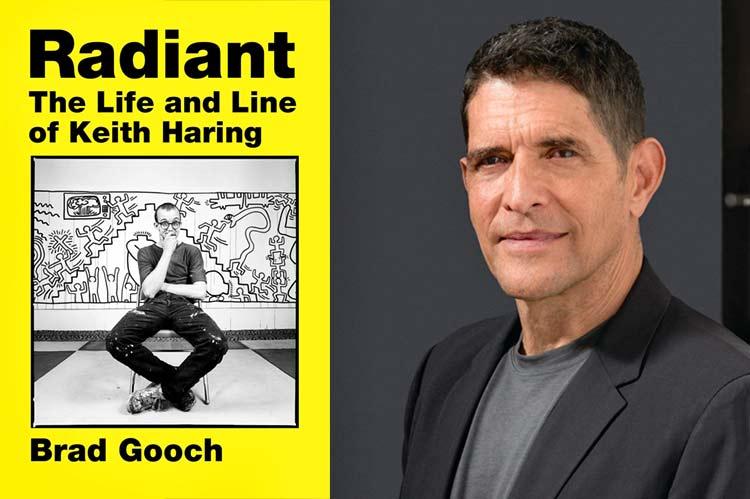

“Radiant”

Brad Gooch

Harper, $40

Recounting the perilous time of AIDS in his memoir, “Smash Cut,” the biographer Brad Gooch tells of Keith Haring sending a signature happy-dance drawing, a bittersweet gesture, to a sick friend, the filmmaker Howard Brookner. This was a short time before he, too, succumbed to the virus, at 31. AIDS did not kill everyone in New York's gay community, but Mr. Gooch, a witness, writes sensitively and unsentimentally about these key arts figures, ensuring a legacy and offering keenly observed details about a life he also lived coming of age as a writer and fashion model.

In so doing, he may be governed by words from Haring’s journal: “I’m not really scared of AIDS. Not for myself. I’m scared of having to watch more people die in front of me.”

In “Radiant,” his turn to Haring as a subject is a no-brainer, an opportunity to continue his assiduous study of 1980s culture.

From hundreds of interviews and Haring’s journals, Mr. Gooch limns the artist’s childhood and development of his distinct line. Early on, in Kutztown, Pa., his father, Allen, an electronics technician, former Marine, and amateur cartoonist, was an influence, giving his son his first crayons. He went from playful kid to true believer, putting up posters as a committed Jesus freak inspired by Billy Graham. Then he turned hippie. Haring bonded with one girlfriend over Alfred Jarry’s “Ubu Roi” and Kurt Vonnegut. He went cross-country with another girlfriend; his sexual preferences changed.

By the late 1970s he arrived in New York City to study at the School of Visual Arts, where, according to the author, he soaked up semiotics, as much a tool as William Burroughs’s cut-up technique. He met Jean-Michel Basquiat, Kenny Scharf, Andy Warhol, and John Giorno.

Unlike Giorno’s memoir, where he writes of Haring as a sweet lover, Mr. Gooch’s biography dwells on neither salacious details nor partners, but his account of the artist’s voracious appetite for nightlife at the baths and bars underscores Haring’s adventurous too-young-to-die spirit. An East Village basement dubbed Club 57 was a formative hangout.

Pulsing penises became as much part of his iconography as radiant babies and dogs; they represented his anti-Reagan political stance as did the slogan Ignorance = Fear / Silence = Death. Variations of Haring’s ACT UP posters are among the fine illustrations in this book, bringing his AIDS activism into focus.

As has often been noted, Haring’s energetic line is so distinct, so popular, so recognizable that his art has been absorbed into the visual vocabulary of our time. Not to hold it against him: There’s the art, and then there’s the licensing. Approaching death accelerated his manic work ethic, and his estate continues this enterprise. A collaboration with Uniqlo resulted in adorable if ubiquitous tees and jeans for kids. Yogurt sold in terra-cotta cups etched with his dancing figures — in the weird flavor “rose” — was a recent whimsical Valentine’s Day sales ploy. Coming soon: The French designer Jean-Paul Gaultier has collaborated with the Haring estate on a fragrance.

Behind it all, there’s real art. Mr. Gooch’s book suggests we look closely at the art as canonical, a recognition obscured by the sheer commerce. An international star by the time of his death, Haring produced as much as if he had lived till 90. Still, as an artist, Haring was a populist, against the prevailing elitist attitudes of the 1980s gallery system, which emphasized keeping things rare, commanding outrageous sums.

Not that Haring didn’t mix in that milieu: He worked for Tony Shafrazi when the gallerist was starting out in New York. “Dressed in a fine suit, with a warmly charged manner and cosmopolitan accent, Shafrazi projected an attitude somewhere between uptown and down, money and art. . . . The dealer Mary Boone was a regular at the openings, as was her artist Julian Schnabel, whose broken-plate paintings . . . were celebrated in the Village Voice as a ‘tantrum in painting’ and a break from austere minimalism and helped prime the aesthetic for artists such as Haring.”

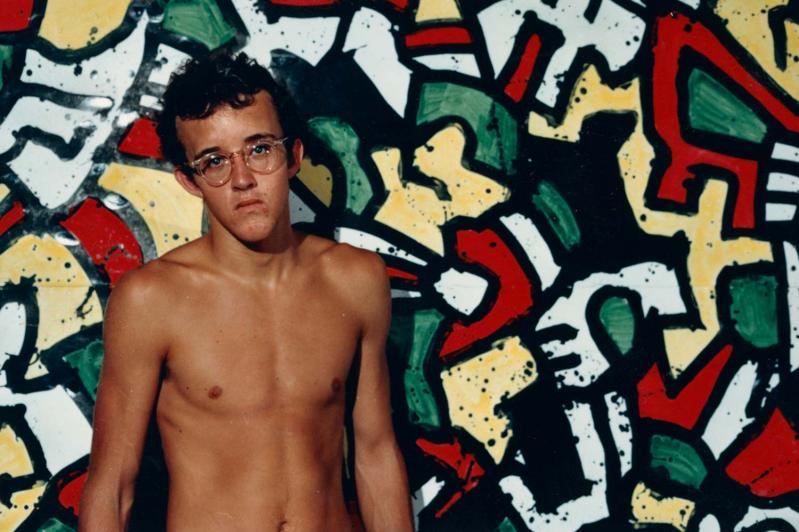

Quoting the curator and dealer Jeffrey Deitch on the social aspects of the job, “Keith was working the bar. He was at the prime of his unique look with very close-cropped hair, and really thin wiry, and these big thick glasses. He looked like no one else on earth. You knew just by looking at him that this guy had something.”

Mr. Shafrazi was impressed with the infectious social energy of the friends Haring brought into the gallery, among them Basquiat and Mr. Scharf. His skill as a scene-maker must have been a big boost. Yet, the author observes, “Keith felt himself to be very much an observer at these openings.”

By contrast, Haring made art on subways, in the street, hoping to garner praise from graffiti masters. He did make his mark in that underground world, while his populist intentions meshed with his celebrity nightlife, including going out to clubs with Andy Warhol. A deep friendship developed. They talked on the phone every day. Kermit Oswald, an artist and Haring’s childhood friend, is quoted as saying they were “like two old ladies,” sharing bits of gossip.

As Mr. Gooch tells it, Haring had been away visiting Kenny and Tereza Scharf in Brazil, out of touch, as they had no telephone or electricity, when he made a road trip to Ilheus to phone his gallery. He stopped by Tereza’s parents’ house in town, and was browsing Warhol’s book “America,” seeing photos of himself skinny-dipping at Andy’s house in Montauk, when he learned of the artist’s death of complications following a routine gallbladder operation in New York Hospital.

The memorial service at St. Patrick’s Cathedral was a who’s who of artists, writers, socialites, celebrities, and surviving members of the original Factory. Haring’s loss was more intimate than what was expressed there in homages by Yoko Ono and Lou Reed. He wrote in his journals that “whatever I’ve done would not be possible without Andy. Had Andy not broken the concept of what art is supposed to be, I just wouldn’t have been able to exist.”

Similarly, thousands, including Mr. Schnabel, Francesco Clemente, Anne Bass, Brooke Shields, and New York’s mayor at the time, David Dinkins, attended Haring’s memorial at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine on May 4, 1990, what would have been his 32nd birthday. Dennis Hopper delivered the main eulogy, tracing Haring’s inspiration to Warhol’s Pop Art and summing up his lasting achievement: “He made his images as common as the Coca-Cola bottle, or Elizabeth Taylor, and yet they were his images. Those images went into the museums and art galleries of the world. And then . . . the next step was to bring it back to the people again . . . so everybody could have art.”

Regina Weinreich is the editor of Jack Kerouac’s “Book of Haikus,” author of “Kerouac’s Spontaneous Poetics,” and co-producer/director of “Paul Bowles: The Complete Outsider.” She lives in Montauk and Manhattan, where she teaches at the School of Visual Arts.

Brad Gooch, a regular visitor to East Hampton, will sign books at the East Hampton Library’s Authors Night on Aug. 10.