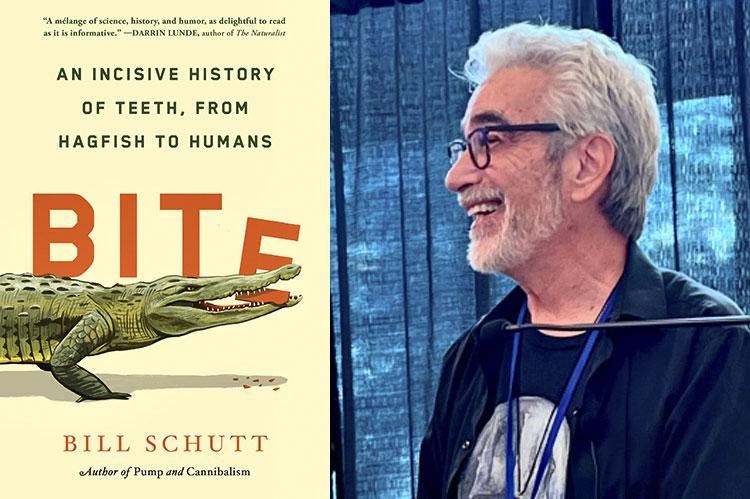

“Bite”

Bill Schutt

Algonquin Books, $31

Bill Schutt’s “Bite” is informative, at times amusing, and exhaustive, offering everything you ever hoped to know about teeth, and then some. But you can skip around and dip in where your curiosity takes you — bats, horses, alligators, snakes, everything that bites, including us.

Start with bats (the writer’s specialty). Mr. Schutt focuses on vampire bats, which live on blood alone. “With their diet supplying little to no fat or carbohydrates, an inability to store energy is a serious disadvantage for vampire bats. As a result, they can starve to death if they don’t get a blood meal within forty-eight hours.” But there is good news for us locals. “There are no wild vampire bats in the United States, Asia, or Europe.” What a relief!

Regarding snakes, we learn that “according to the World Health Organization, over one hundred thousand people die each year from snake bites,” and we have plenty of poisonous snakes in the United States. So beware!

There is happier news when it comes to whales, of which there are two kinds: toothed, like orcas and dolphins, and baleen, like blue whales. The sad part here is that we are their enemies.

Baleens, the biggest, eat very small things and work as a team when bubble-netting. This is a wondrous spectacle that I myself have witnessed in Alaska. A number of these huge mammals form a circle in the deep and, after emitting a signal, blow bubbles into the center that paralyzes a school of small fish passing by, which the whales swallow as they rise. Once at the surface, they fluke together (tails in the air) and swim on to another catch. Worth the trip to Alaska.

But baleens don’t bite, they are toothless. Instead they gulp, filter, and swallow. So, if you were to be swallowed by a baleen whale you would go down whole — like Jonah — and perhaps be regurgitated to live another day. Just kidding.

Back on land, “Horses and their relatives belong to the order Perissodactyla, which contains three extant families: Equidae (horses, asses, and zebras),” rhinos, and tapirs. Incidentally, someone told me the other day that zebras are black animals with white stripes and not the other way around. Perissodactyla are animals with hooves, “which are, in fact, modified toenails.”

This zoological order “comes with a rare, well-preserved sequence of transitional fossils from different geological periods . . . together, this evidence not only provides a fairly complete picture of horse origins but also the successes and failures that took place over the fifty-million-plus-year journey of this surprisingly diverse group.”

Because horses’ incisors grow during adulthood (in contrast to our own receding gums), “tooth length can serve as an indicator of equine age.” Ergo, St. Jerome’s commentary on Paul’s letter to the Ephesians: Noli equi dentes inspicere donati. You may suspect the gift horse is too old to work, but it would be rude and thankless to check out its age.

The study of evolution through the examination of fossil and extant teeth might suggest that necessity is the mother of invention, but as Mr. Schutt reminds us, “Adaptations . . . can’t be ordered up just because creatures happen to need them. Mutations might simply not occur, and furthermore, not all mutations are beneficial — in fact, most are either detrimental or have no significant effect. In other words, mutation is not assured, and when mutations occur, they do not ensure adaptation.”

It is all a roll of the dice. Could nature have produced unicorns? Maybe. It has produced narwhals, a whale species, which sport unicorn-like single tusks that evolved from their canine teeth — function uncertain.

And here is a surprise: “In 2021, Princeton University professor of ecology and evolutionary biology Shane Campbell-Staton and his colleagues published a paper in Science [demonstrating] that during the Mozambique Civil War (1977-1992), the African elephant population . . . experienced precipitous decline . . . as elephants were slaughtered by poachers. . . . As a result, a strong human-driven selection for tusklessness arose” and “the percentage of tuskless females in those areas increased from 10.5 percent to 38.2 percent” over 20 years. (The complex reasons why this did not apply to males are provided in the text.)

And so, on to our American teeth. We learn a lot about poor George Washington’s false teeth. Apparently, there are four surviving sets of them, herein described and illustrated in detail. They sound horrible. His dentist was one John Greenwood, who “sought to remedy Washington’s considerable dental woes . . . and pulled Washington’s last remaining tooth in 1796, preserving this treasure in a tiny glass case that he hung from his [Greenwood’s] watch chain.”

As a culture, Americans can be said to be obsessed with teeth, the whiter, the better — as white as bathroom fixtures if possible. Apparently this preoccupation goes back to our founding fathers: “The reason Washington wore dentures that were uncomfortable and useless for eating had everything to do with his distinguished place in the newly minted American experiment with democracy. His ability to speak well and present a strong, attractive physical appearance were direct reflections of the nation’s character — this, at a time when the new country could not afford to present itself as anything less than morally upstanding, smart-looking, and powerful.”

Two-hundred and forty-eight years later, this necessity seems to be operative still.

Finally, to “an issue of related and great importance: namely, the tooth fairy. . . . According to Garrett Williams, self-described ‘lawn-game enthusiast’ and distinguished tooth fairy expert, press coverage of the tooth fairy’s exploits began on September 27, 1908, in a short piece by newspaper reader Lillian Brown, published in the Chicago Daily Tribune” recommending an incentive for children to allow a loose tooth to be removed.

Our narrator adds that these days, “loose-toothed tots may want to keep an eye on the stock market, since the average haul from the tooth fairy typically tracks the ups and downs of the S&P 500.”

Mr. Schutt concludes, “Toothless creatures notwithstanding, the importance of teeth in the natural world and in the lives of humans, past and present, cannot be overemphasized.”

Read on and learn why.

Bill Schutt’s previous books include “Cannibalism: A Perfectly Natural History.” He is a professor emeritus of biology at Long Island University’s C.W. Post campus.

Ana Daniel, a former academic and Wall Street consultant, regularly reviews books for The Star. She lives in Bridgehampton.