubbing him "the Larry David of rock and roll" after his fussing about food on tour.

Bill Berger, tour manager and lighting designer, remembered that under Clinton, Lou was invited to the White House, a request from the visiting Vaclav Havel, the Czech president at the time. This was two weeks after the Monica Lewinsky story broke, and Berger had to submit a set list. White House personnel worried that Tipper Gore would object to the lyrics to "Dirty Blvd." At the state dinner, though, everything was fine; Tipper was tapping her thighs to the beat, and Henry Kissinger, Mia Farrow, Clinton, and the first lady seemed happy, as Lou sang about "the TV whores . . . calling the cops out for a suck."

Ms. Waldman reminds us that he was a poet, comfortable in downtown poetry circles. (I remember one night at St. Mark's Church, Lou Reed read his poems, opening for Allen Ginsberg, who sang his words accompanied by his harmonium.) Poet to poet, Ms. Waldman wrote one for Lou:

lou lou lou lou,

loosens

his mortal loop,

meets death in love

with softness

tai chi — the

boundless first

part of

survival's trickster

Masquerade.

As metaphor, "The Art of the Straight Line" works as a picture of life's direction. Ms. Anderson describes the Tibetan 49-day rituals associated with the Bardo, practiced after Reed's passing, celebrating his shift in consciousness.

In a time when he's remembered in Todd Haynes's 2021 documentary about the Velvet Underground, and the recent expansive exhibition at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, where his archive is housed, this book presents Lou Reed looking at himself through a specific lens, and apart from any memoir, it offers the man as he moved and breathed.

Regina Weinreich is author of "Kerouac's Spontaneous Poetics," editor of Jack Kerouac's "Book of Haikus," and co-producer/director of "Paul Bowles: The Complete Outsider." She lives in Montauk and Manhattan.

Lou Reed was living in Springs when he died in 2013.