“The Sound of Sleat: A Painter’s Life”

Jon Schueler

Jon Schueler Foundation, $37

“The Sound of Sleat: A Painter’s Life” traces the triumphs and torments of Jon Schueler (1916-1992), a much-lauded abstract painter and the author of this complex memoir, originally published by Picador in 1999. The manuscript, a compilation of journal entries, archival letters, and personal memories, edited by Magda Salvesen and Diane Cousineau, was recently re-released.

Twenty-five years on, Schueler’s musings remain urgent, offering a tome that reveals sentient aspects of the creative spirit, be they desperate, enlightened, or completely maniacal. The book hop-skips from the American Midwest to New York through World War II, Scotland’s Western Highlands, and places in between.

Born in Milwaukee in 1916, Jon Schueler planned to be a writer, receiving an M.A. in English literature at the University of Wisconsin not long before enlisting in the Army Air Corps. Soon after marrying his first wife in 1942, he was dispatched to England as a B-17 navigator, flying missions over France and Germany. His perception of the eternal skies, endless horizon, and mutating cloudscapes are breathtaking — and they pull on his memories of the rain squalls and thunderheads over his native Lake Michigan.

But Schueler’s accounts of the fierce combat, injuries, and horrifying deaths that befell the troops, often his friends, are dramatic in the extreme, portraying an endless nightmare of war in frantic detail. In 1944, he was discharged for combat fatigue. It seems clear to me that he suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder for the rest of his life. Soon after arriving in New York, the couple relocated to Los Angeles, where, two kids later, one day he tagged alongside his wife to a portrait-painting class at the People’s Education Center in Hollywood. And so, his life as a painter began.

Overcoming his awkward artistic dawn, Schueler moved on to San Francisco’s California School of Fine Arts, where he studied with the titans of Bay Area expressionism, including David Park, Elmer Bischoff, and Richard Diebenkorn. He signed up for a class called Space Organization taught by Clyfford Still, an artist whose reputation was formidable. Still arrived late to the first day of class.

Schueler recalled, “Finally he came in. Tall, in a grey, double-breasted suit. Intense eyes peering angrily through steel-rimmed glasses. He stood on a platform and said, ‘The name of this course is Space Organization. I suggest that you organize space.’ Then, he left the room.” He fell under the elder artist’s spell; Still would become a vital mentor and lifelong friend.

Along the way, he introduced Schueler to the art of J.M.W. Turner, whose expressionistic seascapes were a revelation for him. By 1951, he would move to New York City, leaving his wife and daughters behind in California. For this transgression, Schueler would offer decades of written and spoken apologies.

The book ricochets between places and times as Schueler’s narrative bounces from writings of the moment to early memories. While challenging, the confusion does provoke the boiling sense of chaos that dominated much of his life. There are many women, including five wives. His behavior is alternately self-indulgent, brilliant, whiny, and brutal.

But while Schueler was personally unsettled, his career was largely ascendant. By the mid-1950s, Leo Castelli would offer him the very first solo exhibition at his new gallery on East 77th Street. Restless, often self-destructive, and possessed of an unnamable existential dread, he pushed on, painting furiously while contemplating gesture, abstraction, figuration, transformation, and the meaning of it all.

He was fully immersed in the New York art world. His close friends included Mark Rothko, Conrad Marca-Relli, Willem de Kooning, and Ray Parker. Summers were dotted with trips to the Hamptons, where Conrad and his wife, Anita, would host him over long weekends. There, the New York art world could be found cavorting throughout the summer at picnics, dinner parties, and raucous outdoor events.

Of that time, he recalled, “I had many mixed feelings as a result of the weekend — about East Hampton, New York, the meaning of all this frenetic activity, etc. It’s an exciting place to be, in a way — if one is not working.” He continued, “There is a kind of madness going on amongst the artists — as though they’re searching for something — some lost toy — like the wealthy and semi-wealthy of the twenties.”

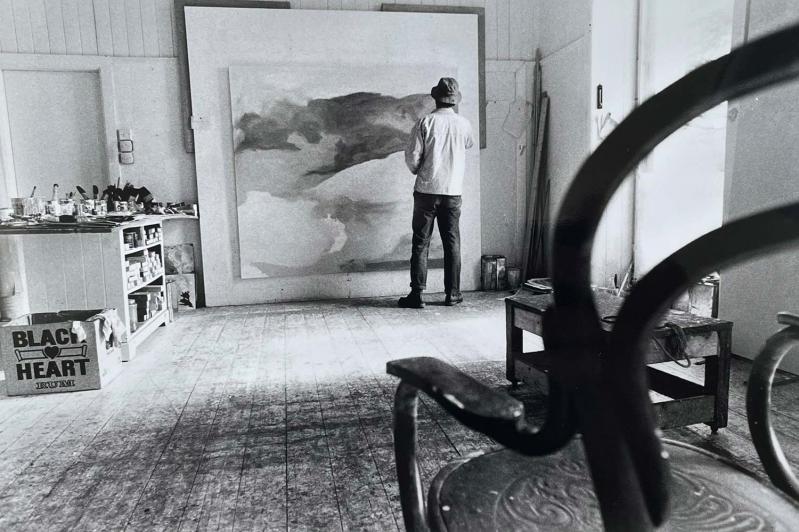

As much as he was an insider, Schueler longed to escape the confines of New York’s urban chaos, at least temporarily, and engage the natural world. In 1957, he embarked on a trip to Scotland in search of a place to lay his brushes and, in a way, find the distinctive subject matter that would provide a structural anchor for his vision. Arriving at the Sound of Sleat, a narrow sea channel between Scotland’s mainland and the Isle of Skye, he found Mallaig, a small fishing village overlooking the Sound. Mallaig would be a retreat for Schueler, who maintained a studio there until his death in 1992.

He was captivated by the sea and sky over the Sound, the peninsula, and the mainland. There, his muses were gales and cloud banks, fog, and the hissing sleet, rain, and snow. “This abstraction of the sea and the sky and Sleat — I was possessed by it, wanted to walk into it, to disappear into it,” he said. “There was not color I could define. . . . The greys were not grey, the silver was not silver, the blacks were not black. It was all light and darkness.”

Schueler spent years skipping back and forth from Scotland to New York to Paris. Different studios, different women, new galleries. But Mallaig continued to call to him. In journal entries and letters, he recounted fishing expeditions on his friend’s trawler, the Margaret Ann. He writes, “To go to sea on the Margaret Ann is to sail into my picture. . . . The storm takes place; the ship moves under me; the mist marries the sea. From the sea, the sky is even more massive, changing, subtle, incomprehensible, than from the land. . . . Are the strange, deep, boundless emotions of death more or less real than the curiously defined events at sea?”

Despite a penchant for melodrama, his gifts as a writer are considerable, and nowhere more pronounced than his recollection of seeing Piero della Francesca’s fresco “The Resurrection” in the town hall of Sansepolcro in Italy. Many have waxed poetic about this stunning work of art, but few have so aptly described its visceral impact. He walked right by the painting before turning around to engage it.

Speaking of the figure of Christ, Schueler wrote, “He was alone in a silent world, alert to his own being, assertive in his stance, erect almost to the point of being arrogant. But arrogance was not necessary. He knew. He knew his power. He knew the drama of the past. He knew of his own willingness to play a part in the drama, and he knew now that the first act was over, and the second long act would begin. No one else knew. Not a soul knew — but God, of course, whose son he knew he was. His face was filled with infinite sadness, of all that he had seen and all that he would ever see, of all he knew.”

Whew.

Galleries would come and go, fortunes would rise and fall, exhibitions and critical acclaim might be legendary, or not. But this aria — this plaintive journey into one man’s grasp of the wordless beauty of a breathtaking work of art — this was at the core of Jon Schueler’s artistic experience.

Janet Goleas is an artist, curator, and writer formerly of East Hampton, now living in Phoenix.

Paintings by Jon Schueler are on view at the Anita Shapolsky Gallery in Manhattan in “Living in the Moment of Abstract Art,” which opened May 16 and runs through Sept. 7.