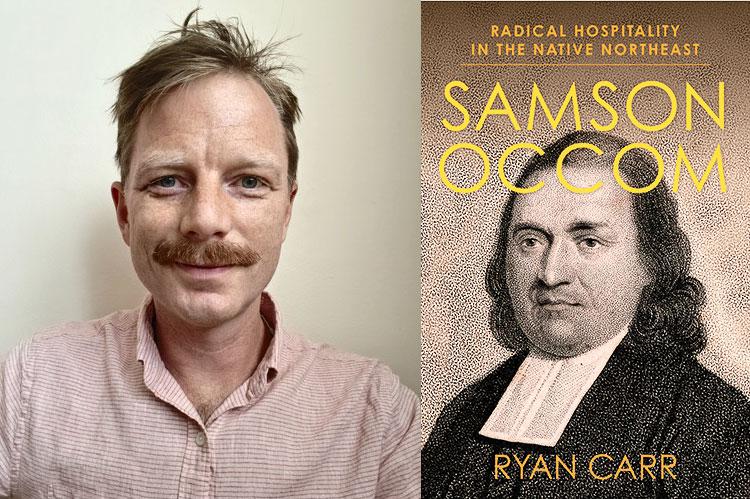

“Samson Occom”

Ryan Carr

Columbia University Press, $35

Lifting the veil off the distant past can clarify aspects of our nation’s history that have been either ignored or misinterpreted. What Ryan Carr has done in his new scholarly book, “Samson Occom: Radical Hospitality in the Native Northeast,” is just that.

Mr. Carr, a professor at Columbia, has set out to clear up the often cloudy transition between native culture, Anglo-American colonists, and religion through the life and writings of the brilliant Samson Occom (1723-1792), a Native American pastor, teacher, inspiring orator, diplomat, missionary, and tribal councilor. His ties to East Hampton, especially Montauk, will make this book particularly interesting to Long Island historians.

Occom was born in Mohegan, now Montville, Conn., in 1723. His tribe was in decline from war and disease. Colonialism had reduced the Mohegans’ land holdings and left them poor. Their relationship with the powerful Euro-Americans had soured into a crossfire of anger and dejection. It was this oppressive environment that likely persuaded the 17-year-old Occom to convert to Christianity.

He taught himself to read and write to better understand the biblical teachings of the Englishmen’s religion. He often relied on English neighbors for help in his self-education. Occom had heard, probably from one of the frequent evangelical preachers who searched villages for converts, of Eleazar Wheelock’s school in Lebanon, Conn. Through his mother’s intervention, Occom set off to visit the Congregational minister and ended up spending four years in Wheelock’s school.

Occom was a voracious reader and an enthusiastic pupil. Though he suffered from failing eyesight, at the age of 24 he could read English, Latin, Greek, and Hebrew. A persuasive speaker and an inspired teacher, he would become a significant scholar and interpreter of Christian philosophy.

Occom’s tuition had been partially paid by a grant from the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts. His education was intended to lead him to the ministry. He was particularly interested in weaving together the traditional customs and spirituality of his people with Christian beliefs. He continued his preparatory studies with the Rev. Benjamin Pomeroy of Hebron, Conn., but Occom’s poor eyesight made entering Yale College, the usual route to ordination, impossible.

Without that prospect, Occom relied on his ability to teach for an income. In 1749 he moved to Montauk, where he founded a school and held religious meetings for the Montauketts and the Shinnecocks of the region. It is said that he was a schoolmaster, scribe, minister, judge, and doctor to his community.

It was at Montauk that he fell in love with Mary Fowler. They married and started a family. Because of his success and personality, the Suffolk County Presbytery ordained Samson Occom on Aug. 30, 1759. East Hampton’s famous pastor the Rev. Samuel Buell preached at the ceremony. Occom was one of the first Native Americans to be ordained.

While at Montauk he made several missionary trips to preach to the Oneidas in western New York. He received a small allowance for these residencies, but being an Indigenous person, he was marginalized by his fellow ministers and always underpaid for his work or not paid at all. In 1764, the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts offered him a small yearly stipend to return to his birthplace of Mohegan and lead the local congregants.

This was a tumultuous time for native people. The aggressive push by colonists to extinguish native land ownership was rife. It was a nasty situation, and Occom’s letter to King George III asking him for support did not help the native people; it only turned important members of the clergy and the colonial Connecticut government against him. Of course, the colonists triumphed.

It was time for a change, and Reverend Wheelock posed a convenient proposition. Inspired by Occom’s approach to schooling the young Montauketts, in 1754 Wheelock started Moor’s Charity School in Lebanon, Conn. Designed to educate Native Americans as missionaries to their people, it needed money.

Wheelock turned to Occom and the Rev. Nathaniel Whitaker as fund-raising ambassadors to travel to England and Scotland with collection plates in hand. They left Boston on Dec. 23, 1765, and Occom proved to be an exemplary orator. Though there was gossip that he was not a true Mohegan, the trip was highly successful. Occom gave more than 300 sermons and once spoke to a gathering of 2,000.

All in all, they were able to gain the respect of the upper crust and return to Boston in 1768 with over $2,500,000 in today’s purchasing power. While the fund-raising tour was still in progress, however, Wheelock decided to give up on the concept of a school for young Native Americans and used the money for a college for Anglo-Americans. This was the birth of Dartmouth College.

There is no question that Occom felt betrayed by Wheelock’s decision after he had been abroad raising money for enlarging Moor’s Charity School, but he also discovered that Wheelock had ignored his promise to help support his wife and family while he was in the British Isles.

Poor and betrayed, Occom returned to Mohegan. With his usual vigor, he continued his itinerant preaching and devoted himself to formulating his ideal of blending Indigenous traditions with Euro-American Christianity, all for the betterment of his people. Yet he realized that there was no place in New England that could shield his flock from negative colonial pressures. For native people there was little left except intolerance, poverty, disease, and crime.

His plan was to lead a migration of New England’s Christian native people to a new home. He looked west for an area with good soil and water. It would be self-governing, combining both Indigenous and colonial laws. All would be brothers together. In 1774 the Oneidas of New York deeded a tract of land, west of Utica, that Occom called Brothertown. Delayed by the American Revolution, it was in 1785 that the Nation of Brothertown became a reality. Occom became its pastor, and Brothertown was his family’s home until his death in 1792.

Ryan Carr’s exhaustively researched book is not really a biography, but rather an examination of Occom’s philosophy as seen through his writings. Besides penning a short autobiography, he wrote sermons, hymns, journals, and letters. Mr. Carr suggests that Occom was our most prolific native author until the end of the 19th century. The author writes that most of Occom’s texts have been overlooked because the preponderance of them are religious in nature. But logically, since Christianity plays such a major role in his career, these overlooked documents reveal the minister’s thought process and perceptions.

Occom saw a similarity between some Indigenous customs and Christian practices, but he was well aware of how the colonists could twist or ignore important principles of standard scriptural behavior when it suited them. Lust for land led to intolerance. Still, he realized that the traditional welcoming of strangers into a Mohegan village was like the Christian teaching of love thy neighbor as thyself. This had been part of native custom for centuries, hence the words in the book’s subtitle: “radical hospitality.”

As for Occom’s writing, Mr. Carr finds that he is a “plain” writer. Occom presents his ideas straight, simply, at times eloquently but not layered. There is little room for misinterpretation. It is forthright.

I found this book intriguing and enlightening. I knew very little about Occom beyond his time in Montauk. The clash of European immigrants with the Indigenous population has rarely been captured so well by one strong voice. And such an intelligent and caring voice. We are smack in the last half of the 18th century, and our guide is not a white male colonist, but rather a native one, trying to save his civilization.

I found this a thrilling chance to see this world through Occom’s lens.

Richard Barons, former director of the East Hampton Historical Society, lives on Cape Cod.