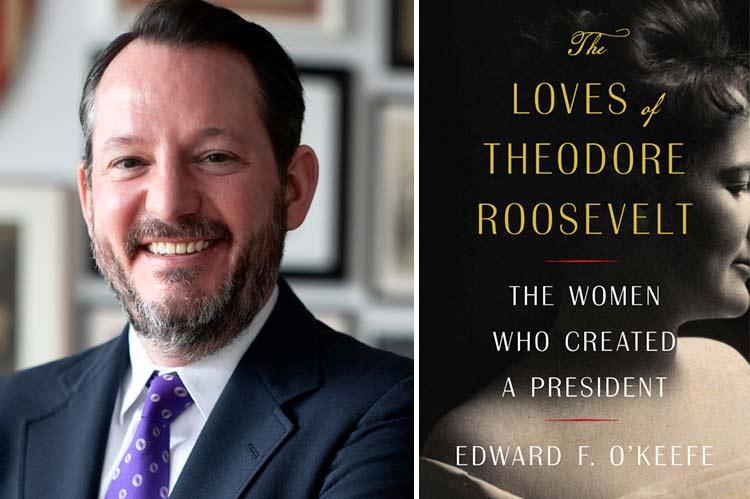

“The Loves of Theodore Roosevelt”

Edward F. O’Keefe

Simon & Schuster, $30

We’ll know we’ve come a long way, baby, when there is no longer a need for books that peer into the distant past to find that women played substantive, if unrecognized, roles on the world stage. That day appears to be a long way off. In the meantime, we have wonderfully readable books in the genre, notably “The Loves of Theodore Roosevelt: The Women Who Created a President” by Edward F. O’Keefe in a debut biography.

The C.E.O. of the Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library Foundation, Mr. O’Keefe reports that he set out to tell the story of Theodore Roosevelt in his Badlands retreat, “a story of resilience” on an American frontier. Born a North Dakotan himself, Mr. O’Keefe had long idolized T.R., as he was known, “one of the most consequential presidents in American history.”

Yet, as he turned the pages of T.R.’s letters, he found that “Theodore Roosevelt was not the impossibly hardy, self-made man of myth and lore,” Mr. O’Keefe writes. “The most masculine president in American memory was, in fact, the product of largely unsung and certainly extraordinary women.”

The ballast that holds the narrative of “The Loves of Theodore Roosevelt” upright is naturally the man himself. But what Mr. O’Keefe has achieved in weaving in the stories of T.R.’s mother, sisters, and two wives is a tightrope walk — particularly given that those women all but shunned a public role and sometimes destroyed crucial evidence of their lives. Indeed, Edith Kermit Carow Roosevelt, T.R.’s second wife, burned virtually all the letters exchanged with her husband.

Through the surviving letters, diaries, and texts, Mr. O’Keefe has put together a portrait of a family that achieved greatness for its hero by leaning into him with passionate generosity. With a glimpse here, a paragraph there, a bold observation that occasionally teeters on the brink of exaggeration, the author renders characters who become as familiar to the reader as beloved cousins. The depth of feeling he ascribes to his players is equally evident in the author himself.

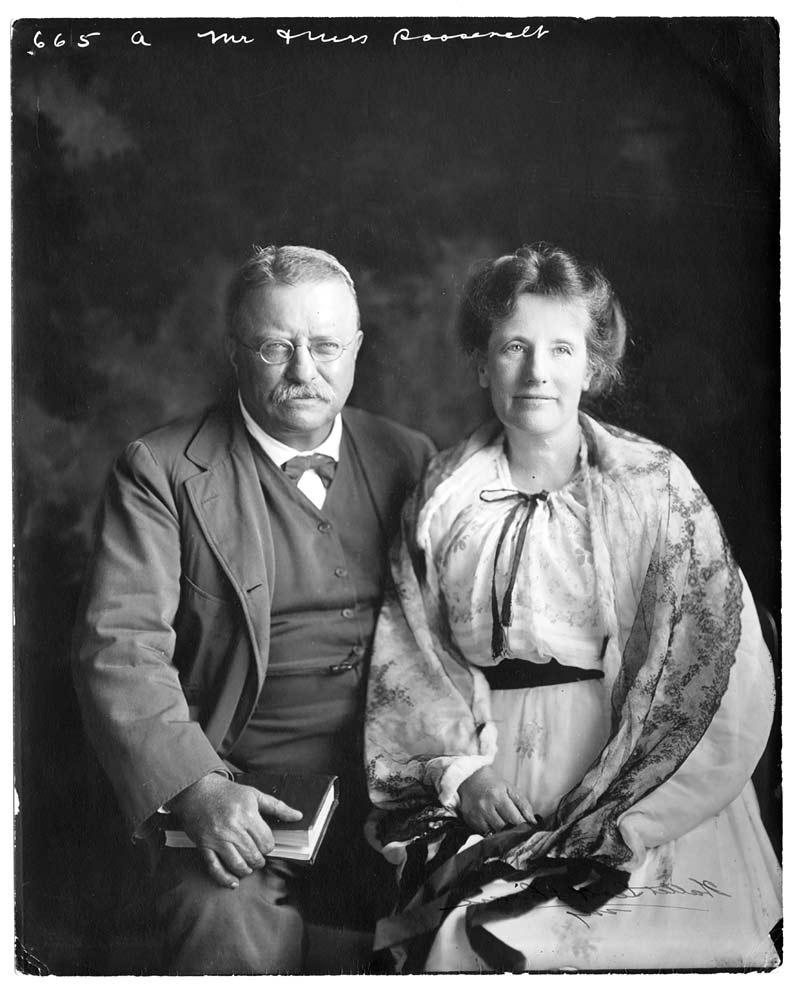

Theodore Roosevelt Collection Photographs, Houghton Library, Harvard College

Teddy was one of four children, born in 1858 to Martha Bulloch Roosevelt (known as Mittie) and Theodore Roosevelt Sr., in a New York City brownstone on East 20th Street. It was the redoubtable Mittie, a Southern belle, on whom it’s rumored the fictional Scarlett O’Hara was modeled.

“She was nothing like the submissively dutiful, Gilded Age stereotype so often depicted,” writes Mr. O’Keefe. She was “tart, sharp-tongued, and witty,” exhorting her children, writes the author, “to live in the moment, forging on through life’s inevitable disappointments and losses.” T.R.’s character, Mr. O’Keefe contends, was closer to that of Mittie than to the father he idolized.

To Mittie the nitty-gritty of motherhood seems to have been of only passing interest. That role would fall to her eldest daughter, Anna, a.k.a. Bamie, senior to T.R. by three years. It was Bamie who hustled up to Harvard to prepare brother “Teedie’s” freshman rooms. As he climbed from the State Assembly to New York City police commissioner, assistant secretary of the Navy, on to governor of New York and, finally, 26th president of the United States, Bamie was his closest strategic adviser.

In New York, Bamie’s apartment became T.R.’s situation room on the fly; later, her D.C. home was the “Little White House” with its revolving door of diplomats and politicians. When the Republican boss of New York State asked for a word alone, T.R. responded, “We shall be quite private except for my sister. I always like to have her present at all my conferences. She takes so much interest in what I am doing.” Bamie was to T.R., Mr. O’Keefe writes in his preface, “what Robert F. Kennedy was to President John F. Kennedy.”

While no such position as political press secretary existed at the turn of the 20th century, his younger sister, Corinne, known as Conie, understood the importance of publicity. T.R. became a fixture in the public imagination during the Spanish-American War, when he resigned his position as assistant secretary of the Navy and joined the legendary Rough Riders in thwarting Spanish forces on Cuba’s San Juan Hill. T.R. put himself directly in the line of fire, “like Lord Nelson defiantly resplendent on the deck of HMS Victory at Trafalgar.” He was dressed as the “perfect khaki emblem” of American masculinity — the showman, always.

Throughout her brother’s career, Conie provided the press with strategic glimpses into his private life.

There are two bona fide love stories in the book. A close friend to the Roosevelt children, Edith Kermit Carow seemed destined to become T.R.’s wife early on. But the evidence suggests that Edie (perhaps harshly) rebuffed his proposal. The details are murky, as T.R. expunged those diary pages. Not long after, the angelic Alice Hathaway Lee captured his attention. His pursuit of her became an obsession, replete with drinking binges and outlandish challenges to duel his rivals. “I did not think I could win [Alice],” said T.R., “and I went nearly crazy at the mere thought of losing her.”

Mr. O’Keefe is a passionate advocate for Alice Roosevelt, T.R.’s first wife, whom he maintains historians have mistakenly cast as an intellectual lightweight against her successor, Edie Carow. It was under Alice’s influence, he points out, that Teddy “embraced women’s suffrage,” a position, ironically, not shared by his sisters. Teddy’s astonishingly radical senior thesis at Harvard, “Practicability of Giving Men and Women Equal Rights,” argued that equal rights for women were not only moral and just but wholly self-evident.

“It is doubtful if women are inferior to men . . . individually many women are superior to the general run of men,” wrote Teddy, and “as regards to the laws relating to marriage, there should be the most absolute equality preserved between the two sexes.” It’s hard to imagine Teddy, a man of his day, embracing feminism without Alice’s prodding. “If we could once thoroughly get rid of the feeling that an old maid is more to be looked down upon than an old bachelor,” he continued, “or that woman’s work, though equally good, should not be paid as well as a man’s, we should have taken a long stride in advance.” Right on.

Married to Alice, Mr. O’Keefe writes, T.R. “rose like a rocket,” winning a term in the New York State Assembly. Tragically, on Valentine’s Day three years later, she died of kidney failure following the birth of their daughter. (Mr. O’Keefe includes the heartbreaking poem “Annabel Lee” by Edgar Allan Poe, whom T.R. admired, which reads eerily almost as if it had been written for the occasion.) Later that night, T.R.’s mother, Mittie, succumbed to typhoid fever.

A felled bull in the ring, T.R. turned down an invitation to run for a fourth term in the Assembly — “the light has gone out of my life,” he wrote in his diary. He retreated to the Badlands, persuaded that for him any meaningful life was over. Years later he claimed that he would never have become president without his time as a cattle rancher in North Dakota.

Back in New York, it was Bamie, of course, who took care of baby Alice (Alice Roosevelt Longworth). In good time, she orchestrated a “chance” meeting with T.R.’s childhood sweetheart, Edith Carow, whom he wed in spite of an expressed disapproval of second marriages. If Alice was “sunshine,” the author contends, then Edie was a “cloudy day.” Described by one observer as “almost Oriental” in her detachment, her devotion to T.R. was absolute; her jealousy of those who commanded his attention — as well as the specter of his first wife — encouraged his family to step lightly in her company.

As first lady, Edith was frequently in the rooms where it happened, so to speak, knitting quietly in the corner. President Roosevelt continued to take advantage of “the sexism of the time” to keep the women he relied on close at hand. “Her judgment of men was nearly always better than his,” Henry Stimson, a Roosevelt crony, wrote of Edie. “Her influence was freely exerted on him and whenever I saw it it was in the direction for good,” he continued.

Teddy admitted, “whenever I go against [Edith’s] judgment, I regret it.”

On the night of the 1904 presidential election, T.R. claimed that win or lose he would have no complaints. “Infinitely more important [is the] fact that I have had the happiest home life of any man I have ever known.” Edith would bring the role of first lady into modern times, creating the White House’s executive West Wing, its Rose Garden, and the portrait gallery of first ladies. She made the White House musical evenings a thing — an innovation that is typically credited to the more dazzling Jackie Kennedy.

It was a love story to the end. In a letter to his son Kermit, he wrote of Edith: “[She is] as charming and bewitching as ever; & all her ways are so attractive. . . .”

While Mr. O’Keefe may romanticize the Roosevelt family, he has no illusions that they lived in better times. The Gilded Age and its aftermath were rife with corruption, self-serving party bosses, greedy entrepreneurs, anarchist plots, and megalomaniacal politicians, T.R. withstanding. “My father always has to be the bride at every wedding and the corpse at every funeral,” quipped his daughter Alice, a legendary wit.

Yet there was less daylight between conservative and liberal positions. A Republican in name, T.R. stood for conservation, child labor laws, public education reform, urban housing codes, and the nation’s first pure food and drug laws. He fought political corruption and corporate interests, being “vehemently opposed to wealth made on the backs of ordinary people.”

“The Loves of Theodore Roosevelt” will make its readers disheartenedly conscious of the thin political gruel that’s served today and long for the kind of a public servant for whom courage is the mark of character.

Ellen T. White is the author of “Simply Irresistible,” a book about the great romantic women of history, and the forthcoming “Key West: Paradise Found.” She lives part time in Springs.

Edward F. O’Keefe has a house in Bellport. Theodore Roosevelt’s “summer White House,” Sagamore Hill, is in Oyster Bay.