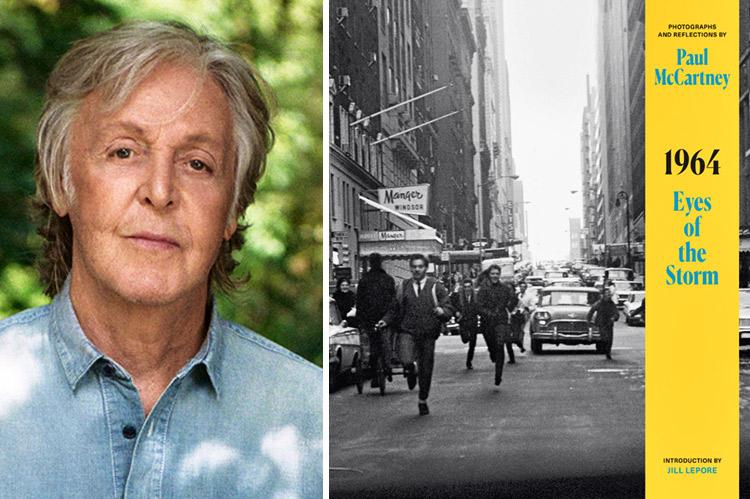

“1964: Eyes of the Storm”

Paul McCartney

Liveright, $75

Surely, the Beatles were the most photographed group of the 1960s, and just as surely Paul McCartney is by far the most prolific of the Fab Four, releasing some 30 albums, under his name or with his 1970s group Wings, since the Beatles' breakup.

Beyond music, Mr. McCartney, who owns a house in Amagansett, has tried his hand at painting and poetry, has acted in several films, and has expressed at least a little apprehension over appearing to present himself as a Renaissance man.

But, at a remarkably youthful 81, he remains engaged with the world and the world remains enthralled by him. The Star reviewed "Paul McCartney: The Life," a biography, in 2016, "The Lyrics," a massive tome of song lyrics and the artist's recollections about them, in 2022, and, earlier this year, "The McCartney Legacy," an exhaustive examination of just four years of his life and the resulting music produced.

Mr. McCartney has most recently added "photographer" to his artistic endeavors with "1964: Eyes of the Storm," a collection of 275 photographs he (mostly) took, with a then newly acquired Pentax camera, late in 1963 and early in 1964. With the coining of "Beatlemania" and the band surging to worldwide acclaim seemingly overnight, Mr. McCartney's recently rediscovered trove documents a unique moment in history.

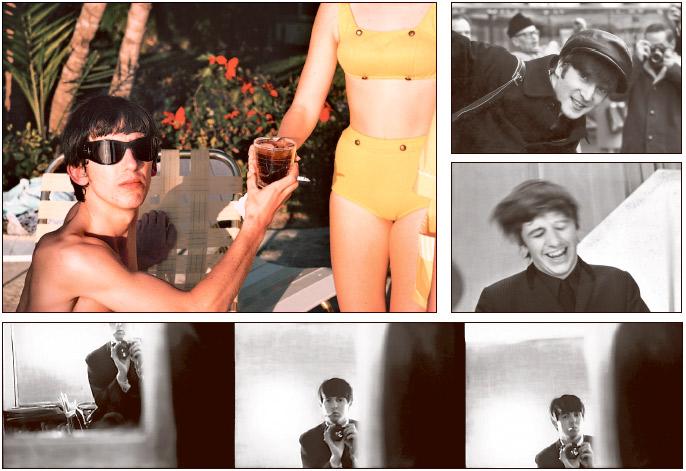

Paul McCartney Photos

"1964" chronicles the band in their native Liverpool, England, in the last moments before "the storm" hits; London, to which they necessarily relocated in 1963; Paris, where they performed for three weeks early in 1964, during which they learned that "I Want to Hold Your Hand" had topped the charts in America; New York, where the storm reached maximum strength with appearances on "The Ed Sullivan Show," seen by scores of millions; Washington D.C., arriving by train and where they played their first American concert, and Miami, where their world exploded into glorious color and they could briefly, finally exhale and enjoy the fruits of their considerable labor.

Mr. McCartney shares recollections of each city and observations of many of the individual photos. Also included are essays by the director and a senior curator of London's National Portrait Gallery, where an exhibition of photos in this collection will conclude on Oct. 1, and "Beatleland: The World in 1964," an outstanding examination of the time by the historian Jill Lepore, also published in June in The New Yorker.

"I have to emphasise that I'm not trying to claim to be a master, only an enthusiastic photographer who happened to be in the right place at the right time," Mr. McCartney writes in the foreword. Yet his photography is quite good, albeit with the advantage of photogenic subjects like John Lennon, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr.

Surrounded by photographers who ceaselessly documented their every move, he writes of absorbing tips from these professionals, but his creativity clearly extends to this visual medium. Subjects are cleverly framed, and Mr. McCartney has a keen eye, or at least uncommonly good timing, for capturing revealing imagery.

"Looking at these photos now, decades after they were taken, I find there's a sort of innocence about them," he writes. "Everything was new to us at this point. But I'd like to think I wouldn't take them any differently today."

His photos capture the Beatles' elation in the first flush of superstardom, as well as that of their manager, Brian Epstein, their producer, George Martin, and others in their circle. Trapped in hotels, dressing rooms, cars, and airplanes, his bandmates are unguarded, sometimes clowning, sometimes exhausted, other times introspective. In particular, some photos of Lennon, all of 23 years old but carrying a lifetime's worth of anguish, document him at once euphoric and forlorn, brash and vulnerable.

Along with the people of 1963 and '64, the places depicted are striking in how much has changed, and how much has not. One photo depicts Columbus Circle in Manhattan, "a very mid-century New York scene," according to its caption. From the train bound for Washington, "I enjoyed the American landscape we saw en route and the workers we passed," Mr. McCartney writes. Billboards, road and rail infrastructure, and nameless, ordinary people, like rail workers holding snow shovels, depict fleeting moments now six decades gone.

At $75, "1964" is a big-ticket book, but given the offerings inside, it is well worth the investment. Ms. Lepore's essay is first-rate. On the news of President Kennedy's assassination, on Nov. 22, 1963, she writes, "You could tell, even in that minute, that the world was turning. It was as if you could feel it, rotating, and moving through its orbit. It was something, maybe, that you could try to catch on film."

By 1964, she writes, "The Beatles became the first truly global mass culture phenomenon: They'd been shaped by a wide, wide world, and their music reached that world, bounced by satellite and flown by air freight and shipped by container ship. . . . By the time Beatlemania broke out, the sun had set on the British Empire. But the age of globalisation had begun. And something more, too, was just catching fire: an unsettling, an upheaval, revolutionary. Time magazine, writing about The Beatles, called it 'The New Madness.' "

Especially poignant, with the luxury — or the burden — of hindsight, is a photograph depicting, up close, a Miami police officer's revolver and bullets, snug in a holster, "the first time I had ever seen something like that," Mr. McCartney's caption reads. "His gun was framed perfectly through the window, and I managed to focus on his gun and ammunition," he writes in the foreword. "It was still slightly shocking for us to see a gun in real life, as we didn't have armed police officers back home. I don't like guns. The violence they're responsible for is the antithesis of everything The Beatles stood for."

But the Beatles looked so innocent in 1964. In a conversation with Conan O'Brien in Manhattan in June, the podcast host observed, "We know how the story turns out" in 2023. "We all know what happens. But especially in these early photos, you guys don't know yet what's going to happen. It's a mystery to you in these moments. . . ."