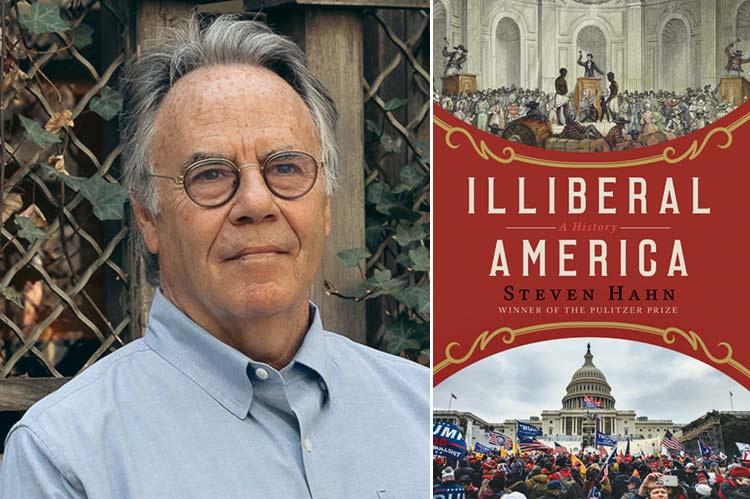

“Illiberal America”

Steven Hahn

W.W. Norton, $35

We hear, we read that the American Republic, as we (think) we have known it, is in danger, and the main message of "Illiberal America" is that many of the threats to our liberal republic we see today have been present in our culture from the start. This book is a densely detailed history perhaps not for the casual reader, but because it is most timely and relevant, I will try to offer here a synopsis of its principal arguments rather than a critical analysis.

To start with, what does Steven Hahn, a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian, mean by the term "liberalism"?

Hahn answers: "In its most robust portrayals, liberalism imagines a political order based on rights-bearing individuals, wide-ranging civic inclusiveness, highly representative institutions of governance, the rule of law and equal standing before it, the use of democratic (mainly electoral) methods of representation, and the mediation of power by an assortment of civil and political devices (courts, regulations, organizations, and associations)."

"Illiberal America" traces limitations and compromises to this notion of liberalism from the start of British colonialism in America, pointing out that during the first two centuries of settlement 75 percent of the 800,000 who came were coerced laborers: indentured workers or slaves. The book reports that during the constitutional period anti-Federalists in rural and village areas feared "the consolidation of power the Constitution brought about at the expense of states."

"Anti-Federalism therefore had special appeal to those who . . . saw themselves as members of communities bounded by ethnicity, culture, faith" and "were wary of outsiders and distant legal and political institutions."

As is now well known to most, many of our Founding Fathers were slave owners and willing to compromise the ideal that all men are created equal. They meant only white men, not white women or anybody else. They were willing to agree that each slave could count as three-fifths of a person in the population base of states for the purposes of assigning seats in the House of Representatives to the benefit of Southern states.

This text often reminds the reader that "some traditions that appear to have deep history are often more recent creations, constructions, or inventions." Abolitionism is a case in point: During the pre-Civil War 1830s, leadership of anti-abolitionism counterintuitively "came chiefly from the ranks" of those "considered to be the old elite, the aristocracy of the North." Even after emancipation, the personal autonomy signified by the term "free labor" "fell under the rules and understandings of master-servant jurisprudence" for both Blacks and poor whites.

By the time of the massive immigrations to the United States during the 19th century, national and religious identity (Irish, Italian, Jewish, Mexican, Chinese, Catholic) joined race as a magnet for prejudice. "The alarms were sounded most loudly by Protestant elites who fretted about a political world they had lost and a worrisome new one they seemed to be inheriting, one in which tens of thousands of restless workmen, foreigners for the most part, were overrunning the country."

Both Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson were concerned about racial corruption of the American body politic — a concern that resonates today.

During the first half of the 20th century, "the marriage of science and eugenics suggested to . . . political leaders that civilization could be advanced domestically in the face of crime, unrest, and cultural frictions . . . Americanizing those who could assimilate, excluding those who could not, and surveilling social reproduction."

Further, organizations like the Ku Klux Klan, which may have numbered as many as five million in the mid-1920s, "clearly resembled the fascist movements of Europe, especially at the grassroots." In turn, "far more than Benito Mussolini, it was Adolf Hitler and the Nazis who looked to the United States and its history as possible models," giving special attention to "American racial policies . . . for denying citizenship to Jews and criminalizing intermarriage."

In a shocking paragraph, Hahn tells us, "German and American eugenicists were in touch from early in the 20th century, and new American philanthropies . . . hoping to 'save' German science after World War I, offered ample aid during the 1920s and 1930s to German institutions engaged in eugenics research. One of the beneficiaries of Rockefeller funding was Josef Mengele."

These philanthropies were not operating in a social vacuum. "The German American Bund was established in 1933 as a pro-Nazi paramilitary organization which would claim thousands of members." (See the PBS "American Experience" documentary "Nazi Town, USA.")

While "the early 1960s are widely viewed as the salad days of modern liberalism, the radically charged urban explosions of the mid-to-late-1960s, together with the disastrous defeat in Vietnam, many believe, marked the beginnings of the country's turn to the right."

"It is commonplace to regard the movements against the E.R.A. and abortion rights" in response to "the liberalism and new rights demands of the 1960s as backlashes. . . . Yet such a perspective ignores how the 1950s and 1960s saw the growth of illiberal and radical right-wing ideas and activism in a variety of forms that fed much of what was to follow. Here, deeply rooted threads of anti-communism, anti-statism, vigilantist localism, and racism were strengthened by newly politicized Protestantism . . . especially in the newly emerging Sunbelt."

This brings us closer to the present. We all remember George Wallace, Alabama's favorite son, four times elected governor thereof, who ran twice in the Democratic primaries for president (1964 and 1972) and in 1968, as in independent candidate, packed Madison Square Garden, about which a journalist wrote at the time that Wallace was "the ablest demagogue of our time, with a bugle voice of venom and gut knowledge of the prejudices" of his supporters.

With the Reagan administration came the era of neoliberalism, unleashing market-principled individualism and suspicion of the federal state. Supporters were not libertarians or laissez-faire advocates. They supported administrations that would protect property and cut income and capital gains taxes and welfare services. "Nowhere in the United States were neoliberal ends yoked to illiberal means or efforts to take over the Republican Party more directly than in the developing movement of the Christian right, or even more accurately, Christian nationalism."

All of this culminated "when Donald Trump . . . questioned Barack Obama's legitimacy to be president, called on his supporters to 'make America great again,' warned of an 'invasion' of 'illegal aliens' from the south, expressed sympathy for torch-bearing neo-Nazis who vilified Jews, told the white supremacist Proud Boys to 'stand back and stand by,' and eventually insisted that his presidency was stolen by electoral corruption in America's multi-racial cities," thus validating "fears of a race war being waged from the deepest recesses of the state."

Hahn does not take comfort in the idea of cyclicality in history, with right and left replacing each other from time to time in pendulum style. Rather, he sees liberalism and illiberalism as powerful currents running in parallel, with white supremacy as an abiding theme, now strengthened by changing demographics and threatening us with authoritarianism. This may be good news to some, bad news to others.

Ana Daniel taught modern European history at Southampton College. She lives in Bridgehampton.

Steven Hahn is a professor of history at New York University. He lives part time in Southold. "Illiberal America" comes out on March 19.