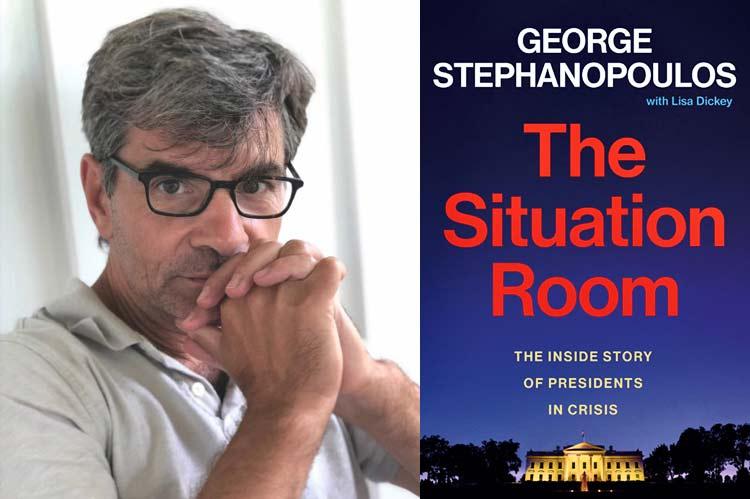

“The Situation Room”

George Stephanopoulos with Lisa Dickey

Grand Central, $35

It is far more than four walls within which history is shaped.

The underground White House Situation Room is a continuing operation, regularly modernizing and expanding, with special mission, manpower (womanpower as well, of late), and mystique matched only by the Oval Office.

For George Stephanopoulos, the former Clinton White House communications director now ABC-TV anchor, the Sit Room also provides fascinating access to inside views from more than 50 years of key White House foreign-policy decisions — some successful (resolving the Cuban Missile Crisis, bombing for peace in Bosnia, eliminating Osama bin Laden), others not so much (a failed effort to free U.S. hostages in Tehran, chaotic withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan).

Cycles of recent history also come clear: the rise, fall, and rerising now of Cold War with Moscow, continuing challenges from Iran and its various militia and terrorist proxies, and wider instability caused by hot conflict between Israel and its Arab neighbors.

In “The Situation Room” Mr. Stephanopoulos also spotlights lower-level personalities involved, little-known staffers — veteran intelligence, military, security, and diplomacy experts rotating in from posts throughout the government — all determinedly apolitical as they track international crises from official sources and outside (often swifter) news media — striving to create balanced assessments and the quickest possible communications.

So loyal, too, they refused to evacuate on 9/11 as passenger jets commandeered by Al Qaeda terrorists plowed into New York and nearby Washington, D.C.

Their interviews are particularly important because, despite ever-advancing technology, there are few recordings of top-level Sit Room debates and presidential phone calls. Staffers with security clearances higher than their typing skills produce transcripts on the fly. Why? “Plausible deniability,” argues one veteran of the process. “Somebody in the Sit Room misunderstood.”

The “room” itself, actually an “underwhelming” complex of small rooms at the start, was born of disaster. Embarrassed by the C.I.A.’s misbegotten invasion of Cuba’s Bay of Pigs in 1961, President John Kennedy seized on the suggestion for such an intelligence and communications center passed to him just 10 days before.

With an early-version fax machine, pneumatic tubes to circulate news and analyses, and “the occasional rat and cockroach skittering through,” the Situation Room would first “prove its true worth” in the next set-to over Cuba — tense strategy sessions over the Missile Crisis of 1962. At the end, knowing the delays in normal diplomacy, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev announced his decision to remove rockets in a Radio Moscow broadcast, routinely monitored by the C.I.A.’s Foreign Broadcast Information Service, into which the Sit Room was plugged.

Unmentioned in this book, perhaps because it was also too secret even for the Sit Room at the time, was the deal that prompted the Red withdrawal. As secretly proposed to Russia by U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy, the U.S. would in turn later remove its Jupiter missiles from neighboring Turkey.

J.F.K himself mostly visited the Sit Room to read newswires. After the assassination, Lyndon Johnson “was there all the time.”

Accordingly, the space expanded both physically and technologically. And because Johnson also introduced widespread taping of his conversations (a practice Richard Nixon lived to copy and regret), many recordings show the president’s growing doubts, desperation, and depression over the Vietnam War, which he could not resist micro-monitoring, though “body counts couldn’t tell him the war was being won,” Mr. Stephanopoulos sympathizes.

Taping aside, Nixon did not adopt L.B.J.’s affinity for the Sit Room, “the melodramatic idea that the world could be managed, in crisis” there, sneers Henry Kissinger, who led most Sit Room meetings as national security adviser, then secretary of state. The historian Garrett Graff also sees Nixon feeling the Sit Room staff “were all enemies.”

On Oct. 24, 1973, with Israel at war with Syria and Egypt, their ally Moscow was sending warships with nuclear weapons to the region. Nixon, we are reminded, was “distraught” over eight impeachment resolutions just filed against him in the House, and likely drinking. (The president was “loaded,” Kissinger reported days earlier, nixing Nixon taking a call about the Mideast war from Britain’s prime minister.)

So though White House Chief of Staff Al Haig ran messages up to Nixon from the Sit Room, and issued directives, there is no solid evidence of actual Nixon input. “Al Haig was the president,” says a former National Security Council staffer, William Lloyd Stearman. Later, as Ronald Reagan’s secretary of state, Haig ruffled feathers by actually claiming he held “the helm” after the president was wounded and V.P. George Bush remained in flight to Washington.

Like Nixon, Donald Trump had little presence in the Sit Room — because he knew everyone there “knew a lot more than he did,” suggests John Bolton, one of his four national security advisers. “Basically, he’d parachute into policy every now and then and throw a hand grenade,” said the N.S.C. European affairs director, Alexander Vindman, whose report on the infamous “investigate Biden” call with Ukraine’s Volodymyr Zelensky led to Mr. Trump’s first impeachment.

Wake-up calls are always an issue for the Sit Room. Twelve days after the ignominious fall of Saigon, Cambodian forces captured the U.S.-flagged cargo ship Mayaguez with 39 American crewmen at 3:18 a.m. Washington time. It took two hours for word of it to reach the Sit Room, and it wasn’t until 7:30 that staff there relayed it to the deputy national security adviser, Brent Scowcroft, who told President Gerald Ford within minutes. Kissinger was furious over being informed only at his regular 8 a.m. briefing.

Plans for a counterattack were soon underway. But far faster communications permitted a U.S. pilot to pass word of a possible Mayaguez hostage on the deck of a Cambodian fishing boat he’d been ordered to destroy. In the Sit Room, Kissinger argued to attack it anyway to give “the impression that we are potentially trigger-happy.”

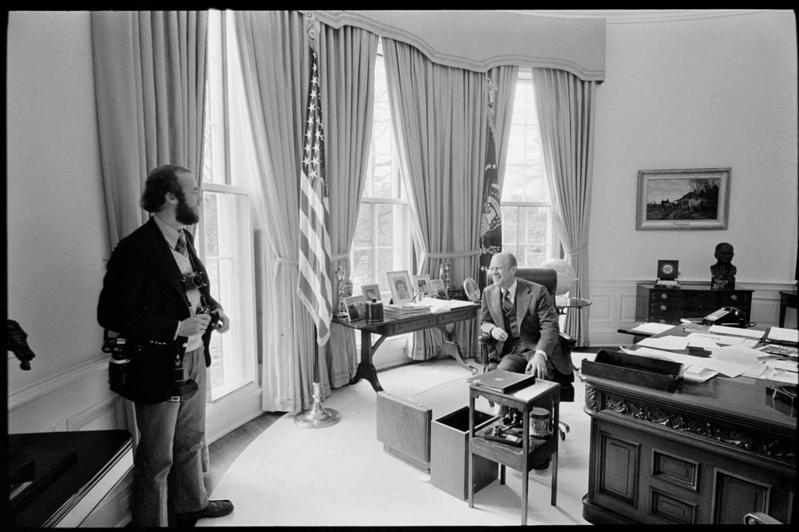

Ford overruled that idea (hostages were later found aboard) but he agreed with Kissinger on punishing the Phnom Penh regime by “fiercely” bombing the mainland. Then came an unprecedented Sit Room interruption — by the White House photographer.

“Has anyone considered that this might be the act of a local Cambodian commander who has just taken it into his own hands to halt any ship that comes by?” challenged the 28-year-old David Hume Kennerly, already a Pulitzer winner for his Vietnam coverage. “I was in Cambodia just two weeks ago and it’s not that kind of government at all.”

Ford took heed, called off a massive B-52 strike, and later advised Mr. Kennerly: “Next time you’re going to speak out, just hand me a note.”

Americans taken hostage at the U.S. Embassy in Iran in late 1979 were the Sit Room’s top priority for months, and the ultimate undoing of a re-election bid by Jimmy Carter, who even sought help from a Pentagon program testing psychics.

As negotiations stalled, and against the advice of Secretary of State Cy Vance (who said he would have to resign, and did), Carter decided on a risky rescue mission, doomed by insufficient information and observation of a desert rendezvous site for U.S. troop transports, helicopters, and more than a hundred men — 200 miles from Tehran.

After an unexpected zero-vision dust storm, mechanical problems for too many copters forced the order to abort. But a fiery crash on the ground between one copter and a transport still left eight Americans dead, their charred bodies subsequently displayed as “war trophies.”

The Sit Room apparently also was unaware that former Texas Gov. John Connally was touring the Middle East extensively in 1980 to spread word that Tehran would get a better deal by holding the Americans until Ronald Reagan officially became Carter’s successor — just what Tehran did.

The Desert One disaster haunted the Sit Room and all those tasked with carrying out Barack Obama’s 2011 order finally to capture or kill the Al Qaeda founder-in-hiding Osama bin Laden. Once the C.I.A. identified a likely bin Laden courier, satellite tracking led to a suspiciously large compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan.

Inside, a tall man who walked in circles around the walled-in yard was dubbed “The Pacer.” The probability he really was bin Laden, as reported in the Sit Room, ranged from only 40 to 60 or 70 percent. But not acting was not deemed an option.

Vice Adm. William McRaven, head of the Joint Special Operations Command, reported his determination and preparation to avoid past errors in a proposed raid on the bin Laden compound — including live camera views, extra copters on standby (one copter did crash inside the compound), and many end-to-end rehearsals on a life-size mock-up.

The biggest surprise for Mr. Stephanopoulos was learning he himself had a role in the successful bin Laden decision. In a final Sit Room debate, Defense Secretary Robert Gates opposed the raid, preferring a safer drone attack. But when his undersecretaries, Michele Flournoy and Mike Vickers, risking their jobs, privately re-argued the case with him and “changed my mind,” he then alerted the White House.

Something Mr. Stephanopoulos had told Ms. Flournoy decades earlier, about relaying unpopular views, helped motivate her, she told him: “The job of a political appointee is to tell the boss what they need to hear, not what they want to hear.”

Not a bad credo for all those in the Situation Room confronting the crises to come.

David M. Alpern was a writer, senior editor, and radio host for Newsweek magazine over 40 years, with George Stephanopoulos among his guests. He lives in Sag Harbor and on June 29 will produce “Best of the Versed,” a night of cabaret at LTV Studios in Wainscott.

George Stephanopoulos lives part time in East Hampton. “The Situation Room” comes out on May 14.