HE WORKS OBSESSIVELY every night, often till the sun comes over his compound: the farthest-out home on Long Island’s South Fork. Hours later, after a restless sleep, Peter Beard walks out to the edge of the bluff, sits on a boulder, and watches the birds wheel and keen over the sea. “I always feel better,” he says, “when I’ve done a bit of this.”

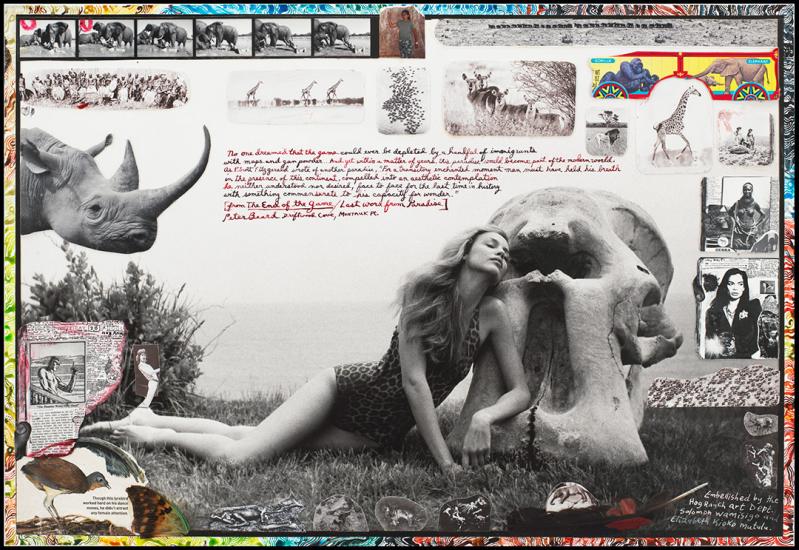

At 78, Beard isn’t letting up after a half-century of gorgeous, idiosyncratic art chronicling his two lives in Kenya and Montauk. Photographer, painter, and writer, he still mixes his media like a witch doctor, conjuring the bold, mesmerizing journals that have made his name. Portraits of proudly naked tribal women dominate the African ones, collaged with feathers and dried leaves, and even his own blood, old sepia-toned images or newspaper clippings, hand-written prophecies about the natural world.

The Montauk journals feature pictures taken long ago of famous friends who came to stay, from Jackie Onassis to Truman Capote.

Now, in his first solo show in l5 years, Beard has put 50 of his artworks from both worlds on the walls of East Hampton’s Guild Hall, from journal pages to huge mixed-media portraits. It’s a hell of a show, from one of the South Fork’s most enduring — and dashing — artists.

With British movie-star looks and a liberating trail of old money (tobacco on his father’s side, railroads on his mother’s), Beard first went to Kenya in l955. Inspired, he bought land adjacent to Karen Blixen’s famous coffee plantation. There, he bore witness to the start of the end for big game, as Africa’s human population exploded and animal habitat declined. A grim Cassandra, he scoffed at conservationists fighting to save as many elephants as possible: That would only destroy them all. Better to cull the herd and draw up a seat for the inevitable apocalypse.

That dark view suffused "The End of the Game," his 1956 classic on the decline of the natural world.

Montauk began for Beard as weekends with Lee Radziwill, his inamorata of the early 1970s. The couple stayed on an old oceanfront property bought by Paul Morrissey, Warhol’s filmmaker, for $225,000 in 1972; earlier this year it sold for about $50 million to Adam Lindemann, an art collector.

“Lee and I had this dream,” Beard explains. “She had these aunts, the Beales, who were being bullied by the Town of East Hampton. We were able to get through that door, and found an absolutely fabulous, eccentric couple, and we made them our project.”

With Jackie Onassis’s help, Beard said, he and Radziwill lined up the documentarian Albert Maysles to tell the Beales’ story. It became the fabled movie Grey Gardens.

Beard bought his own six-acre estate on the bluffs at Montauk, nabbing it just in time from Arthur Miller and Marilyn Monroe. To its several cottages, he added a windmill moved from Ditch Plain.

“Instead of the African plains,” Beard says of Montauk, “it had the vastness of the ocean.”

Both were primitive landscapes, both imperiled.

The Rolling Stones came out to visit, and recorded Exile on Main Street in the mill and cottages. “Unfortunately there was a radar tower that emitted this horrible series of noises every 45 seconds,” Beard recalls. “They would hear it on their earphones — it was extremely annoying.”

Halston stayed at the mill, too, designing canvas furniture coverings to pay for his stay. Tragically, in 1977, the mill burned down, taking with it all of Beard’s early journals — he’d started at the age of 8 — and artworks, though fortunately not including any of the portraits of him by another new friend, the artist Francis Bacon.

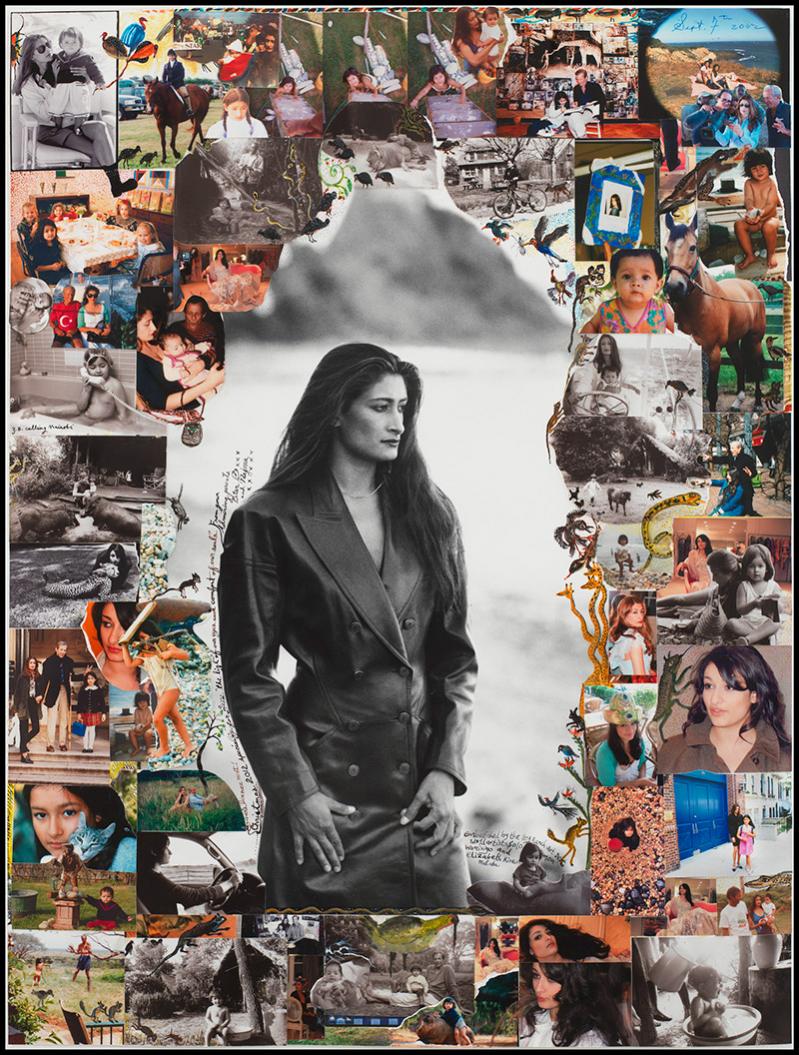

Beard was a ladies’ man of the first order who’d sailed through Studio 54 with a succession of beauties, including Cheryl Tiegs, the supermodel he married in l982. But by the end of l986, he was ready for monogamy. He married Nejma Khanum, 20 years his junior, and the two had a daughter, Zara, who, at 27, is now his full-time studio assistant.

The main house where Beard works is itself a creation crammed with paintings, knives and spears from Kenya, rugs and baskets, first-edition books on Africa, and more. Beard’s health is not quite what it was: Where once he spoke in a torrent of words, riffing for hours on the natural world’s demise, he speaks more slowly now. Still, ask him how Montauk has changed, and he starts to rail at the architecture, the crowds, the loss of a wind-swept, frontier culture where fellow pioneers like the songwriter Paul Simon, the photographer Richard Avedon, and the TV talk show host Dick Cavett might come for dinner.

Beard isn’t quite the lonely bluff dweller he sometimes seems to be. He and Nejma have a rambling apartment in one of the great buildings on the West Side of Manhattan, filled, like the Montauk house, with marvelous treasures. Window ledges are lined with African artifacts, walls covered with large framed paintings. Low against one wall is a framed letter from Livingston to Stanley; high on another wall is a large oil portrait of Nejma by Julian Schnabel.

A Bacon sketch of Beard would be here, too, if it were not on loan to the Tate. It’s all testament to Beard’s searing curiosity, his passion, and ultimately his despair at the state of the world.

“When I first met Peter he would be ranting about every-thing,” Nejma says. “I would say, ‘Please stop, it’s so depressing!’ People thought he was bonkers.”

Over the years, she’s come to share his views — after all, his predictions have come true. “I do care very much what he’s been doing,” she says now, “and I share those ideas.”

The journals, all those decades’ worth, aren’t a personal narrative. “But there is a narrative,” Nejma explains, “If you under-stand about what man has done to this world.”

Nejma is, like Beard, wary of Montauk’s build-up. But there’s land enough to keep the world at bay.

“Where we are it still feels like ancient land,” she says. “You feel like the ancient people are still there, and that there is some-thing so sacred there, such solitude and peace. We do see the houses next to us getting bigger, but as long as we have our property, we feel safe.”

By the time this story appears, the Guild Hall show will have opened (It lasts from June 18 until July 31). Its title: Last Word From Paradise.

Fifty years after The End of the Game, Beard is still seeing through a glass darkly.

But seeing the walls filled with his art may cheer him up yet. “I think he’ll be very happy when he sees the show up,” Nejma says. “We want to make it a celebration of P.B. He’s had a wild life, and we’re lucky he’s around.”

Last Word From Paradise is a museum show with no works for sale; to make inquiries about saleable work, Peter Beard’s studio can be contacted at [email protected].