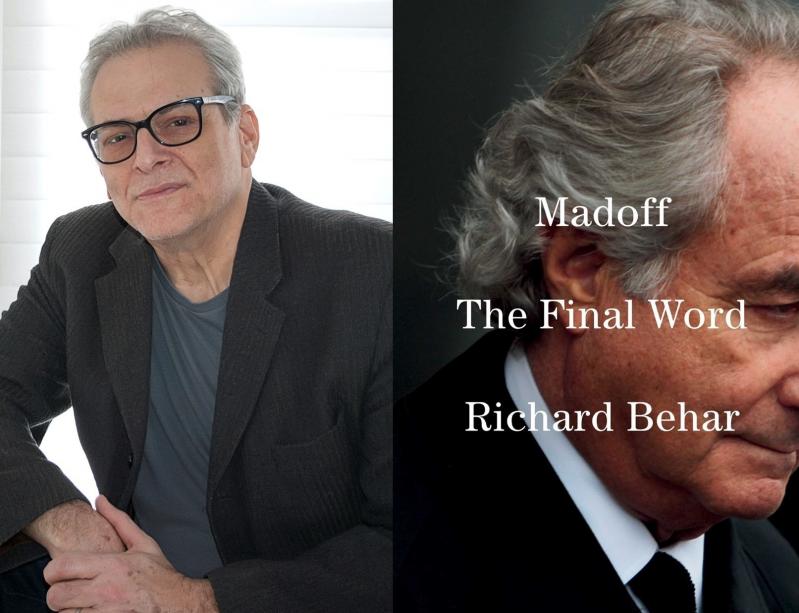

“Madoff: The Final Word”

Richard Behar

Avid Reader Press, $35

Bernie Madoff: "Now all of a sudden everybody is upset."

Now was Dec. 11, 2008, when "his then-active 4,900 client accounts . . . had an estimated $68 billion of assets on paper," all of them fake. This was the greatest Ponzi scheme in history, and it lasted — undiscovered — for probably 40 years.

Most of us who were adults by that time know this much. We still might ask: How? Who? And why wasn't he caught sooner? These questions and others are what Richard Behar's new book, "Madoff: The Final Word," is about.

I will digress here for readers who wonder what a Ponzi is and quote from Mr. Behar directly: "The mechanics are simple, but irresistible to the gullible. A Ponzi's architect uses the allure of fantastical returns to lure in the [initial and] next wave of investors; each subsequent wave's money is used to pay off the previous wave. . . . So long as there is a sufficient supply of new money coming in at the bottom of the pyramid, the schemer can afford to pay other investors — especially those higher up," i.e., the most favored, "the promised returns. If, for whatever reason, the supply of new money dries up, and investors start requesting (or demanding) their money, that's when the plunderer either gets busted or flees," as in 2008.

One more point. There are no real investments, and promised returns are also fake: They are all paid out of new investor money inputs.

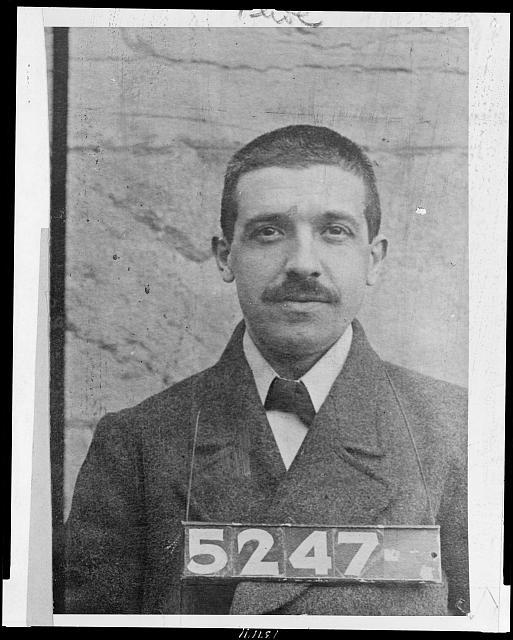

The name for this type of scam comes from a swindler called Charles Ponzi, who in 1920 promised investors a 50-percent return within months. He was exposed that same year by a financial journalist who closely examined his investment claims. Madoff was more fortunate. It seems no one looked closely into his claims for four decades.

New York World-Telegram and The Sun Collection, Library of Congress

The front through which all this was carried out was Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities (henceforth BLMIS), including a trading operation run by Bernie's brother and two sons that did not make money or ran at a loss, an international operation based in London and "House 17," on the 17th floor of Manhattan's Lipstick Building, "home of the so-called investment advisory unit . . . where the Ponzi grew and thrived and spread throughout the world like a pandemic — and where most of the firm's money, it turns out, was earned and kept."

The initial investors and players were members of the extended Madoff family and their neighbors in Queens, as described in Chapter 2. "The closest and oldest pals — the insiders' club — were making 30 percent, 40 percent, even 50 percent returns." So at those rates, say 40 percent, a million dollar investment would grow to $2,744,000 in three years if their "returns" were reinvested each year, or the insider would have a cash income of $400,000 each year. Remember, the original million was never invested in anything, the incremental $1,744,000 was fictitious, and the cash payment came from the next sucker's opening cash investment. Eventually, this process built up to $68 billion of fake money.

What rational person would believe promises of such returns — certain and continuous on financial investments that are notoriously volatile in the real world? Investors got printed statements in the mail, counterfeit forms reporting fake trades taken by BLMIS from issues of The Wall Street Journal. A close look by anyone with investment experience would have revealed the fraud.

But it seems no one looked. Why? Greed.

That's an important message of this book: It takes two to tango. Bernie could count on his clients' greed to keep the ball rolling.

I had spent 10 years on Wall Street, and I personally remember a friend announcing to me that he had been invited to invest with Bernie at a guaranteed rate of 15-percent return. I said, "That is impossible." His reply was (sniff), "You must not know what you are talking about."

BLMIS also grew exponentially through the complicity of feeders in both the U.S. and Europe. The "largest feeder fund conduit was the Fairfield Greenwich Group . . . which had . . . some $7 billion of customer funds invested with [Bernie] at the time the Ponzi collapsed." Cohmad brokerage "was a massive feeder into the Ponzi." Another was Sonja Kohn, an Austrian banker, and R. Thierry Magon de la Villehuchet, manager of a multibillion-dollar Madoff feeder fund who escaped prosecution in 2008 by "cutting his wrists and biceps, and bleeding out into a wastebasket in his twenty-second-floor Madison Avenue office. Security officers discovered his body in a chair, with one leg propped up on his desk."

Another organization with questionable involvement in the scam was — amazingly — JPMorgan Chase, the largest bank in the U.S. All of BLMIS's cash transactions, in and out, went through just one account at the bank, known as number 703. "For instance, between 1986 and 2008, Bernie's 703 checking account received deposits of about $150 billion . . . more than 7 percent of JPMorgan's total global assets in 2008. . . . These circular, redolent transactions, each for tens of millions of dollars, took place on an almost daily basis for years. . . . Anyone looking closely at the monthly account statements would have seen zero securities purchased with it."

In other words, not a trivial account to go unnoticed. While Chase's behavior may not have risen to the level of a criminal conviction, it was very, very bad. "Extremely negligent" would be the kindest phrase one could apply. In 2014, JPMorgan Chase, "in order to avoid pleading guilty to a criminal indictment, admitted to a set of damning facts about its colossal failures, paying $2.6 billion in fines, penalties, and settlements. . . ."

As to who knew, Mr. Behar makes a strong case that Bernie's wife, Ruth, knew, as did both of his sons — Mark (who committed suicide) and Andrew (who died of leukemia). For one thing, Ruth's father, Saul Alpern, an accountant, was in on the ground floor. "In the early 1960s Saul formed his own group of investors, consisting mainly of his accounting clients, to provide money to Madoff." However, in the end, only five BLMIS employees were convicted of fraud, including Bernie's brother, Peter. Plus, of course, Bernie.

What brought down this house of cards? In 2008, Bernie could not pay out the promised returns of $250,000 to a European bank. There was not enough new money coming in, so Bernie "confessed" to his family so that the sons would look clean by turning him in to the feds. In the end, Bernie was sent to prison for life. He talked to the author from inside.

Many have credited Harry Markopolos, a quantitative analyst in Boston, for alerting the Securities and Exchange Commission. "Based almost entirely on Markopolos's version of events, many have laid the blame for the Madoff affair — or at least its longevity — squarely on the SEC. . . . In his letters to the agency, Markopolos provided no hard evidence. He asked to be paid a bounty." So much, according to Mr. Behar, for Harry's credibility.

"The real reason the much-maligned agency was unable to detect Madoff's fraud" was that $68 billion is 50 times the agency's budget, which is allocated by Congress each year and is inadequate to the responsibilities assigned to it.

Still, the S.E.C. is cast as a leading villain in the case while few of the "victims" blame themselves for their gullibility and greed. Bernie's brain made the poison, he sold the Kool-Aid, but they drank it. And kept on drinking it for years.

Did Bernie ever show remorse for all the people he cheated — in some cases out of their entire life savings? Again, as he said when he was caught: "Now all of a sudden everybody is upset."

I have one complaint about this book. Its lack of an index made it hard to cross-reference and difficult to write about.

Ana Daniel, retired from business and academia, lives in Bridgehampton.

Richard Behar is a contributing editor for Forbes magazine. Bernie Madoff had an oceanfront house in Montauk. He died in prison in 2021 at the age of 82.