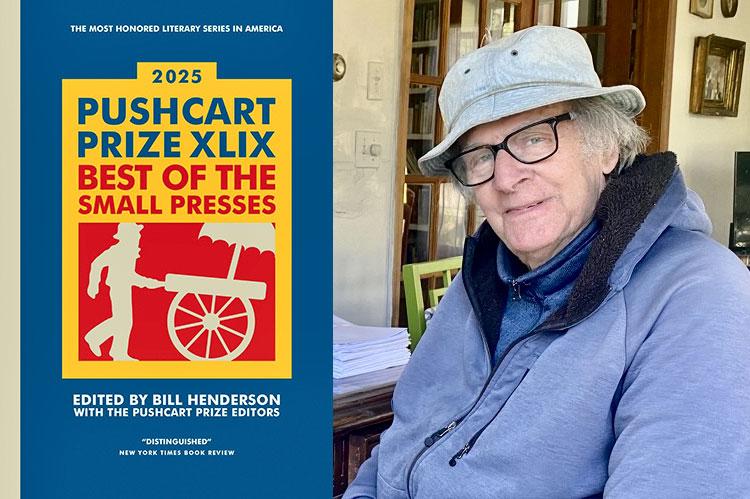

“Pushcart Prize XLIX”

Bill Henderson, Editor

Pushcart Press, $19.95

The annual Pushcart Prize anthology of fiction, poetry, and essays is a barometer of our culture, the canary in the coal mine — or the crow. There are a lot of crows in this year’s edition, which makes sense. They’re the cleanup crew.

Two years ago, when many of the pieces had been written during the height of Covid, the collection’s guiding metaphor was Pompeii: People caught unaware by sudden devastation, their interrupted lives preserved in the lava of sentences.

The word that echoes in the 2025 anthology is aftermath. Now, we are picking through the ruins, excavating new meaning, adapting to permacrisis — like the clever crows of Karachi who have learned to build nests out of plastic garbage. I heard about them in Rafia Zakaria’s essay “The Crows of Karachi,” in which she mentions the few still-existing Zoroastrian ossuaries where the dead are placed so carrion birds can dispose of their flesh, “performing the task of transformation from the darkness of death into the continued vitality of life.”

The Pushcart table of contents reflects our collective aftershock, with titles like “Afterlives,” “What Is Left,” “Why Write Love Poetry in a Burning World.” There is something determined about the lack of question marks in those last two titles. The writers are no longer surprised; instead, they’re taking stock.

This being the subversive Pushcart anthology, the actual canary in the coal mine has quietly quit. In Sophie Hoss’s story “Good Medicine,” the defective bird is given to the family of the coal miner who died because of its failure to register toxic fumes by dying itself. Instead of snapping its neck — the first thought that comes to the widow — they adopt it.

This year’s Pushcart Home for Adopted Canaries comprises 71 pieces from small presses and literary magazines, culled from some 10,000 submissions by Bill Henderson and his band of editors. All of this bursts out from a backyard shack in Springs belonging to Mr. Henderson, who founded the prize 48 years ago.

It includes fresh writing by established practitioners like Andre Dubus III, Joyce Carol Oates, Mary Gordon. But for me, the excitement is discovering emerging writers and independent publications — Deep Wild, Hedgehog Review, Flyway, Baffler, to name a few — not bound by the self-censorship of commercial considerations or the actual censorship of the Floridian variety.

New Take on Old Testament

Not surprisingly from an iconoclastic publication in a year of upheaval, there is a lot of questioning of the truisms of the past. Some of the best work recasts religious myths, such as Danielle Coffyn’s feminist take on Original Sin, a poem in which the title leads directly into the verse, as if there’s no time to waste:

“If Adam Picked the Apple”

There would be a parade,

a celebration,

a holiday to commemorate

the day he sought enlightenment.

Or the myths are applied to our lives today and found to be ill-fitting. Can we still live by the values handed down to us over millennia? You’ll find some unsettling answers here.

Austin Smith’s story “The Nineteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time” asks the question: What if Christ came back to life, in a church in small-town Illinois? His suffering — redolently depicted by Mr. Smith, down to “the bones in his palms . . . shattered and splayed out through the bloody skin like strands of fiberglass” — is too real for the congregation to bear. They debate what to do with him.

“Medevac him to Monroe? Trying to lighten up what had become a very intense situation, someone asked what would happen if he didn’t have health insurance.”

When the solution comes to them, it involves a thirty-aught-six that one congregant happened to have in his truck.

One of the thrills of reading the Pushcart is seeing the same theme refracted through different genres. Mr. Smith’s story of the tragic re-resurrection could be read in conjunction with two unstinting looks at what guns can do to the human body: “Ballistics,” an essay about killers and their weaponry, written in an exploded, staccato form by Leslie Jill Patterson, who works on death-row cases with public defense attorneys, and Abby E. Murray’s poem “Self-Portrait as a Coriander Seed,” about what an assault rifle’s round can do to a child’s body, and about what the threat of this violence does to the human soul: “we just keep getting smaller, more hardened.”

It’s not all 24/7 apocalypse, though. In Adia Muhammad’s romp of a poem, “The Virgin Mary on MTV’s Teen Mom: Nazareth,” Mary lashes back at her fellow pregnant moms who are asking, “Who’s the daddy?”:

I hear y’all talking smack

bout my baby bump.

. . .

You messin with the vessel. God-chosen. Savored

like a low-key wine. Even my cramps holy. See me

ridin side saddle to PTA meetings. You havin

a doctor? Lawyer? That’s cute. Savior.

And he gone have his mama’s eyes.

Similarly, Lily Greenberg imagines from the perspective of God’s wife (why do we never hear about Her?) a much more visceral creation story than the original Old Testament:

“The Beginning According to Mrs. God”

was a mess

of drool and semen and teeth.

. . .

You who want the beginning to be clean as a word —

but this was before words.

A different sort of reinvention of faith is chronicled in the essay “Growing Up Godless” by Robert Isaacs, a professional church chorister from a family of atheists who goes through the motions every Sunday for years:

“It seemed so repetitive — all the same words in the same order week after week, all those elderly ladies slowly shuffling forward for communion (an act which struck me, the teenage Indiana Jones peering over the pew, as ritual cannibalism).”

And then slowly he comes to feel the presence of a god in beauty — a chorus of bees on a summer afternoon in Maine, the digits of pi, J.S. Bach, although he allows that “Constructing a god from scratch, drawing on neither church nor bible, is a challenge.”

From the Headlines

The Pushcart anthology is one of the few places that gathers fiction and poetry “ripped from the headlines.” In the story “Winners,” Merritt Tierce traces the intimate effects of today’s anti-abortion laws on a woman potentially dying from a miscarriage. A Texas doctor afraid to perform an abortion-like procedure to save her explains the lethal absurdity codified by the law.

He has to discharge her first, “to send me away to almost die before he could make any attempt to save me and/or some of my reproductive organs. The thing about almost dying is, you can’t really know where the line is until you actually die. Then you know where the almost-dead line was, but you’re dead, so it doesn’t matter.”

And in “Gary’s Way,” Andre Dubus III makes personal a different kind of aftermath in a suspenseful story narrated by a woman trying to leave her husband of 17 years after she learns he’s been involved in a violent incident during the Jan. 6 Capitol riot.

The difficulty of getting our bearings in this new normal is conveyed by Jessica Greenbaum’s lyrical poem about the rituals of our era, “Each Other Moment”:

We turned location back on.

We were resetting our passwords.

. . .

We were making suggested

go bags and stay bins for the likely

floods and fires. We were

wondering why men only

gave us one star. We looked to

the sky for how to help any

anything at all. We hit retweet

on the full moon . . .

. . . We turned location

back off. We were innocent but

each other moment we were lost.

Come to think of it, you might want to locate yourself before you start your journey into the Pushcart Prize collection with the essayist Brenda Miller’s “Care Warning,” a beautiful meditation on grief couched in a wry, extended trigger warning. I have noticed in the last few years the undergraduates in my creative writing workshops kindly warn their classmates of potentially triggering elements when they share their stories. I want to say to them: You’re writing short fiction! If it’s any good, it will be disturbing.

But perhaps this trigger warning itself is integral to the story, a way to recognize that stories are not read in a vacuum. Here’s how Ms. Miller begins her caution:

Before I get going, I just want to give you a heads-up that this essay references childhood (and adult) trauma, so take care of yourself. There are some dubious clothing choices and bad-hair days, and there’s that time when I thought a guy wanted to kiss me, but it was only because my brother and his friends dared him. . . .

And just a note: the global pandemic hovers around the edges here, because it still hovers over everything we do. . . . So if you’d prefer to put the pandemic firmly in the past, you might want to sit this one out.

She ends by embracing the reader with her words: “Listen: we’ve got each other now, you and I, and, in the space between these lines, a whisper that says, Take care, take care.”

We’re in this together. After all, to reassure Lily Greenberg’s Mrs. God, we do now have words — ways to process, to mourn, to write new liturgies.

As I read this collection, I kept coming back to the poet Katie Farris’s question, which could be the refrain of this year’s irrepressible anthology:

Why write love poetry in a burning world?

To train myself in the midst of a burning world

to offer poems of love to a burning world.

Alexandra Shelley, who lives part time in Sag Harbor, is an independent book editor and professor of fiction writing at The New School.