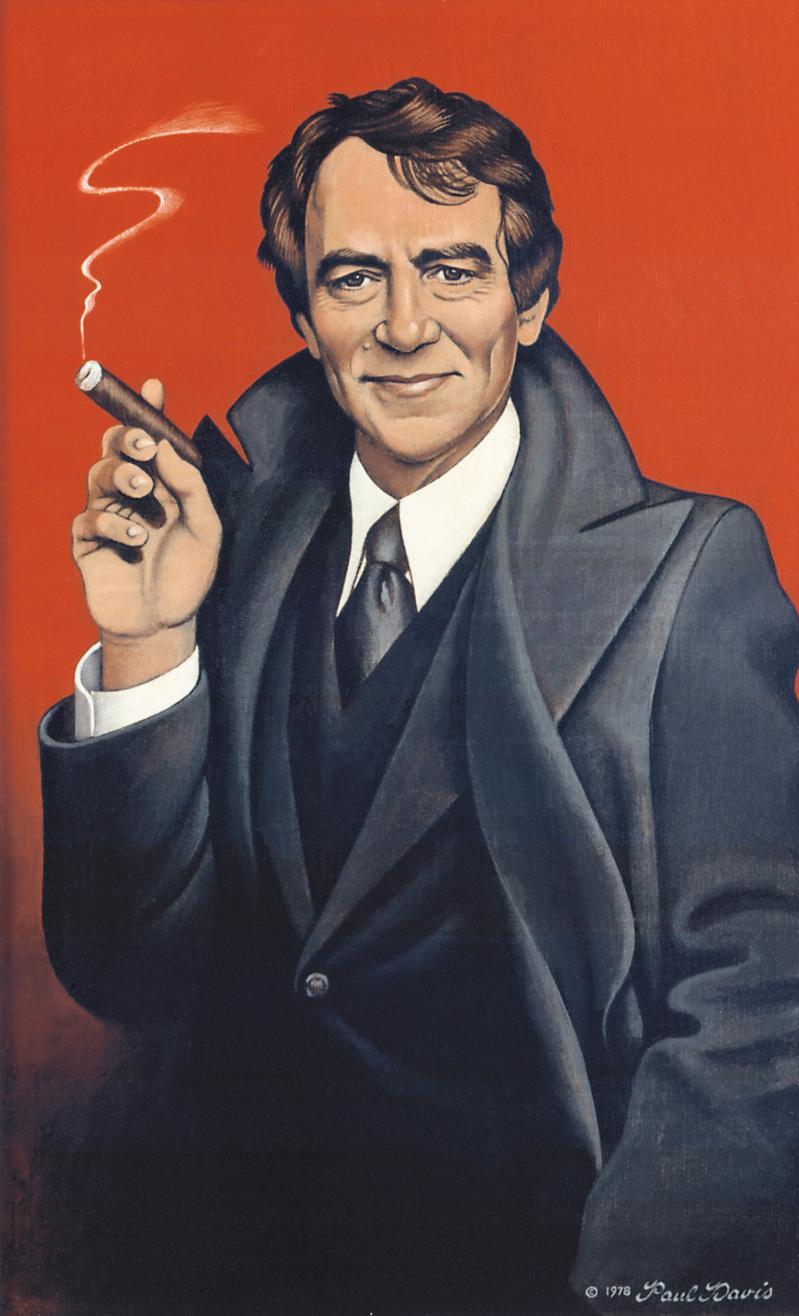

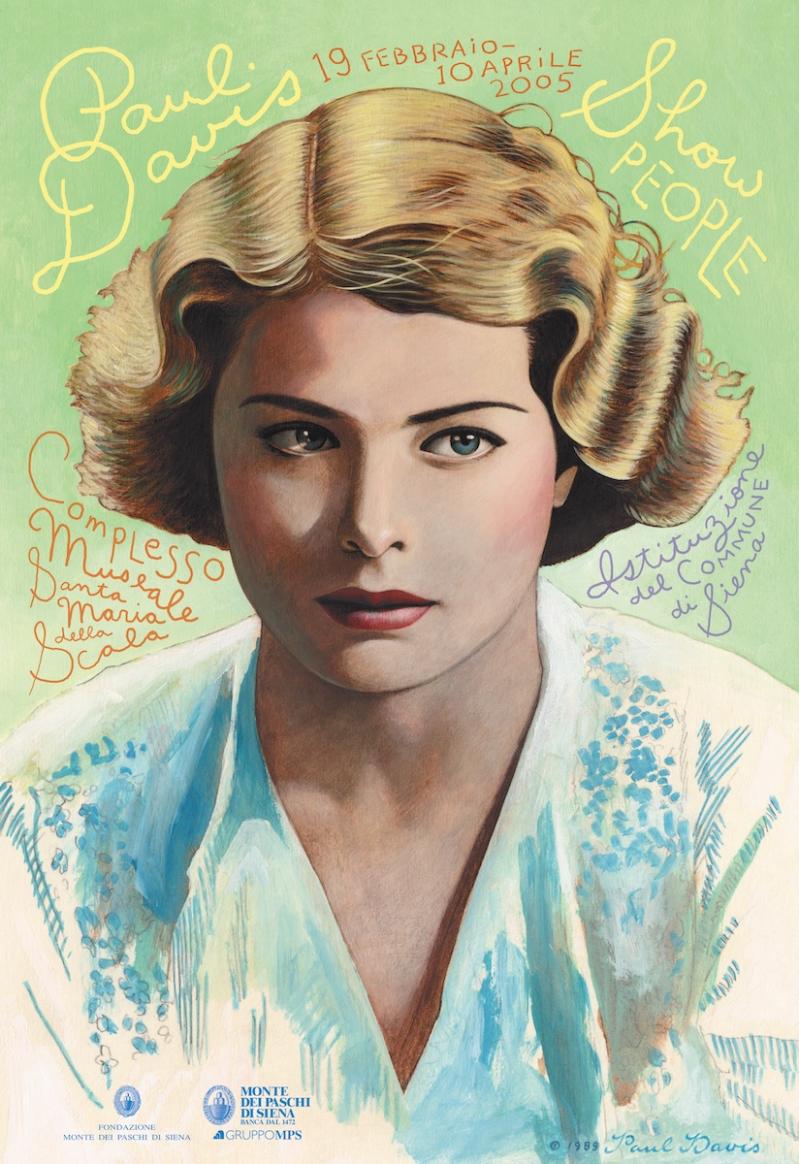

There are already hundreds and hundreds of them — posters for plays, music albums, magazine covers, films, festivals, and ad campaigns, which play with light and lines and color to announce, inform, evoke, and invite, and which were once praised by Kurt Vonnegut as “theater itself” — and there are even more to come.

An already distinguished career has come full circle for Paul Davis, the celebrated artist and graphic designer whose work for the Public Theater and the New York Shakespeare Festival is his most iconic: His latest commissions are a return to Shakespeare and the classics at Theatre for a New Audience, the Brooklyn-based modern-classic performance company.

At Theatre for a New Audience he has picked up where the legendary Milton Glaser left off upon his death in 2020, “which is very intimidating, because he was an incredibly good designer, very versatile, and was much quicker than I am,” Davis said recently in an interview at home in Sag Harbor.

Glaser himself wrote in 2006 that Davis “is one of the artists who has helped define contemporary posters. His significant body of work has made a mark on the culture we all share.” Davis himself, however, has not really considered what impact his own work has had.

“I don’t think I set out” to have an impact, he said. “I just liked the idea that the work was seen by a lot of people.”

Once, during lunch with Glaser, “I said, ‘I worry sometimes about trying too hard to please people, ’ ” he recalled. “What I meant was I felt like I had to follow my inner voice and not cave in when people were trying to get me to do something or change something or do it in a particular way.”

It was that outwardly gentle but inwardly determined spirit that first brought Davis, now 84, from Tulsa to New York City at the age of 17 after high school graduation. He had a cousin in New York who gave him a taste for what a social life could look like, and he had started studying at a cartoonists’ and illustrators’ trade school. The United States Army came calling, but later, Davis would return on scholarship to what had just been rebranded as the School of Visual Arts.

Speaking of the School of Visual Arts, a new poster by Davis celebrating its 75th anniversary is on display right now in the New York City subways. His work is also the focus of a current exhibition at the Museo Archivio Grafica e Manifesto in Civitanova Marche, a town on the east coast of Italy.

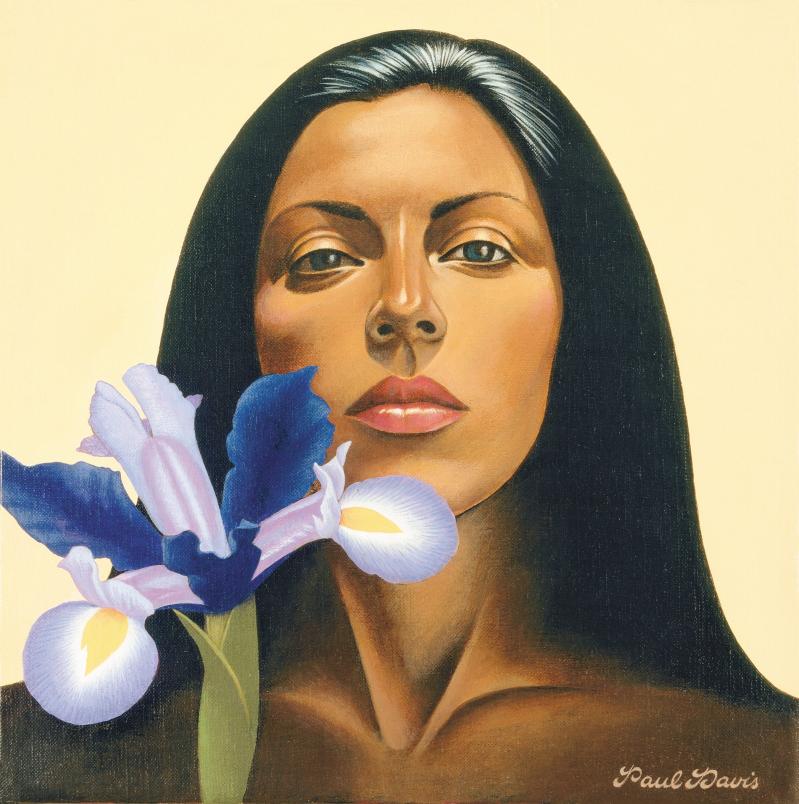

According to Davis’s most recent biography, written by his wife Myrna, a number of his early works were “painted on wood in a distinctive style that emerged from his Oklahoma roots, alchemized with his discovery of early American painting, Surrealism, and Pop art in New York. . . . Working in a variety of media and styles, using acrylic paint, collage, assemblage, wood, metal and papier-mâché, photography, and digital animation, Davis prefers content and inclination to guide him.”

His first show, at the Delpierre gallery in Paris, was in 1968. Its curator, Gilles de Bure, became a lifelong friend. Davis’s work was later selected for a show at a department store in Japan, then for the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, and then for a traveling exhibition in Japan that also had Davis giving lectures. Seemingly everywhere he went, he met people in influential places who took a liking to his work and helped usher his career forward. He and his art have interacted with kings, queens, presidents, and celebrities.

“All these things were happening that were building on each other, but it was just luck,” he said.

Davis was the founding art director of two magazines, Wigwag and Normal, and art director for the inaugural exhibition of the Museum of the Moving Image. He has taught classes and lectured around the world. He was a beta-tester for the earliest versions of the soon-to-be-indispensable graphic design software called Photoshop.

Davis’s most instantly recognizable work is that done for Joseph Papp, founder of the Public Theater, from 1974 through Papp’s death in 1991. A permanent tribute featuring some of his images is on display at the theater on Lafayette Street in Manhattan. He was the designer of the first poster for the Hampton Classic, too, and regularly contributed to festival campaigns for Bay Street Theater. His images are an essential element of the general aesthetic milieu of the East End.

“I think the thing that really makes an artist successful is that the ones that are successful mostly have a narrative — an ongoing narrative through their whole life, in a way,” Davis said last month. “If someone like [Josef] Albers just painted half a dozen pictures of squares, he would never have been considered a great artist, but because he did hundreds, he kept going.”

But Davis does not actually relate to Albers’s personal narrative; instead, his own life story feels a little like a right-place-right-time story. In his own telling, his successes followed naturally from opportunities that happened to present themselves. It began when his talent — a very concrete and obvious talent — was first nurtured by Hortense Bateholts, his art teacher at Will Rogers High School in Tulsa. Are teachers not our very first influencers, after all? “She was so encouraging. She told us all to make portfolios, but she favored the boys,” Davis said. “Whenever you wanted any advice, you’d take your painting up to her. She’d turn it upside down and say, ‘What does that do to it?’ I began to understand a little about composition after that.”

Buoyed by the encouragement from his high school art teacher, Davis knew there was no way he wasn’t going to become an artist. “It was always the idea. What I did, really, instead of doing what everyone said you should do — ‘Go get a college education so when you can’t make a living as an artist, you can teach’ — I sort of burned bridges and went to a trade school. There was so much chance involved, but I was not going to do something else.”

Throughout his career, Davis has had an important partner by his side: his wife, Myrna, whom he met at Push Pin Studios in 1959 and married in 1965. She had been the editor of a publication called Push Pin Graphic and was “very sensitive to the needs of the work,” her husband said.

“Myrna has been a full partner in my life and in my creative work,” Davis said. “She managed our studio, worked with clients, created projects, found new opportunities, always had a wider circle of connections. I could not have had the success that I have without Myrna.”

Davis’s first commercial illustration appeared in Playboy magazine. Soon he was hired at Push Pin, the hottest illustration and design studio of the era; how he got hired there probably wouldn’t fly in today’s culture of corporate gatekeeping. Glaser had already turned him down for a job at Push Pin, but Davis was persistent. “In the fall of 1959, I was offered a job at Good Housekeeping. They said I could start as an assistant but that the assistant art director was going to leave. . . . The next morning, I called up Push Pin. Seymour [Chwast, a co-founder], who was always the first one to get there, answered the phone. I said, ‘I just got a job offer from Good Housekeeping and if you don’t hire me, I’m afraid I’m going to have to take it.’ And that’s how I got hired.”

Davis is the kind of artist who never feels that a work is complete — even after he’s met his deadline for a particular project. If given the time, he would just keep going and going until he gets a feeling that it’s finally done. “The thing that surprises me so often when I finish a picture, I’m disappointed or feeling a little sad because it didn’t come out quite the way I wanted it to.”

Making art is “like going underwater. I enter another mental state and I do the work and lose track of time.”

In a era when “some people were limited by being funny, by being comic, or by the way they drew,” Davis said, “I realized I wanted to make a style that was so expandable that I could work on any subject in the same way, and I wanted something that was very flexible but true to whatever the vision was.”