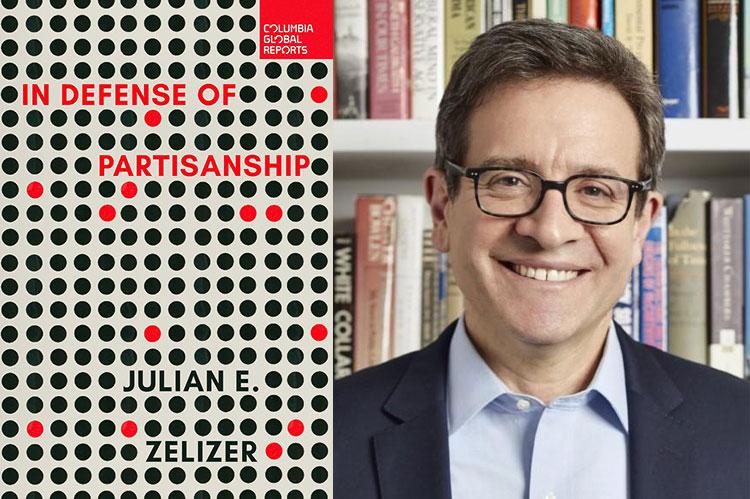

“In Defense of Partisanship”

Julian E. Zelizer

Columbia Global Reports, $18

Of course not.

No way the noted Princeton professor of history and public affairs, prolific author, and TV commentator Julian Zelizer would really sing the praises of partisan chaos in the country today, despite his chosen title: “In Defense of Partisanship.”

Indeed, “Partisanship is a dirty word in American politics,” he begins this short, but timely, scholarly treatise. “If there is one idea on which almost everyone in our divided country seems to agree, it’s that the intense loyalty of Democrats and Republicans to their respective parties is a main source of our democratic ills — division, dysfunction, distrust, and disinformation.”

Rather, Professor Zelizer is looking back at a partisanship that was and ahead to what it might be.

In a truly democratic system, he argues, partisanship requires real parties, coherent in thought and goals, capable of defining and debating problems and priorities, developing broadly acceptable solutions, mobilizing and inspiring partisans in common cause.

But parties today are not what they were — sidestepped and weakened by the dark money of special interests and the prompting of social media. Instead of Democratic loyalists, many see a far looser collection of party factionalists or fractionalists (my terminology), driven by their own particular, not always congruent interests: abortion, health care, gender assignment and reassignment, the poor and marginalized, Israel, the Palestinians, Russian threats, embattled Ukraine, prices at the gas pump and grocery.

On the other side, traditional Republican loyalists have been overtaken by Trumpian Royalists — whether or not actually enchanted by the president’s monarchical proclamations (“Long live the King!”) and declared decimations (U.S.A.I.D., N.I.H./C.D.C., D.O.E., I.R.S. as tax-time approaches, maybe even NATO), to the degree courts permit.

But in either case we find Republicans willing, if not always eager, to shift their views as the president changes course. See Kentucky Senator Mitch McConnell before and after relinquishing his majority leader’s post, forswearing another re-election bid — and casting the lone G.O.P. vote against R.F.K. Jr. for secretary of Health and Human Services.

Mr. Zelizer traces the rise and at least temporary fall of political party power, especially as evident in the not always very merry-go-round of congressional reforms. Ostensibly meant to limit legislative logjams, they continually balanced and rebalanced the respective might of the president, House and Senate leaders, committee chairs, and the long-accepted seniority system that moved elders ever upward, too often able to sideline or snuff out legislation that otherwise might win majority support and make the political system more productive.

In the end, the good professor posits yet more reforms to foster what he calls “responsible partisanship” — more open to truly representative thinking from all sides and all ages about major challenges of our time, with more accountability for what does and does not become law.

“A new era of party-oriented reforms has the potential both to respect the deep differences that divide us and simultaneously to create a more functional arena in which two major parties compete to shape policy while still being able to govern,” Mr. Zelizer wishfully asserts.

Starting at the very beginning, however, he reminds us that the founding fathers dreaded factionalism, “which they perceived to be distinct interests that chased after their own specific objectives as opposed to the common good.” George Washington himself decried the “spirit of party generally [as the] worst enemy of democracy,” tending to “distract the public councils . . . enfeeble the public administration . . . [and agitate] the community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms.” Sound familiar?

But “Ideals were one thing. Reality was another,” Mr. Zelizer concedes, and quotes Senator Martin Van Buren, a creator of the New York Democratic “machine,” for the “organizational potential” he envisioned — and which a notable French visitor, Alexis de Tocqueville, observed circa 1835-1840. “In America the two parties agreed on the most essential points,” de Tocqueville wrote. “Neither of the two had, to succeed, to destroy an ancient order or to overthrow the whole of a social structure.”

Still, the two-party system was not able to bridge a North-South divide that produced the Civil War, nor prevent physical violence that became “a regular occurrence on the floors of Congress,” Mr. Zelizer reminds us.

The reforms of Reconstruction and mandates of the 14th Amendment were steadily neutralized in practice by the South’s often-deadly backlash, Jim Crow. In the North, as Van Buren expected, the party system’s powerful urban machines manipulated political patronage, the power of local taxation, and government operation to generate or enforce loyalty come election time.

There was also a social factor. By the late 1800s, we learn, parties came with real partying, especially at election time.

“In a period when voting rates reached upward of 80 percent in presidential elections,” Mr. Zelizer recounts (no pun intended), “huge crowds gathered to participate in raucous party parades, barbecues, rallies, and other public events. Voters engaged in partisan hoopla with the same verve that twentieth century Americans would revel in sporting events and music concerts.”

Some states required voters to come forward and announce their candidate of choice — or deposit an easily identified “ticket” for him (only males in those days) into a large, transparent glass bowl. All of which could subject those exercising the franchise to pressure or punishment from party leaders and powerful moneyed interests.

But by 1891, secret voting (first known as the Australian ballot) had become a hallmark of American democracy, cutting election violence, intimidation, bribery, and party power — helping pave a path to the Progressive Era.

Enter a young Princeton and Johns Hopkins grad, Woodrow Wilson, later the nation’s 28th president (1913-21), first teaching at females-only Bryn Mawr College, though privately no fan of higher education or political roles for women — or Black men (see “Women, Race, and Wilson Revisited,” East Hampton Star, Jan. 2.)

His graduate treatise, published in 1885 as “Congressional Government,” swiftly spread his notion that the committee system in Congress had so overly segmented power that decision-making was too often elusive, and with too many constitutional checks and balances that could block necessary presidential proposals on complex issues in troubled times. “We are ruled by a score of ‘little legislatures,’ ” Wilson complained.

And so began the continuing cycle of reform, regulation, deregulation, and other executive and legislative approaches to — or avoidance of — the ever-expanding array of American problems and divergent views. The New Deal. The Great Society. The Reagan Revolution (“Government is the problem”), which still drives today’s downsize-and-abolish frenzy to Make America Great Again.

What does Mr. Zelizer suggest? “Responsible partisanship” might be encouraged if Senate filibusters were more difficult to mount and thus more rare. Tighter limits on campaign donations and independent spending would reduce outside influence by the wealthiest individuals, corporations, and interest groups.

Some form of public financing, perhaps at least matching grants for small or medium contributions, also would reduce the endless time those elected still must spend on fund-raising to keep their seats. Annual debt-ceiling debates (and threats of government shutdown) could be replaced by a system of automatic increases based on the level of spending and taxation to which Congress and the president already have agreed.

Mr. Zelizer also envisions the House of Representatives itself enlarged from the 435 seats of Wilson’s time, locked in by the Permanent Apportionment Act of 1929, when the population was half its current size. More members from smaller congressional districts would bring all voters a closer connection — and more influence — with the political process, as would more in-person and online outreach, round tables, and town hall meetings.

But in the end, “procedural and organizational reforms won’t be sufficient,” Mr. Zelizer admits. “If we have learned anything in recent years, it is that leadership matters a great deal in shaping the direction of politics, more so than many earlier generations of reformers realized.”

“Congress needs elected officials who embrace partisanship but demonstrate that the quest for power must not overwhelm all other obligations,” he concludes. “The time has come for bold thinking in American politics. . . . If we don’t alter course in the near future, we will keep dividing ourselves to death.”

The party turned wake.

Julian E. Zelizer has a house in Sag Harbor.

David M. Alpern, also a Sag Harbor resident, was a reporter, writer, and senior editor at Newsweek magazine, for 30 years hosted the “Newsweek on Air” network radio show, later the independent and nonprofit “For Your Ears Only,” and now interviews authors for local libraries.