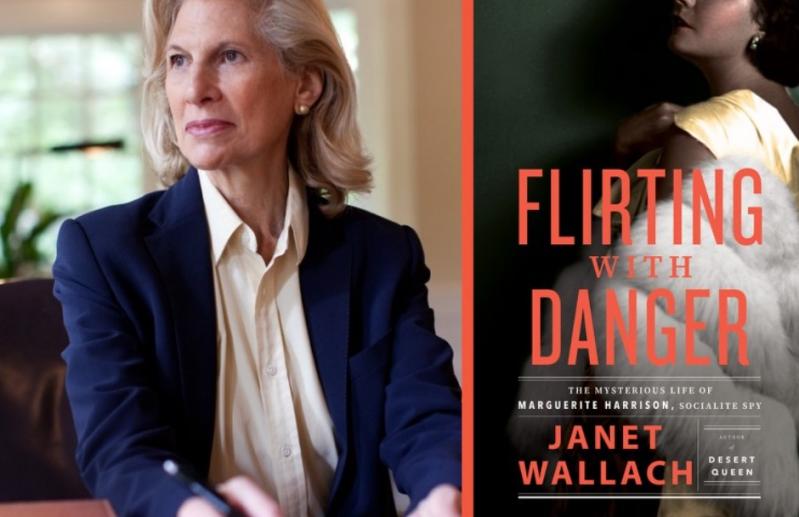

“Flirting With Danger”

Janet Wallach

Doubleday, $30

Hold on to your hats — if you dare to read "Flirting With Danger: The Mysterious Life of Marguerite Harrison, Socialite Spy" you will be in for a wild ride. Janet Wallach takes us from post-World War I Germany, through revolutionary Russia, across the Pacific to Japan, Turkey, Mongolia, and across the Syrian desert to Persia. Marguerite Harrison traveled by car, train, cart, donkey, or on foot, always maintaining an image of glamour and poise. Harrison didn't just flirt with danger, she courted it like a lover.

She was born Marguerite Elton Baker in 1879, to one of the wealthiest families in Baltimore, and spent a privileged childhood sheltered by governesses, educated in private schools. Yet even as a child she was "drawn to adventure, lured by the blurry beyond," and as a young woman traveled extensively with her family, becoming fluent in several foreign languages. At the age of 22, she married a stockbroker, Tom Harrison, gave birth to a son in 1902, and for years enjoyed the domestic pleasures of home and family. But when she was widowed at the age of 37, her domestic life suddenly lost its charm and she turned her attention to working as a reporter, and eventually as a spy.

At the behest of U.S. Army Military Intelligence, she traveled to postwar Berlin under the guise of working as a foreign correspondent, thus becoming the first American woman to enter Germany after the end of World War I. Her assignment was to assess the mood of the German people. How much food and fuel were available? Who was actually in power? Friendly and attractive, she mingled with unsuspecting laborers and socialites, assessed the country's strengths and weaknesses, and reported back to Military Intelligence.

Of course, this type of undercover work was incredibly dangerous. She could have easily been imprisoned or expelled. But when her assignment ended, instead of retreating to the safety of home she barreled headlong into an even greater challenge — a visit to revolutionary Russia. This time she had no visa, no entry papers, no permission to enter the country. Traveling by train, sleigh, and her own two feet, she defied the Russian border guards and entered the country illegally.

Russia was in the midst of a violent revolution. The Bolsheviks were in power, but that seemed to change daily. No foreign diplomats had stayed in Russia; there was no embassy to represent her. If she was caught she was on her own.

For weeks she charmed her way to interviews with government officials and labor leaders, brazenly infiltrated the Kremlin, and even managed a short interview with the Soviet leader Leon Trotsky. When her luck ran out and she was arrested, she was forced to agree to spy for the Soviets, thus becoming a double agent. Eventually she was sent to the Lubyanka prison, where she languished for 10 months in appalling conditions before being released.

Back in New York with her son, she supported him by writing articles and lecturing on life in Russia. But the old ennui returned, this time taking her to the Far East. She started in Tokyo and traveled through Asia to the Far Eastern Republic, land that had been claimed by both Japan and Russia. After such a horrendous experience in Russia, one might think she would steer clear of it. But the Russian people always held a special place in her heart. She had been impressed by their strength and spirit. Amazingly, she vowed to return.

It would be yet another arduous journey, over the Gobi Desert to the city of Urga, across the frozen rivers of Siberia, only to be once again arrested and taken to Moscow and the dreaded Lubyanka prison. After a brief stay, she was released and finally left Russia for good.

Once back in New York, she again felt the same old restlessness, anxious to go "somewhere, anywhere." And so she embarked on yet another adventure — she and two friends would make a film about a "disenchanted Western woman on a search for . . . her ancestral past." They began in snowy Turkey, traveling through Syria and Iraq to Persia. For months they lived in tents, struggling with violent nomadic tribes, crossing turbulent rivers. Even though there was no spying involved, it had all the adventure, suspense, and danger that Marguerite could ever long for.

It might be tempting to dismiss Marguerite Harrison, daughter of the Gilded Age, as a restless dilettante, willing to trade time spent with her son, her father, her friends for adventure, and that might partly be true. But in the last chapter the author shows us that she was much more than that. Each and every accomplishment — author, lecturer, filmmaker, spy — showed her ability as a woman to do anything a man could do and do it well. She was a feminist by action rather than word, and never received the credit she deserved.

And she was a patriot. She risked her life to serve her country many times over.

Her prescience was chilling — she foresaw the ominous rise of antisemitism throughout Germany, observing that "the seeds of the Nazi movement had been sown."

She predicted that Palestine would "never cease to be a battleground of faiths and races."

Through it all she retained a certain glamour. The list of items she traveled with was truly unbelievable — her trusty fur coat, her typewriter, silk stockings, evening dresses, cosmetics, medicines. Did she really travel with a collapsible rubber tub?

The author could have told us a bit less about the adventures making the film, ultimately called "Grass," but then again which adventure could she leave out? The trek across the desert to make a film is a perfect example of a life lived to the fullest, on one's own terms.

From Marguerite Harrison, one would expect nothing less.

Antonia Petrash, a former library director, is the author of "Long Island and the Woman Suffrage Movement." She lives in Glen Cove.

Janet Wallach's previous books include "The Richest Woman in America: Hetty Green in the Gilded Age." She lives part time in Amagansett.