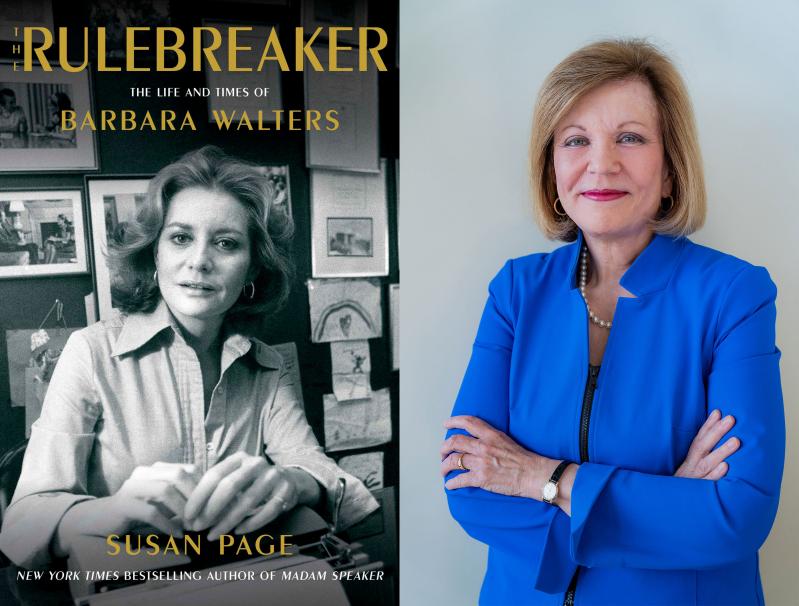

“The Rulebreaker”

Susan Page

Simon & Schuster, $30.99

It was a TV news trifecta. In November of 1977, for the first time ever, a leader of Egypt, Anwar Sadat, was flying to Israel to talk about peace. And all three major U.S. networks competed to cover it.

CBS sent the veteran evening anchor Walter Cronkite. NBC sent his counterpart, John Chancellor. And third-place ABC sent Barbara Walters, already famous for breaking from a traditional girl-writer’s role to do high-profile interviews at NBC’s “Today” show, then for becoming the first-ever female evening news co-anchor at ABC, its “Million Dollar Baby,” the cost split — tellingly — between its news and entertainment divisions.

Cronkite had filmed an interview with Sadat before and arranged for another in Israel. So had Walters, and one with Israeli leader Menachem Begin, who soon delighted her with a little surprise, as recounted by Susan Page, USA Today’s prizewinning Washington bureau chief, in “The Rulebreaker,” a fascinating new biography full of surprises even for dedicated Walters watchers.

“On the ride from the airport,” Begin told her, “I said to President Sadat, ‘For the sake of our good friend Barbara would you do the interview tomorrow with me together?’ ” Sadat had already rejected that request from Walters herself. But now, “Barbara, Sadat said yes,” Begin enthused.

Indeed, their first-ever joint interview began with banter about how pretty Walters was. Then Sadat kissed her.

Not that he would speculate on how peace could actually be negotiated. “Barbara, politics can’t be conducted like this,” he admonished, with Walters responding: “I have to keep trying.”

Cronkite quickly arranged his own interview with both leaders for later in the day, after which he was heard on the satellite feed asking, “Well, did Barbara get anything I didn’t get?” Was he told about the kiss? Ms. Page does not say. Would he have cared?

Chancellor’s joint interview came only the next day, after which NBC had to issue a statement that he had not been dressed down for being last. Two weeks later he confirmed he would vacate the anchor desk to be a network commentator.

It was groundbreaking TV for a worldwide audience, and a huge step toward recovery for Barbara after low ratings had bumped her from that ABC anchor desk, previously vacated by her co-host, Harry Reasoner, who clearly disdained her sharing his spotlight.

“The interview put me back on the map as a serious journalist,” Walters said. “From that time on I was more or less accepted as a member of the old boys’ club.” And her list of top newsmaker interviews after she moved to “20/20” (about the time of my studio visit with her, if memory serves) and much ballyhooed specials cannot be dismissed: Cuba’s Castro, Syria’s Assad, Russia’s Putin, and so many more.

She worked fiercely to line up her V.I.P. guests, sometimes stealing them away from correspondents at rival networks, or more rudely, her own. Then she tirelessly researched, wrote, and rewrote her trademark probing questions on cards easily shuffled to follow the course of each conversation.

Not about to restrict herself to the old boys’ who, what, where, when, and why, Walters became a critical catalyst in the evolution of TV news — for better and worse. She personified the introduction of showbiz touches and talent that increasingly dominate today’s Infotainment Age, with interviews that included riding on the back of Sylvester Stallone’s motorcycle, powerboating with TV’s Don Johnson, teasing Ronald Reagan about the “scroungiest” jeep at his ranch.

Even for her most watched interview — with an estimated 70 million viewers, the most watched of any TV interview ever, Ms. Page maintains — Walters had to gild the lily. For a March 1999 broadcast, the set was made to look like a living room, with upholstered couch, shelved sets of leatherbound books, even a faux fireplace, for an unintended newsmaker whose place in history rested firmly on a previously reported quest for “presidential kneepads.”

Yes, after much personal persuasion by Walters and some controversial financial arrangements, came the first-ever interview of former White House intern Monica Lewinsky, whose big news was “yes” — oral and digital intimacies with Bill Clinton left her “gratified,” as Walters delicately put it.

“Despite the lack of details, that certainly sounded like sex,” Ms. Page writes, though guys in the locker room might well see only third base. Mr. Clinton had by then survived impeachment and won a second term.

Walters made waves, of course, but a larger current was already moving that way. Many think that once Don Hewitt’s “60 Minutes” on CBS showed news could make money, it suddenly had to, competing with and learning from onscreen entertainment.

“People are interested in many things that are not intrinsically important,” Ms. Page quotes an internal memo by William Sheehan, the ABC News president at the time. “I want more stories dealing with the pop people. The fashionable people. The new fads. Bright ideas. Changing mores and moralities.”

Walters was clearly a solid bridge to that goal, but surprisingly never as confident about it as she appeared, Ms. Page repeatedly reminds us. Which led to private pain over the endless Baba Wawa riffs spawned by “Saturday Night Live.”

Keystone Features/Hutton Archive/Getty Images

It was in large part a daddy thing. Lou Walters of Latin Quarter nightclub fame — and cyclical financial flameout — kept his family on a repeating roller coaster between comfortable wealth and financial desperation. Walters could never feel sure her own success would last, leaving her endlessly driven to prove herself anew.

Of course life with father provided backstage familiarity with celebrities and connections that might later help her career. But he also set the model for putting career above family and for the type of men to whom Barbara was later attracted — a certain swagger, not always permanently successful. This included two of the three men she divorced and one from whom she accepted an engagement ring, perhaps Ms. Page’s biggest surprise, Roy Cohn.

Gossip columns called it dating. At least he fed her useful gossip, we learn, while she lent him respectability offsetting his weaselly image, storied mob connections, and service to red-baiting Senator Joseph McCarthy. She stood by him in the AIDS crisis.

After three Walters miscarriages, Cohn also facilitated the 1968 adoption of a newborn by Barbara and her then-husband, Lee Guber, a theatrical producer. “Congratulate me, I just became a mother, of a baby girl,” Barbara proclaimed to the Chicago Tribune reporter with her when the confirming call came (the late Carol Kramer, my first wife, though she never mentioned it).

Perhaps unwisely, Barbara named the child Jackie, after the developmentally challenged older sister about whom she long harbored mixed feelings of anger and guilt. And with her career foremost, “the imperative for a parent to be present was something she never seemed to understand or accept,” Ms. Page writes, describing Walters as “perplexed and disappointed” that the little girl did not share her passion for fashion, breaking news, New York — and later increasingly troubled, troublesome, drug-prone.

It was all the young women Walters inspired to enter and remake journalism that she touted as “my legacy” — or at least more than two dozen of them, from Diane Sawyer and Robin Roberts to Katie Couric and Paula Zahn, who gathered to mark her 2014 retirement at age 84.

It was on an episode of “The View,” which Walters also helped develop, attracting and inspiring an older generation of women. And it was with that ever-shifting all-female panel that Barack Obama chose to make the first presidential appearance on daytime TV. “I was trying to find a show that Michelle [the first lady] actually watched,” he joked then.

Unfortunately, the good feelings about her legacy did not last. Slips she had been making on the air toward the end, prompting colleagues and friends to urge her final sign-off, were not signs of dementia (as had plagued her late mother) but rather physical brain damage, Ms. Page reveals — hydrocephalus, water on the brain — from tumbling down grand steps at the British Embassy the night before Mr. Obama’s inauguration, likely because of a fever.

Cognitive decline continued despite delicate surgery. Self-isolated in her posh Fifth Avenue apartment (now listed for $17 million, down from an initial $19 million), increasingly unlikely to recognize the few invited, she was unaccountably “unhappy about how she never got her due,” one former colleague tells Ms. Page, and resentful of so many women who had the benefit of her footsteps to follow.

Friends with and without newspaper columns maintained a much more upbeat cover story until her death in 2022 at age 93. The artifice would likely not have bothered even a more aware Walters, whose dedication to truth did not always apply to her own private life. In a college application essay, Ms. Page discovers, she seemed to borrow the summer stock theatrical experience of a high school classmate. Arguably TV’s foremost interlocutor, she hated being interviewed herself.

The plaque at her gravesite in Miami says simply, “No regrets. I had a great life.” But some years earlier, Ms. Page reports, a more candidly reflective Walters confessed: “Most of the time when I look back on what I’ve done, I think, ‘Did I do that?’ And you know what I say to myself? ‘Why didn’t I enjoy it more?’ ” Sad.

Barbara Walters was a part-time resident of Southampton Village. In 2014 she received a Lifetime Achievement Award from East Hampton’s Guild Hall Academy of the Arts.

David M. Alpern reported, wrote, or edited at The New York Post, The Daily Journal of Elizabeth, N.J., United Press International, and Newsweek magazine over 60 years, running the “Newsweek on Air” and “For Your Ears Only” network radio shows for three decades. He now interviews authors for libraries near his home in Sag Harbor.