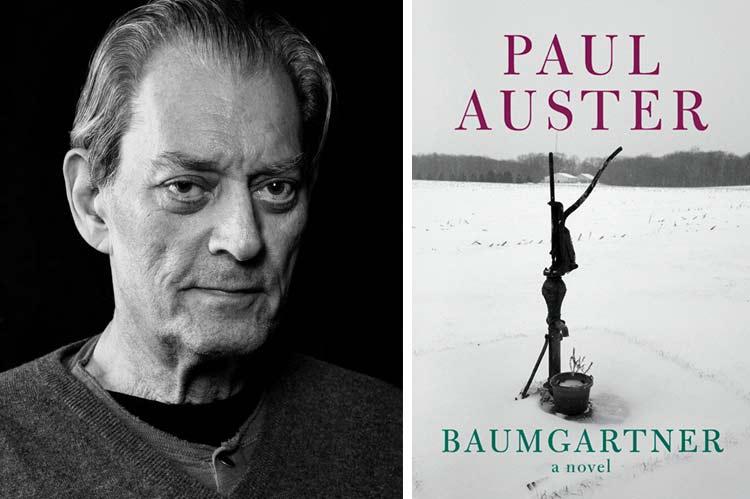

“Baumgartner”

Paul Auster

Grove Press, $27

In his final novel, "Baumgartner," Paul Auster draws readers from the present to the past with brilliant back stories.

With its connections to youth and stories of the 1960s, in just over 200 pages "Baumgartner" achieves an incandescence not unlike that in "The Red Notebook," Auster's collection of intertwined essays on his years growing up. Baumgartner means "tree gardener" in German, and Auster, who attended Columbia High School in Maplewood, N.J., a little over 20 miles west of his last home in Brooklyn, has an affinity for leafy, suburban neighborhoods.

Auster brings Baumgartner, the character, to life as a widower, a soon-to-retire professor of philosophy who has taught at Princeton University. Baumgartner lost his wife, Anna, nine years earlier, when she suffered a broken back and drowned while swimming in large surf off Cape Cod, where the couple visited friends.

Auster peppers Baumgartner's remarks with colloquialisms of the past, describing Anna as a "crackerjack swimmer to boot," for example. Baumgartner has struggled to recover from this loss, and while still grieving he sorts through reams of Anna's poetry and translations to not only learn more about her early life, but also to edit and compile a posthumous collection of her verse.

As Baumgartner excavates the work of his lost wife, he comes upon a typed journal held together by a rusty paperclip. Anna's first-person prose begins with a section on Frankie Boyle, whom she met in the sixth grade, "a lean and young gentleman of impeccable virtue," before he moved on to a Catholic school and she to the public high school in Livingston, N.J.

But at 17 she sees him working at his father's gas station, and they begin a love affair as America plunges deeper into the Vietnam War during the tumultuous years of 1967 and 1968.

"It was in the midst of all those roiling messes that Frankie and I latched on to each other and had our one brief fling, in the weeks between the murder of Bobby Kennedy and the end of high school, precisely four desperate but delicious all-naked love binges in the back seat of my mother's Buick, which we parked deep in the woods . . . where not even the owls could see us."

Auster captures the generational divide as Frankie, "to spite his father," enlists in the Army and hopes to benefit from the G.I. Bill. Frankie's decision is likely to disappoint the reader, who at this point in the story is rooting for Anna and Frankie, as he burns with a passion for a better life.

But far from the jungles of Vietnam, "during a basic-training exercise at Fort Dix . . . a rocket launcher misfired and blew up in his hands," thus scattering Frankie Boyle to smithereens. With this loss Auster effectively hits readers, too, as he characterizes the Vietnam years in America as a sort of breakdown into insanity.

Baumgartner learns that when Anna heard "what had happened at Fort Dix she sat in her freshman dorm room at Barnard and sobbed her heart out for ten straight hours, sobbing as she had never sobbed before and never would again." Such grief, Baumgartner notes, "comes close to destroying you" and cannot be endured "more than once in a lifetime."

Anna's loss extinguishes her own youth, too.

Years later, sitting in Anna's study, Baumgartner misses the music of her hands at her manual typewriter's keys as if she were playing music. These back stories tell a tale rich in 20th-century American history, a history some Americans lived through, while younger readers may have only read about — either way, a gift.

Significantly, "Baumgartner" includes not only a back story of the Vietnam War years, but also one of an immigrant family from the former Austro-Hungarian Empire, where Jewish culture once thrived before near total extinction in the Holocaust, and thus the novel resonates more deeply.

While "Baumgartner" plumbs fascinating depths in excavating the dusty cellars of back story, it also involves at least three accidents as the narrator writes a book on loss and phantom-limb syndrome. In one, a utility worker rescues Baumgartner after a bad fall, as once again coincidence and luck, both bad and good, appear in Auster's work. The willingness of the man to help old Baumgartner brings a light of hope into the darkness. It's the sort of rescue he could not extend to his wife. Similarly, Anna could not protect her childhood friend, Frankie.

Nine years after Anna's death, Baumgartner embarks on a series of dalliances, even traveling "once as far as Shelter Island, a blob of land between the North and South Forks of eastern Long Island." He demonstrates American gumption, and enjoys using the American vernacular, which helps illustrate his resilience as he attempts to rebound but inevitably returns to dwelling on Anna and her death.

Ironically, Baumgartner's loyalty to Anna's memory helps him emerge from his darkness. The brightest moments in Auster's novel occur in the past, in memory, and in explorations of Anna's history, which even her surviving husband cannot fully comprehend until he reads it for himself and digs backward.

A young woman, a scholar at the University of Michigan, contacts Baumgartner and expresses an interest in Anna's poetry and wishes to do research on her unpublished manuscripts. This connection back to Anna inspires him to hire gardeners to tidy his yard and carpenters to convert an apartment over the garage for this scholar to live in while she completes her research.

Anna, however, remains at the center of Baumgartner's life, even though she died nearly a decade earlier, and his searching and remembering leads to an unexpected yet convincing conclusion to the novel.

Daniel Picker is the author of a book of poems, "Steep Stony Road," and his prose has appeared in Harvard Review, The Sewanee Review, and The Georgia Review.

Paul Auster, a past visitor to the East End, died on April 30.