On March 22, 1984, the Wind Blown, a commercial fishing boat, departed from Montauk Harbor on eastern Long Island around dusk to begin its first trip of the early-spring season. The four-man crew planned a weeklong trip to catch tilefish about 120 miles offshore.

It was a gray, frigid, 40-degree afternoon. A light easterly wind indicated the possibility of a brewing storm, but it was nothing that Capt. Michael Stedman thought his 65-foot, steel-hulled boat couldn't handle.

Back then, even vaguely reliable long-term weather forecasting didn't exist. Offshore fishermen received twice-daily weather updates on single-side-band radios. And if you weren't standing in your wheelhouse at five o'clock in the morning and eleven o'clock at night, your radio tuned to channel 2670, you missed it. For commercial fishermen, as Mike knew firsthand, a little weather was nothing to fear — an occupational hazard if ever there was one. Besides, if things got really bad, he could always run back to the harbor and ride out the storm.

It was Mike's fourth or fifth offshore trip aboard the Wind Blown, and the young, relatively inexperienced crew hadn't yet jelled. The foursome was still figuring out how best to work together. Mike had purchased the Wind Blown only months prior, after years spent working on other men's boats. At long last, he was the captain of his own vessel and in control of his own destiny — financial and otherwise. Captain Mike answered to no one but himself.

The year 1984 was the height of the commercial tilefishing boom — right in the sweet spot of a decade-long East Coast fishing gold rush that spanned from the late 1970s to the late 1980s. Historic numbers of golden tilefish flooded the North Atlantic. It was pretty much a guaranteed bonanza for anyone who geared up, went out, and did it. Back in those days, baited circle hooks pulled in 30-to-40-pound tilefish. It was like plucking money from the sea: soaking-wet dollar bills that reeked of rotten fish guts.

Depending on the going price and grade of tilefish, a successful offshore trip promised a longlining crew anywhere from $15,000 to $30,000. Once they pulled back into the docks, the crew filled cardboard cartons like bakers frosting a layer cake: ice, tilefish, ice, tilefish.

Whatever landed in Montauk traveled the length of fish-shaped Long Island by truck to the Fulton Fish Market in Lower Manhattan, where it was sold through brokers, mostly to Chinese and Korean buyers. What the commercial fisherman gained in freedom, he lost in transparency, since the pricing structure, like the catch, fluctuated according to supply and quality and freshness — to say nothing of the weather and proximity to holidays and school vacations. Though the Fulton Fish Market has since moved to the Bronx, nearly all of Long Island's annual catch still ends up there. Haggling was the name of the game; the difference of 30 cents a pound could make or break a 20,000-pound haul. Decades prior, the Mafia had taken control of the Fulton Fish Market, seeing it as an ideal, all-cash business for laundering money.

The truck driver eventually returned to Montauk carrying thick wads of cash. Receipts in hand, each boat owner first subtracted the cost of the trip. In 1984, a typical week offshore ran about $5,000 for food, fuel, and ice. No one got paid until the crew had hosed their vessel clean of blood, dirt, and rusted fishhooks. Cash was king. Some years, owners pulled in upwards of a quarter of a million dollars.

Then as now, commercial fishermen weren't salaried employees. Deckhands worked for a share of the catch — less the owner's and captain's slices of the pie (typically an equal split). Any fish that wasn't the target species (in this case, golden tilefish) went into a separate cardboard box the crew labeled shack money. The deckhands kept the profits from whatever they caught that wasn't the target species. (A 75-pound swordfish, at $5 a pound, netted a sizable chunk of change.)

Two of the four men on the Wind Blown — Michael Stedman and David Connick — were an improbable pair to have joined forces on an offshore commercial fishing boat. Most Montauk fishermen come from working-class families. Few attend private schools. Blue-blooded pedigrees are rarer still.

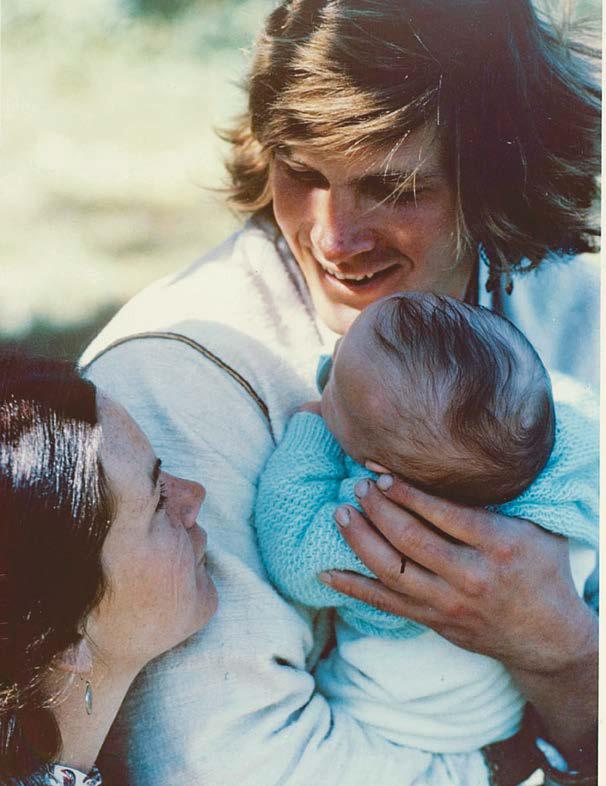

Mike was the 32-year-old son of a Harvard-educated United Nations civil servant. Dave, his 22-year-old mate, was the son of an affluent New York family who belonged to the Maidstone Club and owned a weekend house south of the highway in East Hampton.

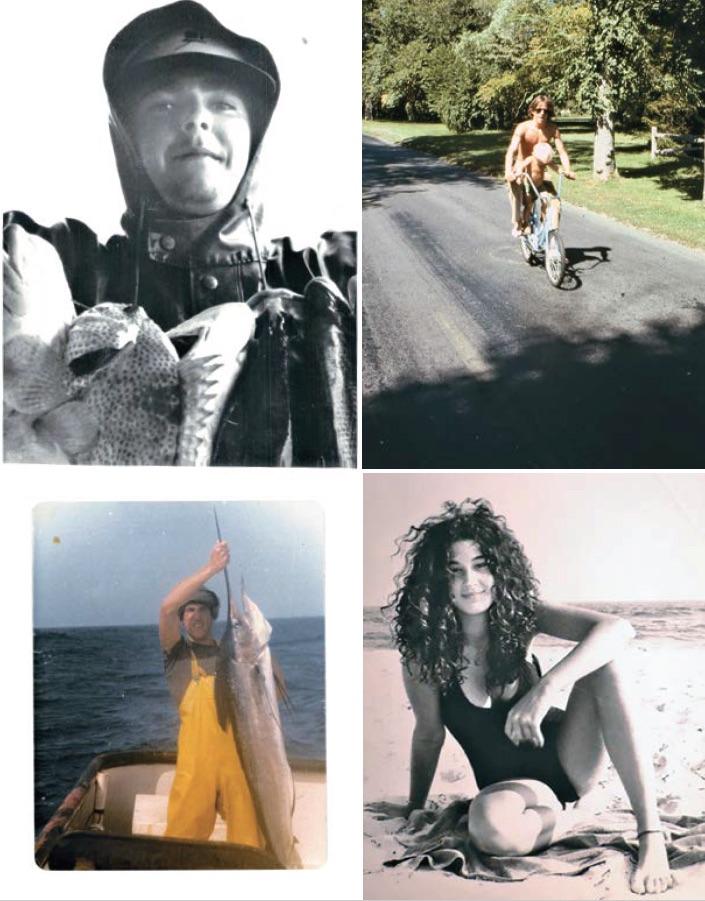

Though separated by nearly a decade, Mike and Dave were like brothers, the privileged sons of powerful, domineering fathers. It was a different era, and their fathers had a lot in common. Both were white-collar men who liked to drink and had wandering eyes. For Mike and Dave, nothing was less appealing than the dry-cleaned suits and suspenders their fathers wore to the office every morning. Social climbing and cocktail-party banter made their skin crawl. The decision to become commercial fishermen was an act of defiance, a discarding of their inheritance. Mike and Dave showed their rebellion by growing chin-length hair, streaked by the sun. Unlike their fathers, their athletic, sinewy bodies were the result not of playing regular games of tennis or golf but years of riding waves.

Most Montauk fishermen don't surf. Some don't even know how to swim. In that regard, Mike and Dave were outliers too. If they weren't offshore fishing and the surf was breaking, they could be found at Georgica Beach in East Hampton or Ditch Plain in Montauk — out in the water, straddling their surfboards, their torsos facing the horizon, waiting for another set to roll in — part of a small, insular tribe of eastern Long Island surfers.

The two other men on the Wind Blown's final voyage, Michael Vigilant and Scott Clarke, were young, enthusiastic deckhands from scrappy, hardscrabble families. They were busy sharpening their skills and putting in their time, eager to someday become captains of their own vessels.

Michael Vigilant, the 19-year-old son of a commercial fisherman, was a familiar face around the docks but new to the Wind Blown crew. He was filling in until Tom McGivern, one of the original Wind Blown crewmembers, returned from a surfing trip to the Canary Islands. At 18, Scott Clarke was the fourth and youngest crewmember. A relative newcomer to Montauk, Scott was already well on his way to cementing his reputation as a young man with an ironclad work ethic who wasn't afraid to get his hands dirty.

As lowly deckhands, Michael and Scott were enticed by the cash they might make. Every offshore trip was a bit like gambling, albeit with the advantage of a stacked deck. Each crewmember stood to make between $2,500 and $5,000 for a week of work. With three to four trips each month, the money added up. Even so, the three youngest members of the Wind Blown crew (lacking mortgages and young mouths to feed) could easily drink through it in a week's time. Already the father of three sons, Captain Mike didn't have the luxury of pissing away a week's worth of wages. He occupied a separate tier of the hierarchy altogether. As owner and boss, his rank entitled him to an additional percentage of whatever he and his crew hauled back to shore.

But the pull wasn't only about the money. It was about the spirit of the thing. Hundreds of miles offshore, different rules applied. Aboard the Wind Blown, no matter the foursome's divergent social classes, a brotherhood had started to form. And not by accident, but on purpose: Their very lives depended on it.

Commercial fishing has always been a young man's game. Few fishermen work past the age of 50. For some, the older they get, the more the close calls accumulate. And the baton eventually gets passed from one generation to the next. Every offshore trip is an endurance test. Each crew works to the brink of exhaustion — and often well past that. Commercial fishing is all about pushing boundaries. It becomes a point of pride, the ability to ignore all indications that your body needs to stop and sleep.

Offshore, the mentality is to fish until you simply cannot fish any longer. With a fatality rate 20 to 30 times higher than that of other occupations, commercial fishing is among the most dangerous jobs in the nation. Sinking vessels cause the greatest number of fatalities, followed by fishermen falling overboard. After tabulating annual fatal workplace injuries, the Bureau of Labor Statistics consistently ranks commercial fishermen above timber cutters (second) and airline pilots (third). For purposes of survival, fishermen (and deckhands especially) develop a remarkable sense of timing and balance. But the danger of the work rarely registers for young men, whose whole lives are stretched out ahead of them, like so many miles of monofilament fishing line.

"A fisherman is like a good cheese," Hilda Stern, the wife of Richard Stern, a legendary character among the Montauk fleet, said in a profile about captains' wives that appeared in 1976 in The East Hampton Star, the local newspaper. "He just goes on forever."

Mike Stedman was one such fisherman who was sure to get better with age. Longevity coursed through his bloodline. A confident man in the prime of his life, Mike had a smile that radiated contentment. As captain, he relished the healing solitude of being out on the water, the quiet hours alone in his wheelhouse to sit and think, with only the natural world to keep him company, and nobody to bother him. Mike probably never said as much out loud, but he was driven to prove something. It was time to make something of himself.

Deep in the recesses of his mind, though, it's possible that Mike had started to second-guess himself. The rumors swirled around the docks. Originally a Long Island party boat with a plywood pilothouse and four fish boxes cemented to its deck, the Wind Blown wasn't built for the fierceness of the North Atlantic. The 15 feet added onto her stern by a previous owner had created a destabilizing weakness. Cruder still: Several members of the fleet said she was an unseaworthy piece of shit.

"I remember when Mike brought that boat into the harbor, and seeing that it was a steel hull with a plywood structure," Rick Etzel, a Montauk commercial fisherman who now owns the Breakaway, told me. He remembered thinking: Man, that's not a good combination. For Rick, the addition of the longline drum, which Mike and a friend had bolted onto the roof of the Wind Blown's wooden pilothouse, was but "another head-scratcher."

At the time, the Wind Blown was all that Mike could afford. She was a starter boat, a common first purchase among members of the Montauk fleet. Back then, many starter boats were made of wood. In fact, given the Wind Blown's steel-hulled underside, Mike was doing better than many of his peers. But with a mortgage, three children, and a $7,000 insurance payment due in a week's time, any repairs or modifications to Mike's brand-new acquisition would have to wait until he owned more of the Wind Blown than the bank did.

Mike was easy to love. He was the cool guy. Everyone wanted to be around him, whether as his friend, as a fisherman, or as a surfer. But his steely will was as strong as his body, and people innately sensed that it was better not to cross him.

Early Wednesday, the day before their March 22 departure, the crew began cleaning and refueling the boat at Montauk Harbor, just off West Lake Drive. Dave and one of the younger men went "grub shopping" at the North Main Street I.G.A. in East Hampton. They filled three or four shopping carts with $800 worth of calorie-dense groceries — enough food to fuel four men working 18-to-20-hour shifts for the next five to seven days.

Six dozen eggs. Loaves of wheat bread. Gallons of orange juice. Packages of English muffins. Containers of oatmeal. Boxes of spaghetti. Jars of Rag£ tomato sauce. Strong coffee. Everything except for three things: fish, bananas, and alcohol. Fish you can always catch. Bananas are bad luck on fishing boats, a long-held superstition dating back to the slave trade when banana boats were struck by tropical hurricanes — and sank. (Another story goes that a boat carrying a shipload of bacteria-laden bananas killed everyone aboard.) As for alcohol? Once offshore, even beer is technically forbidden.

Most offshore fishermen, the Wind Blown foursome included, more than made up for weeklong periods of forced sobriety back on dry land. The air would smell sweetly of freshly rolled joints. Miller High Life, "the champagne of beers," flowed like water. Silver cans of Pabst Blue Ribbon did too.

On Thursday afternoon, Mike kissed and hugged his wife, Mary, and their sons goodbye. His departure that day was nothing out of the ordinary. There was nothing romantic about it. Mike was the provider. It was time to get back out on the water so he could feed his family.

For the three months she called Montauk home, the Wind Blown docked in a slip behind what was then Christman's Restaurant and Bar. Once Mike made his way to the boat, he brought onboard the broccoli and tuna-fish casserole Mary had topped with bread crumbs and freshly grated cheddar cheese.

By afternoon, Dave and Scott were already on the Wind Blown, readying supplies, loading ice, and tossing pieces of squid and mackerel into a plastic bucket to use as bait. Once offshore, they'd supplant it with any eel or trash fish they caught. Mike stood watch from inside his wooden wheelhouse, double-checking gear and stowing away an extra full-body survival suit a fisherman friend had loaned him, just in case.

Fueled up and ready to go, the Wind Blown was prepared for just about anything that came her way. She had a VHF radio, a single-side-band radio, radar of at least 25 miles, a Loran-C (a hyperbolic radio navigation system), paper charts, and a magnetic compass. A United States Coast Guard inspection from Star Island, Montauk, on February 23, 1984, had confirmed the "presence of proper lifesaving equipment" on the boat. In 1984, most Atlantic fishermen, Captain Mike included, had yet to invest in weather-fax machines, which, at the time, measured a little larger than briefcases.

Michael Vigilant was the last to board the Wind Blown that Thursday afternoon. He wore black rubber boots, jeans, a blue flannel button-down shirt, and a denim jacket. Although no one knew it at the time, he had just proposed to his girlfriend.

Young and in love, Michael and Kim Bowman, an 18-year-old senior at East Hampton High School, kissed passionately on the docks that afternoon, their bodies pressed tightly together. Moments earlier, hoping to repair a recent argument, Michael had impulsively offered his hand in marriage. Kim didn't give Michael an answer to his proposal. She promised him they'd talk more about getting married in a week's time, when he got back.

Finally Michael disentangled himself. Kim and her younger brother, Frankie, waved goodbye from the docks. They watched as the Wind Blown steamed down the narrow, rocky inlet, past Gosman's Restaurant. The boat turned right, out toward the Montauk Lighthouse, and headed southeast into the vast Atlantic. Minutes later, the Wind Blown reached the edge of the violet-streaked horizon, and quickly motored out of sight.

On Friday, March 23, the sun was not yet an hour high when the men, dressed in foul-weather gear (typically chest-high rubber waders held up with suspenders), went about the tricky task of setting their lines amid the rolling, churning seas. Fish usually bite best at first light, dusk, and high tide. When fishing with a drum, the hooks are typically set over the stern and hauled in at either port or starboard. (When facing toward the bow, or front, of a boat, port and starboard refer to the left and right sides, respectively.) The Wind Blown crew was longlining for tilefish at the edge of the continental shelf, near Veatch and Atlantis Canyons. Down below, hundreds of fathoms beneath the inky-blue, rumpled surface, vast underwater mountain ranges were fertile with marine life.

The crew set out dozens of miles of galvanized steel cable, which fed out from the longline drum fixed to the roof of the Wind Blown's plywood deckhouse. About 30 feet separated each pre-baited circle hook. After the snap-on gear had soaked in the water for a few hours, or overnight, it was time to test it out — and if the fish were biting, to start pulling it back in. The first mate worked the rail, hauling in the yellow-speckled tilefish, alive and squirming, from the ocean floor. The second mate removed the hooks and then, knife in hand, slit the throat of each fish; when they had bled out enough, the third mate would gut them and pack them on ice. It was teamwork, and the Wind Blown's foursome would not yet have been wedded to their particular roles in the way that some more seasoned crews are; the men willingly alternated roles until they found their groove, until they found the rhythm of the sea. If the fish were biting, the crew easily cycled through thousands of baited hooks each day.

Longlines can be set near the surface to catch swordfish or tuna — or near the bottom to catch monkfish or tilefish. The Wind Blown crew, hunting golden tilefish, sank the heavy lines near the ocean floor, marked off by aluminum poles with radar reflectors, strobe lights, and flame-orange, inflatable high-flyers (a type of buoy) at either end. With thousands of dollars of gear soaking in the water, the foursome shared a meal Dave had prepared in the galley using a propane stove.

The men needed food that stuck to their ribs. Dave might fry up a steak with baked potatoes. Other nights, dinner looked like grab-and-go sandwiches, piled high with deli meat and generous dollops of mayonnaise, or plate-size squares of Mary's tuna-fish casserole. After dinner, they'd take turns getting a few hours' sleep, interspersed with two-hour shifts in the wheelhouse. The men learned to tell time based on the phases of the moon and the height of the sun at noon. On clear nights, constellations illuminated the night sky. Once dawn came, the smell of freshly brewed coffee stood in for alarm clocks.

Day after day, the pattern repeated itself. Though monotonous, a repetitive, predictable routine was what the men needed to transform steel fishing lines into a paycheck substantial enough to be split four ways.

The Wind Blown's first few days offshore on this March trip weren't especially fruitful. Fish aren't dispersed in equal numbers throughout the ocean. The act of catching them is both an art and a science, requiring that fishermen be acutely attuned to the present moment. A quarter-degree change in water temperature can shift their migratory patterns — as can shifting tides, wind, the time of day, and a whole host of unpredictable factors. It's often a game of luck and instinct, predicting where exactly they'll congregate next. All that week, the crew persevered. Captain Mike eventually hit the jackpot. He transformed the Wind Blown into a fish-catching machine. His crew started hauling in thousands of pounds. Tilefish were coming up on every hook. Fishermen describe such conditions as "boiling hot."

As the week wore on, the weather worsened. Late March in the North Atlantic is unpredictable and often brutal. Storms can well up overnight. The wind rarely stops blowing. The air is bone-cracking cold, the kind of chill you can't shake, no matter how many cups of coffee you've drunk. Though technically springtime, late March on the East End of Long Island can feel as bitter and raw as January.

On Wednesday, March 28, at 2 o'clock in the afternoon, the National Weather Service in New York City posted a gale warning. Back in Montauk, Chuck Weimer was out day-fishing for flounder on his 40-two-foot boat, the Zeda, in Block Island Sound. He noted in his red leather logbook: "Really pretty rough in the late afternoon," and observed that winds were blowing easterly at 20 to 30 miles per hour. "All boats on their way in."

Later that evening, the National Weather Service upped the ante, issuing a winter storm warning. But the forecasters gravely missed the mark. As the mass headed north, it formed an eye, around which the wind flowed east to west, with the northwest quadrant headed straight for eastern Long Island. Winds picked up from 30 to 50 to 75 miles per hour. The Montauk Point Lighthouse eventually reported wind gusts of over 100 miles per hour.

Any Montauk-based fishing vessels that were still out had started making their way back toward land. Each captain adopted a different strategy for navigating the pitch-black, angry seas. Some docked to the north in Stonington, Connecticut, for the night. There are worse ways to spend a stormy, early-spring evening than saddled up to a bar, a few drinks in.

Kevin Maguire had been out fishing for yellowtail flounder aboard his boat, the Pontos, a 55-foot steel-hulled vessel with a plywood wheelhouse, before taking shelter in Stonington. That night, when he and a group of his buddies walked toward the Portuguese Holy Ghost Society, a popular watering hole among Connecticut fishermen, the wind was blowing at 80 to 90 miles per hour and kept pushing him backward. Kevin felt weightless. "It was like you were flying," he recalled. With his arms outstretched, only the tips of his toes clung to the pavement. All these years and hurricanes later, try as he might, Kevin has never been able to replicate that feeling of weightlessness.

Richie Rade, the captain of the Marlin IV, had been out in Atlantis Canyon, near the Wind Blown, longlining for tilefish. Atlantis Canyon is about 120 miles southeast of Montauk Point. Richie and Mike made radio contact around nightfall. High winds made the rain blow sideways. Richie's men couldn't see a thing. Mike informed Richie that he was heading back. Richie took the long way home. Rather than risk the treacherous sliver of ocean that divides Montauk Point and Block Island, he headed north around Block Island. With the inlet into Montauk Harbor impassable because the water was so high, a dozen other vessels dropped anchor in Fort Pond Bay a few miles west of the Montauk Point Lighthouse.

Low and slow was the name of the game. In theory, if a vessel stays low in the water, crashing waves break over rather than overturn it. No captains I interviewed panicked enough to dump their catch. One vessel, caught in a rip current, sent out a Mayday alert; the Coast Guard (the nearest headquarters were in New Haven, Connecticut) sped to its rescue. Sensing danger, some captains headed in the exact opposite direction — farther offshore. It's the counterintuitive notion some seamen believe carries the greatest likelihood of survival: pointing the bow of a boat toward oncoming waves is a safer bet than if the vessel's stern (or rear) is the first point of contact.

With thousands of pounds of sweet, buttery tilefish stored inside wooden boxes packed on ice, the Wind Blown careened up the East Coast; the eastern tip of Long Island was square in her path. The Wind Blown soon confronted not just a storm, but a dreaded nor'easter. The National Weather Service later described it as "one of the most severe general cyclonic storms in recent history."

From the Carolinas to New England, warm, moist air from the Atlantic collided with cold air descending from Canada to create a degree of atmospheric instability and intensity few, if any, weather forecasters had predicted. Thirty-six thousand Long Island residents lost power that evening, as surging tides flooded basements and hurricane-force winds downed trees.

Out east, as the far end of Long Island is known to locals, duneland and beach grass didn't stand a chance. The sea swallowed half a dozen homes along Dune Road in Westhampton Beach, and residents of low-lying areas, such as Gerard Drive in Springs and Lazy Point in Amagansett, evacuated their homes because of rising water. In Sag Harbor, the water went all the way up to the front door of the American Legion. The Dory Rescue Squad, experienced ocean fishermen wearing bright-orange life vests, evacuated nine Cape Gardiner residents using the same type of plywood boat made popular by prior generations of whalers and haul-seiners (a type of fisherman who used a dory to haul nets out to sea and a truck to pull the nets back to shore). It was the worst squall to hit eastern Long Island since the notorious Ash Wednesday Storm of 1962.

In New Jersey, powerful gales buckled the Atlantic City boardwalk and torrential rains flooded casino lobbies. Blizzard-like conditions blanketed Connecticut in 18 inches of fresh snowfall. Farther north, two Massachusetts residents lost their lives as the weather made landfall. A fallen electrical wire and a tree falling on a van were to blame.

On Cape Cod, 80-mile-per-hour winds blew the Eldia, a 473-foot steel freighter, ashore; the Coast Guard evacuated its 23 crewmen via helicopter. The savage, unnamed storm, which meteorologists described as a "springtime freak," toppled the Great Point Light on the northernmost tip of Nantucket Island. The force of the 1984 gale reduced the stone lighthouse, built in 1818 on the site of the original 1784 light, to a pile of rubble.

Once morning dawned and President Ronald Reagan assessed the damage, he pledged federal disaster relief. But the boys aboard the Wind Blown were still out. They were in the fight of their lives.

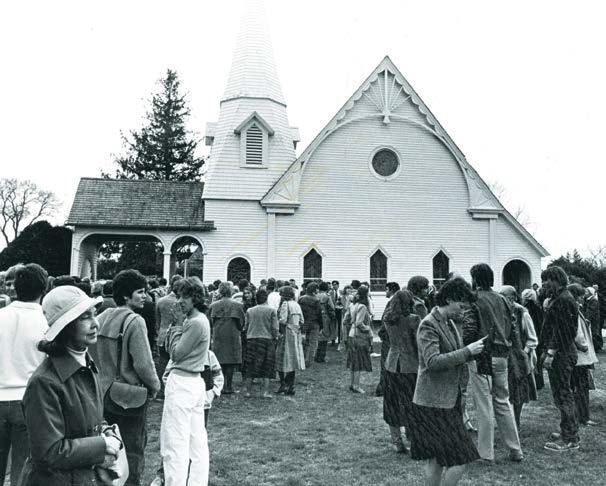

On Thursday, March 29, Chuck Weimer was safely back home in Montauk. He noted in his logbook that hurricane-force winds had picked up, blowing east to northeast at 50 to 75 miles per hour. Offshore, the sea's surface became unreadable through blowing spray and foam. "Did not sail," Chuck wrote in all-caps of the fateful day that he, and so many others on the East End, have since committed to memory. "Wind blown went down or is lost. Really bad news."

Richard Stern, the captain of the Donna Lee, a dragger, last spoke with Mike Stedman on a VHF radio early Thursday, around seven o'clock in the morning, from the comfort of his Montauk living room. Mike sounded relatively okay, despite the horrific winds and 30-foot waves. He conveyed a sense of optimism. Richard expected the Wind Blown to roll into Montauk no later than 11 o'clock that morning.

Standing six-foot-seven, Richard was a legendary fisherman. His hands were the size of baseball gloves. He predicted the weather using two techniques: looking up at the sky and reading his barometer. Over the years, Richard had lost two trawlers to weather-related incidents. Earlier in the week, he had rightly forewarned members of the Montauk fleet that a storm coming up from the Carolinas spelled trouble: "I don't give a fuck what the weatherman says. It's a major storm. People are going to die."

Mike's call to Richard around 7 a.m. placed him 12 nautical miles south of the Midway Buoy, the marker dividing the 14 miles of ocean between Montauk Point and Block Island. Richard assumed the Wind Blown was navigating the deep water south of the buoy. "Deep water is safer in bad weather because there is less chance a boat will be hit by large or unexpected waves," The East Hampton Star wrote in one of its two front-page, above-the-fold stories, which ran the following week. The boldface headlines read: "Fishermen Feared Lost in Storm Off Montauk" and "The Town Is Battered."

Kevin Maguire, captain of the Pontos, spoke with Mike on channel 67 of a two-way VHF radio late Wednesday night and again early Thursday morning. Mike had just hung up with Richard Stern. Gale-force winds and crashing waves were hammering the Wind Blown from all directions.

Depending on sea conditions, tilefishermen usually made it back from the canyons in 12 to 18 hours. By Thursday morning, the Wind Blown crew had surpassed 24 hours in transit, finally approaching Montauk when the northeast wind and rising tide were perilously at their highest. At the time, Mike told Kevin that the Wind Blown was about a dozen miles southeast of Montauk Point. A natural-born stoic, Mike was letting Mother Nature run her course. What other choice did he have?

Captain Mike possessed the hard-won bravado of a man who had successfully charted the exact same course dozens of times before. The trick was staying steady and calm. Panic was for amateurs. Once he made it home to East Hampton, sitting on his couch with a cold pint of beer in hand, the whole thing would make for an epic story. It was a tale as old as time: a young, heroic captain had faced the inhumanity of the sea — and persevered.

But early Thursday, Kevin heard something in his friend's voice he had never heard before. Mike's voice trembled when he spoke.

"Please tell my wife I love her," Mike said.

"Mike, you're going to come in and tell her yourself," Kevin responded.

It was the last time anyone heard Mike Stedman's voice.

When Mike Stedman went off to sea, he left behind his wife, Mary, and their three sons: Christopher, William, and Shane. The past few years of the couple's marriage had been rocky ones — the arrival of three boys in nine years, the emotional and financial strain that raising young children places on even the strongest relationships. The relentlessness of his work, and his frequent absences, had driven an undeniable wedge between husband and wife. Of the pair, Mike was the anchor, the stable, reliable parent.

Dave Connick's last few conversations with his mother, Alice, had been strained. She had frequently expressed her disapproval of the dangerous work her son had chosen. But life at sea fed his restless, fearless soul, and he refused to back down. Upon his return, he also had plans to meet up with his girlfriend, Catherine Cederquist.

Scott Clarke had been raised by a single mother. For years it had been Donna and Scott against the world. Scott had left home at 14, and a pack of commercial fishermen had become the father figures he never had. Scott needed to test out his sea legs. He'd promised his mother that he'd be careful.

Michael Vigilant, too, had a single mother waiting for him back at home. Maude had been widowed six years earlier: her fisherman husband drowned in November of 1978 in the Gulf of Mexico. Like his father, Michael had never learned to swim. After Michael proposed to Kim, he had asked her to wait for him until he came back. It was impossible to imagine that Michael would never pull into the docks again, his jean jacket smelling sweetly of fish scales.

Copyright © 2021 by Amanda M. Fairbanks. From the book "THE LOST BOYS OF MONTAUK: The True Story of the Wind Blown, Four Men Who Vanished at Sea, and Survivors They Left Behind" by Amanda M. Fairbanks published by Gallery Books, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Printed by permission.

See the rest of the June 2021 issue of EAST here: