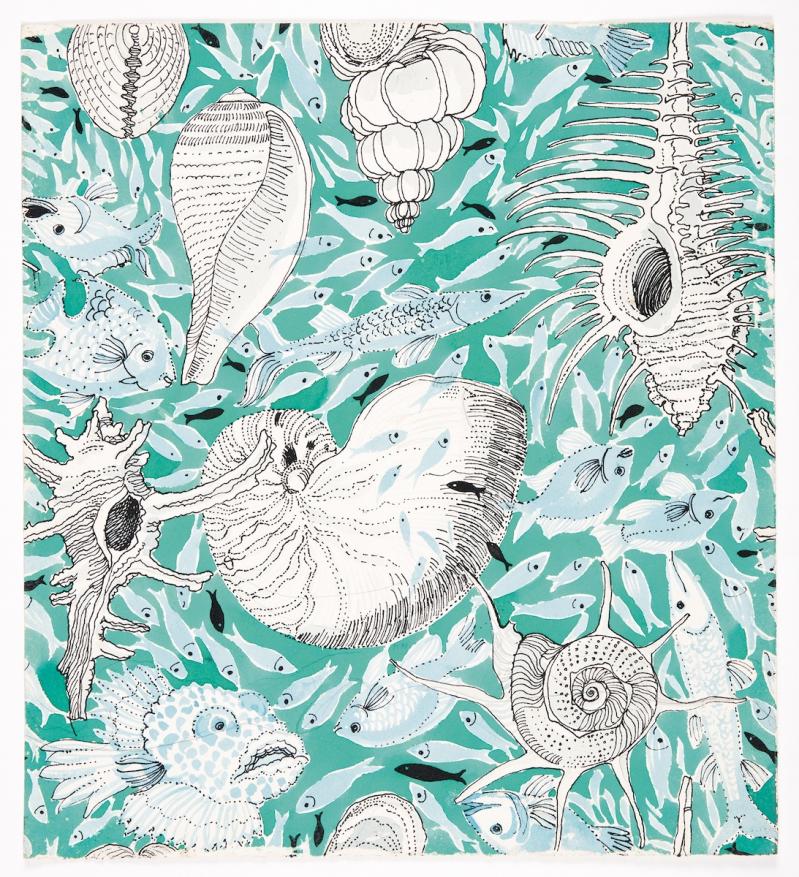

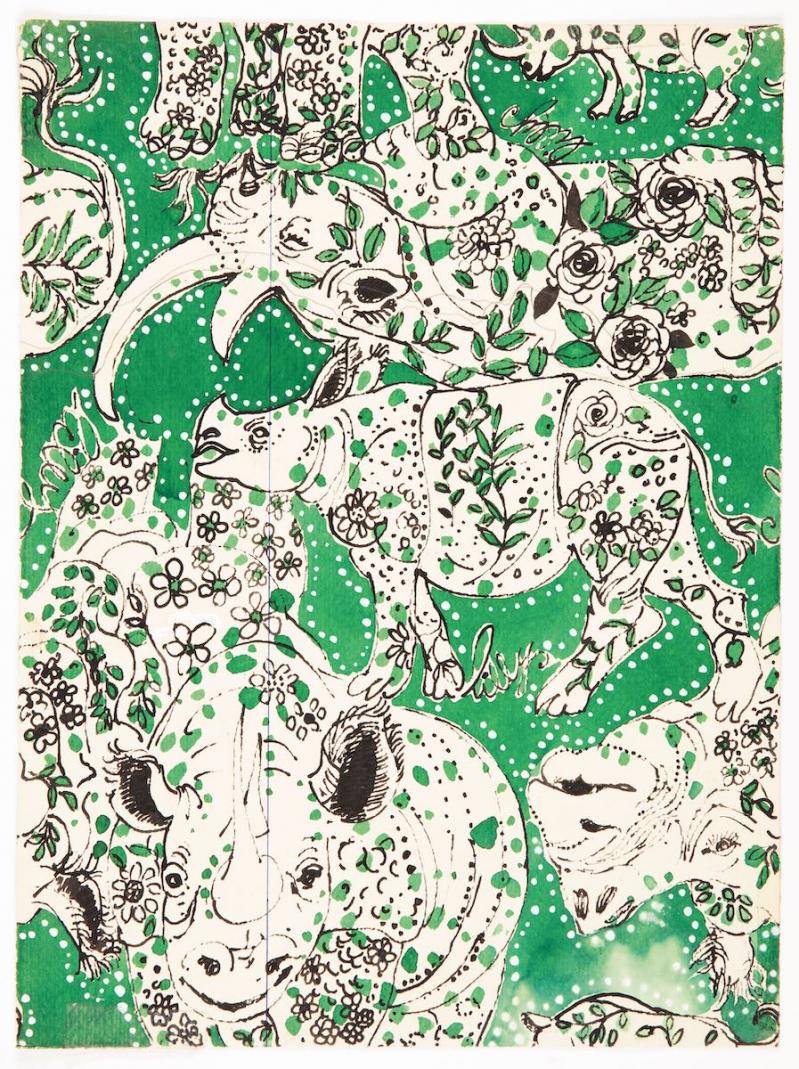

Coco Chanel once said, “People’s lives are an enigma.” That was certainly the case for Suzie Zuzek, a virtually unknown textile designer who depicted audacious, dreamlike worlds on fabrics that became the iconic palette for the Lilly Pulitzer brand — cheetahs lurking around daylilies, monkeys sipping martinis, tongue-in-cheek jungle prints, angelfish, palm fronds, deep-sea landscapes, psychedelic hibiscuses, fruit, penguins, and much more.

Between the 1960s and mid-1980s, Lilly Pulitzer built a fashion empire around what became known as “the Lilly look”: simple, boxy shift dresses, tops, A-line skirts, Bermuda shorts, children’s clothes, and even menswear, all made from Zuzek’s outlandish and whimsical fabrics. Pulitzer’s high-society connections underpinned the company, of course: She was a socialite married to Peter Pulitzer, an owner of hotels and citrus groves and the grandson of the publisher Joseph Pulitzer. Jacqueline Kennedy, who had been a childhood school chum, was, as the First Lady, photographed wearing printed Lilly dresses at Hyannis Port. Other bluebloods — Dina Merrill and Wendy Vanderbilt and even the Duke of Windsor, who owned a pair of Lilly bathing trunks — adored the playful Lilly designs, too. Pulitzer earned the title “the Queen of Prep” and her stores became a staple in upscale resort towns from Charleston to Maine.

But this style story didn’t really begin in Palm Beach. It all began in a rather more bohemian location: at a small fabric-printing business in the Florida Keys called Key West Hand Print Fabrics, where Zuzek — then married to a Cuban-American Key West notable native named John de Poo and known around the Keys by the unforgettable name of Suzie de Poo — created some 1,500 highly saturated, fantastical designs for the Pulitzer label over a span of 25 years.

Zuzek, by all accounts, was a rather extraordinary person. She was born Agnes Helen Zuzekin in 1920 to Yugoslav immigrants who lived on a dairy farm outside of Buffalo, N.Y. She served in the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WACs) during World War II before attending the Pratt Institute in New York City under the G.I. Bill and then started her career in the Garment District in Manhattan. She and her husband, John, moved to Key West in the mid-1950s and it was there in 1962 that Pulitzer, having come across some of Suzie’s work, found her working on salary at the textile shop. Pulitzer bought Suzie Zuzek’s fabrics exclusively for the next 15 years, building her brand around their “it’s always summer somewhere” ethos.

Textile designers were, until very recently, largely unsung heroes of the fashion industry and Zuzek was no different. She remained anonymous, her work unattributed during her lifetime. Even when Pulitzer died, in 2013, her obituary in The New York Times offered no credit to the creator of the prints — perhaps the most famous prints in all American fashion history —and no mention of Zuzek’s name or her influence.

Zuzek tried on many occasions to request royalties for her work, but she never received anything more than a base wage. She died in 2011, at 91, without recognition for her enormous artistic talent and without much money in the bank.

Her story could have gone untold, at least beyond her Key West community, had it not been for an exhibition called Suzie Zuzek for Lilly Pulitzer: The Prints that Made the Fashion Brand, which ran last year at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in Manhattan. Finally, the true force behind the Lilly Pulitzer look was revealed. Susan Brown, the associate curator of textiles at the Cooper Hewitt and the organizer of the show, also coauthored a book about the designer titled, Suzie Zuzek for Lilly Pulitzer: The Artist Behind an Iconic American Fashion Brand, 1962–1985.

In an article in W Magazine last year, Brown spelled out the significance of the show: “Suzie Zuzek is somebody whose work is familiar to millions of people, and who had a major impact on the social history and the material culture of the 1960s and ’70s, but most people have never heard her name. Textile designers are so rarely credited for their contributions to fashion. I think it’s a story that will be really relatable to a lot of creative people who work anonymously,” she said.

Not surprisingly, Zuzek was not well known on the East End, either, even though the brand has been a seasonal presence since 1964, when a Lilly Pulitzer boutique opened on Job’s Lane in Southampton. The Washington Post reported in 1966 that the look was “so popular that at the Southampton Lilly shop on Job’s Lane they are proudly put in clear plastic bags tied gaily with ribbons so that all the world may see the Lilly of your choice. It’s like carrying your own racing colors or flying a yacht flag for identification.” There was another Lilly Pulitzer store on Newtown Lane in East Hampton for many years, and the Ladies Village Improvement Society held a Lilly Pulitzer fashion show at the annual fair in 1969.

Unbeknownst to almost everyone, Zuzek herself had a strong East Hampton connection. Her husband, John de Poo, left her and their daughters in the late 1960s and began to shuttle between Key West and East Hampton, becoming part of what was then a young, dynamic community of creative people who flocked here to meet other creative people. He is remembered as a true character, legendary in some circles for his adventurous and nonconformist spirit. Judith Hope, who was elected East Hampton Town supervisor in 1973 — and went on to become the chairwoman of the Democratic Party in eastern New York State — was a longtime friend of de Poo’s, and she remembers him speaking about his marriage to Zuzek. According to Hope, it was a union of “two extremely original human beings.”

John de Poo had served dangerous duty in the Merchant Marine during World War II and, according to a profile in The East Hampton Star, later worked variously as bakery instructor in the U.S. Army, a carpenter, deputy sheriff of Monroe County, Fla., a weaver, bartender, and Key West City commissioner, as well as being an actor, pioneer of the sport of windsurfing, and even — if you believed him — circus performer. He was also an accomplished chef who, in his decades on the South Fork, threw epic dinner parties at which tales from his colorful past unfolded. “He told many really amusing stories about Suzie. He clearly had enormous admiration for her talent, but I think the two of them living together was a bit of a circus,” Hope said in a recent interview, laughing at the memory. “Because they were both eccentrics.”

Hope herself now divides her time between East Hampton and Key West. She heard hundreds of stories about Zuzek from de Poo, and has visited the late designer’s house in Key West, where Zuzek had created sculptures and ceramics after retiring from textile design in 1985. (The house is still used for art events and studio tours on occasion.)

Hope continued. “John told a story about Suzie — that she collected many things. Not only objects, but human beings as well, and that it was not at all unusual to come home and find some stranger sitting at the dinner table or the breakfast table. He recounted one time that he woke up and went downstairs to the kitchen and there was a little old lady sitting at the breakfast table. And he said, ‘Suzie, who is that?’ And Suzie said, ‘Oh, John, isn’t she adorable? That’s Mildred and she needs a place to live for a while.’ Well, according to John, three years later, she was still there. Still in the kitchen at every meal,” Hope recalled.

“And she collected animals. So, any stray animal — he said she just could not leave a stray animal left behind anywhere. She immediately picked them up and brought them home. So it was a bit of a menagerie.”

Indeed, according to Keys Weekly, which published a Zuzek profile based on interviews with the de Poo daughters last year, after the family settled into a large house on Dey Street, she created a genuine menagerie “that at various times included a red-and-green macaw, an alligator, raccoons, a horny toad, a donkey, peacocks given to her by Janet Reno’s parents, and a squirrel monkey that had a tendency to escape and explore the homes of other families. She also took care of fellow artist Henry Faulkner’s goats when he was out of town. There may also, at some point, have been a bobcat.”

Like most true artists, Zuzek was, by all accounts, a complex person, and that complexity is reflected in her whirling and interlocking motifs, which may be the quintessence of American summer casual but are actually multilayered, precise, and masterful. Her flora and fauna radiate sunshine and warmth — and the fact that she is finally being recognized warms the hearts of those few who knew, all along, that it was she.