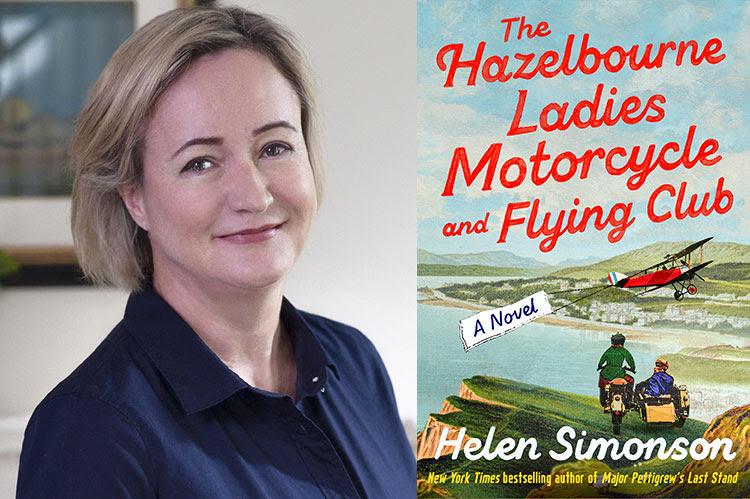

“The Hazelbourne Ladies Motorcycle and Flying Club”

Helen Simonson

Dial Press, $29

Attention, fans of historical romance: The sun is hot, the umbrellas are shading, and I don't have to tell you that summer won't last forever. Here's a history fix synchronized with this novelistically cherished season, spinning out until "a chill in the air as afternoon lengthened into evening" spells fall in the narrative and "The Hazelbourne Ladies Motorcycle and Flying Club" ends with a swelling sort of feel-good upswing.

On the whole, spoilers are not at issue here — I think reading Helen Simonson is something like reading Jane Austen, plot-wise. It's a romance, it's not going to not be a romance: We know where we're going, and that does not stop us from engaging with getting there.

That said, I'm still always a little surprised when Marianne winds up with Colonel Brandon in "Sense and Sensibility," and in the novel at hand, more than one character is introduced who might present tall, dark, and handsome with competition in the love interest department, creating a subtle play of possibility that helps to deflect any sense of predictability.

Ms. Simonson ("The Summer Before the War," "Major Pettigrew's Last Stand") has come forward with organized prose and a fine-tuned setting just poised to host a well-drawn protagonist making her way through catalyst, action, climax, and resolution.

The scene is the Meredith Hotel in Hazelbourne-on-Sea — the British seaside — in the summer at the close of World War I. Proper dress and comportment and appropriate chaperones are required for young ladies taking tea. Also eating lunch, attending dances, and making any move at all in the picky, standard-upholding eyes of the hotel patronage and staff. Ms. Simonson maximizes the possibilities of this backdrop to outline the struggles, across class, of women seeking independence and autonomy in an emerging postwar climate.

Enter Constance Haverhill, earnest, capable, honest with an edge to her sense of humor. We know she's pretty because of how people react to her, and we know she's smart because of what she says. A farmer's daughter with no means, she has lost her position managing an estate (bolstered by correspondence courses in accounting) as men coming home after armistice reclaim positions at the expense of women who stepped in to work during the war years. Constance has one summer in residence at the hotel as a companion to a wealthy friend of her family, and then, she knows not what.

Klaus, a German-born waiter at the Meredith Hotel who is suffering his own postwar experience of bias and exclusion, shakes his head: "A young woman with no dowry, in need of a husband? She was both a fresh new topic and a very old story, at once as unique as a snowflake and as common as a pebble on Hazelbourne beach."

Thus, the clock ticks on Constance's fortunes and a certain tension is established as the plot unfolds in careful, logical increments, scaffolded by the events of one summer. At the hotel, Constance bumps paths with a brash, convention-busting daughter of privilege, Poppy Wirrall, who runs the titular Hazelbourne Ladies Motorcycle Club and also a motorcycle sidecar taxi service, and has dreams of establishing a ladies flying club as well. She harbors and employs women, leveraging her class status and resources to shake social mores and champion the stubborn matter of social mobility.

Constance is pulled into Poppy's dual circles of renegade women from the motorcycle club on one hand, and young ladies and gentlemen of wealth on the other. The latter set includes Poppy's (tall, dark, and handsome) brother, Harris, a fighter pilot whose leg was amputated in the war and who has returned with a sharp tongue, justifiable depression, and a surprisingly lyrical death wish. He faces discrimination around his disability cloaked in genteel indulgence and exhortations to retire as a country gentleman.

Ms. Simonson draws the sibling relationship between Poppy and Harris as part savage rivalry and part tender devotion, showcasing her command of relatability. The relationship is animated as background to plotting around the rebuilding of a devastated Sopwith Camel in the barn on the family estate. A pressing deadline creates urgency, followed by the development of who gets in the cockpit with whom. Meanwhile, never mind that the Sopwith Camel is the very model of machine with which Harris gained flying expertise, and alas, the very model that took him down. The obvious metaphor is all business, constructed to support the plot by a skillful practitioner.

Class consciousness, gender expectations, attitudes toward disability, racial prejudice (appearing in a subplot), and xenophobic bias emerge and make points on the page as the book moves to the crescendo of a Peace Day celebration in which the entire cast of characters plays a part. There's a parade involved. Also a battle re-enactment, and a fancy dress party at which fates may or may not be decided.

Though the historical details and the clearly drawn outlines of the social struggles of women at the close of World War I in England hold interest, it's Ms. Simonson's expert scripting of romance across 400-plus pages of summer that truly fuels the book. If there was a dexterously written and extremely well-timed kiss (that I was waiting and hoping for!) between a handsome, wounded fighter pilot with an attitude and a pretty, capable girl with an uncertain future, I for one read the scene over at least three times, savoring the fact of this kind of fiction: that love wins the peace.

In the satisfying rightness of the world of this novel, it has won the whole darn war.

Evan Harris is the author of "The Quit." She lives in East Hampton.

Helen Simonson lives in Westhampton Beach.