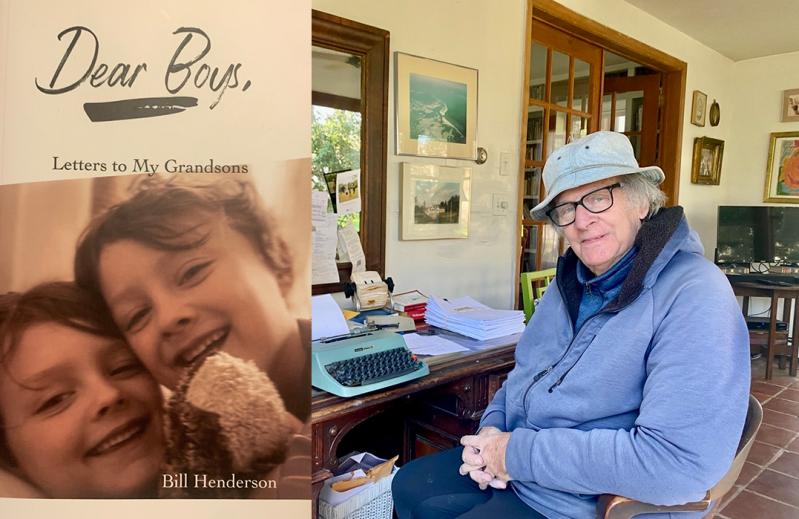

“Dear Boys”

Bill Henderson

Pushcart Press, $20

The letters in Bill Henderson's "Dear Boys" are addressed to twin grandsons in anticipation of their future adolescence — for they are only 5 years old as of the writing. The writer is an octogenarian. The themes, advice on how to live a good life, are embedded in autobiographical tales, some weighty and some light, following the chronology of the author's own experience. In other words, this is a memoir with a target audience, or so Mr. Henderson hopes.

To this sympathetic reader, Mr. Henderson is a nonconformist who has wrestled with the enigmas of existence all his life. "You guys or your children may never know a childhood like my own, infused with God, as an unspeakably horrifying World War raged." Maybe. For Mr. Henderson, the struggle with belief and skepticism has been ongoing, and it is not really clear where he stands at any given stage, but he probes the questions deeply throughout.

He is also pessimistic about the state of the world his grandsons are inheriting. "So much will confront you in the years ahead. We have left you a morbidly ill planet, ruined by greed, power grabs and shopping madness. . . . Even worse is the rising tyranny of technology."

He continues: "As I do, you guys probably still live in that fear of total extinction. . . . Our mad inventors continue to take us near oblivion, through bombs and robots or whatever has been concocted in your day. They invent stuff just because they can but they are often leading us into disaster. Resist the amoral wizzbangs."

Reading these parts of the book put me in mind of Anthony Newley's 1960s musical "Stop the World, I Want to Get Off."

We hear of his early loss of innocence about the goodness of the world when his kindergarten teacher, Mrs. Hotchkiss, "tortured us. But she was the teacher, the supposed good person."

Then there is the episode in which Billy Graham, at a tent revival in Ocean City, N.J., tells a parable about a lapsed man and his Jaguar sports car, who, given three chances by God, begged him for another chance "but God had had it," and how "the man parked his Jaguar on the Ben Franklin Bridge and jumped off." So much for the dark.

On the light side, there are very amusing tales about sex in adolescence. "Pop and the preachers were silent about sex," so he learned by trial and error. We hear about a teacher, Mr. Fritz, whose class on mating habits included observing a praying mantis "servicing" his mate and getting his head bitten off by her in reply, and of rumors about "doing it" and taking off your clothes "to do it." So then, "I resolved never to take off my clothes with a girl. Ever."

"Dear Boys, nothing in my 80-plus years has been harder than surviving puberty." Don't we all remember the rage we ourselves felt when some well-meaning adult would say at one of our teenage birthday parties, "Enjoy! These are the best years of your life!"

Mr. Henderson is touching about body changes in adolescence. He says, "I couldn't ask the other boys what was happening to me." The more he learns about the mysteries of sex, the more he fears it is a sin — shadows cast by memories of his religious upbringing and devout father.

His advice to his grandsons? Forget all that. "I do know one bit — sex in thought, deed and self-identity will be a huge chunk of your post-puberty life. From others you will receive a torrent of advice. . . . Ignore all that. Stick to what you know, in your heart and mind. And above all be kind to your dates. . . ."

There are some longish memory sections about his grandmother, his mother's death, meeting his wife, Genie, the arrival of his daughter, Lily (the boys' mother), in his life, and the building of his tower in Maine.

There is a through-narrative about various dogs that were his soul mates, essential partners. They are — for Mr. Henderson and for many of us — the antidote to all that is wrong with the world: "Slow down. Make room for love and wonder. Despair is not an option. Here is another reason to own a dog."

The bottom line of his message to the boys — and to us — is summed up in this dialogue with a college friend: "I announced that I was leaving school. . . . Mark Marshall came to my room."

"Don't go. I'll miss you," he said. "Shave away the nonessentials and you'll find the real."

Somebody then asked, "Do you think war is always wrong?" The answer came, "That depends if you think life is sacred or not."

"Life indeed is sacred," Mr. Henderson writes, and, dear boys, that is "probably all we will ever need to know about anything."

Ana Daniel, a regular book reviewer for The Star, lives in Bridgehampton.

Bill Henderson is publisher of the Pushcart Press. He lives in Springs.