“Lost Long Island”

Richard Panchyk

History Press, $24.99

Richard Panchyk makes a devastating if overlooked point in opening his latest history survey: Long Island's been weathering losses since 1898, when New York City subsumed Brooklyn and Queens, effectively decapitating the 118-mile fish-shaped pile of glacial leavings. Because no one is referring to anything west of the Nassau County line when they say "Long Island," geography be damned.

His book, out last week, is "Lost Long Island," each of its 21 chapters exploring a different disappearance, plenty of them eye-opening. "Lost Quaker Abolitionists," for one, looks at populations of the faithful concentrated around Jericho and Westbury "who went from being persecuted to helping stop the persecution of others," and ahead of the game at that, registering manumission papers roughly 90 years before the Emancipation Proclamation.

Curiouser, "Lost Tree Moving" doubles up, incorporating a lost business and a lost customer base — the Gold Coast in its heyday. Starting in the 1890s, it turns out, Isaac Hicks and his son Edward "would offer these new property owners," the newly rich, "nearly full-grown trees of all types that would save up to twenty-five years of time." Using patented equipment, they would "transport huge mature trees up to fifty feet tall and plant them successfully on properties all across the north shore of Long Island."

Or consider the ultimate form of recycling, in "Lost House Moving." The author points out that "from the mid-1600s through the end of the nineteenth century, home building technology did not advance that greatly." Saving "sturdy and well made" old houses "made sense and saved money."

This involved "the use of horses or oxen to pull a building along a system of wooden rollers." Later, "movers used screw jacks to push a house along greased steel beams that served as a track."

Maybe the oldest example on the Island is on the North Fork in Cutchogue, the Horton-Wickham-Landon House. "Built in 1649 in Southold, it was disassembled board by board and moved several miles west to Cutchogue in 1661."

In contrast, though Panchyk tends to keep his focus west of here, on the South Fork the sad tally of lost historical houses has not let up — an example not in the book is the 2022 destruction of the mid-1700s Capt. John Sanford House on the corner of Ocean Road and Paul's Lane in Bridgehampton.

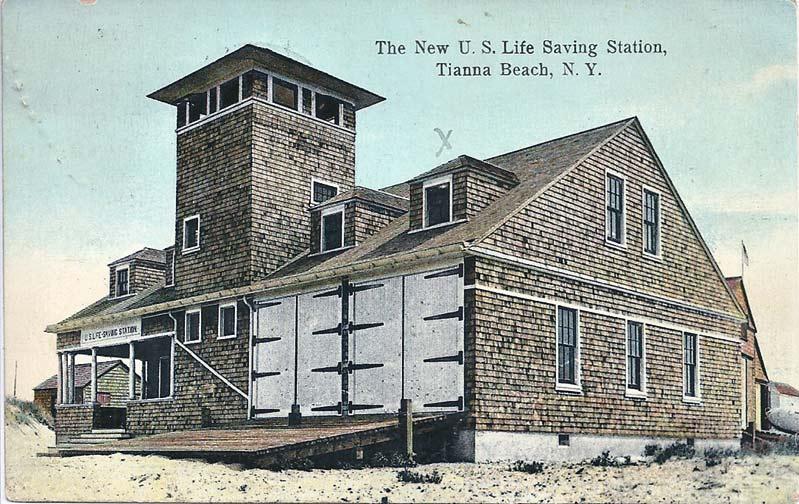

Quogue Historical Society

Better preservation has followed the coastal lifesaving stations. Wrecks like that of "the British sloop-of-war Sylph, which got lost in the fog and wrecked off Southampton in 1815," leaving only six of the crew of 133 alive, later led to a congressional mandate for lifesaving stations across the South Shore, from Fire Island to Quogue to Amagansett, the latter a remarkable restoration. A station at Tiana Beach in Hampton Bays is another, while several others exist as private residences.

"As of 1901, there were thirty-three lifesaving stations on the coast of Long Island." And the action they saw? "Between 1894 and 1903, 200 vessels were stranded on the Atlantic Ocean coast of Long Island, 114 vessels stranded on the Long Island Sound coast, and 6 more in Gardiner's Bay."

In all, nationwide, the service "saved an incredible 186,000 lives due to the efforts of its capable and dedicated crews." It merged with the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service in 1915 to form the Coast Guard, through which "its spirit lives on."

In an often lamentable cataloging of a vanished world, this is one positive progression it's hard to take issue with.