There is an artifact that is now housed in the Long Island Collection at the East Hampton Library — framed, and hung on the wall behind protective glass — that dates back 323 years. It measures just under four-and-a-half inches long and less than half that high. It is only a small fragment of cloth, woven of silk, cotton, and metallic gold and silver thread. Yet, this remarkable remnant of sumptuous silk is the very stuff of pirate legend.

On June 27 of 1699, an unexpected visitor came to Gardiner’s Island, which at the time was known as the Isle of Wight. Captain William Kidd anchored his latest acquisition, the six-gun sloop San Antonio, in Gardiner’s Bay and summoned John Gardiner to bargain for cider, sheep, and other supplies. Depending on whose side you take in a centuries-old argument, Kidd may have been a pirate — or he may have been a privateer sailing, as he had during a long and illustrious career, under letters of marque from the British Crown and legally stealing from the enemies of England.

Kidd came to Gardiner not just to provision his sloop, but to leave behind three enslaved children and his treasure, for safekeeping.

The treasure was taken from the ship Quedagh Merchant 18 months earlier off the Malabar Coast of India. That ship, heavily laden with gold, rubies, and emeralds, was an Indian merchant vessel that Kidd plundered and took as his own, renaming it the Adventure Prize and setting sail for the West Indies.

As Kidd later recounted in a confession, when he arrived at Santa Catalina in in the Dominican Republic he heard that he had been accused of piracy, so he burned and scuttled the Quedagh Merchant and bought the San Antonia, filling its stores with riches to be used for his own ransom and hurrying north to clear his name. Captain Kidd set his course to New York and the Isle of Wight.

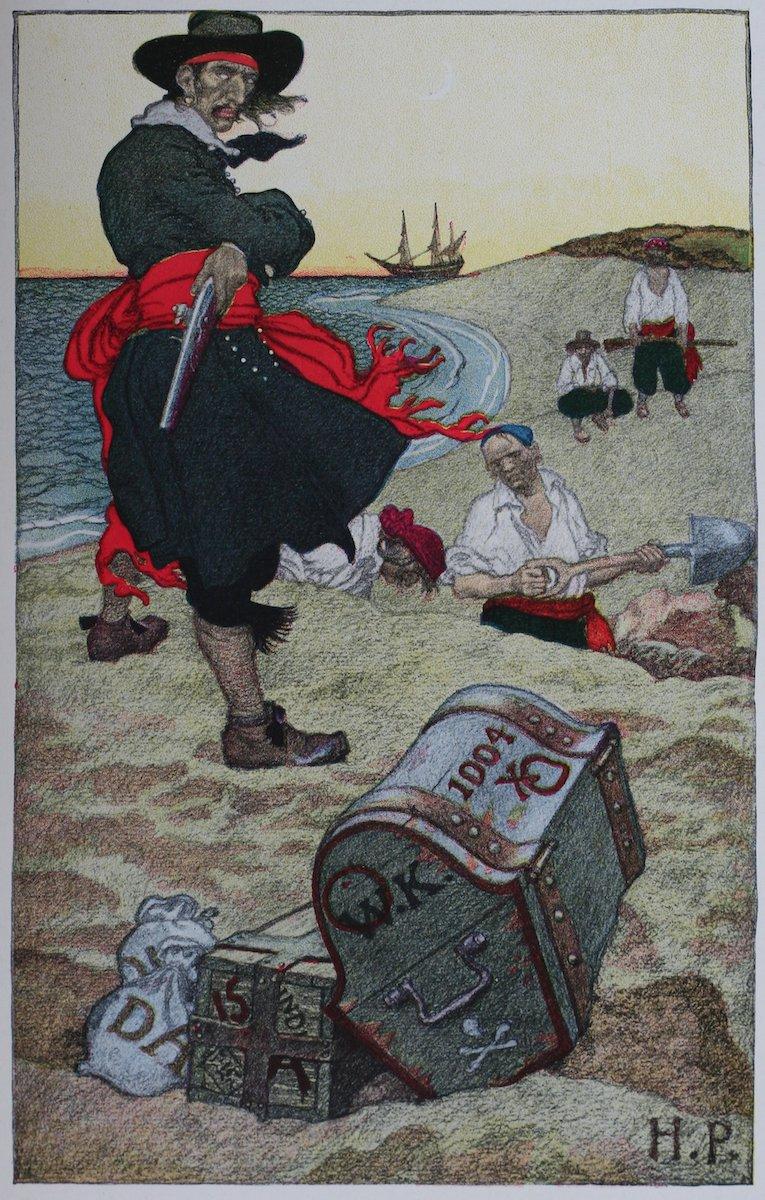

In the story that came down in the Gardiner family, Kidd broke into the manor house at night, destroying featherbeds with his cutlass, hiding his treasure in the swampy area of Cherry Harbor, and exiting with a threat. According to the archival papers of the seventh proprietor of the Island, Kidd showed “Mr. John” — that is, Gardiner — where he had stashed the treasure and told him, “If he never come for it, you may have it . . . but if he called for the treasure and it was gone, he would take Gardiner’s head or his son’s.”

As retold in The East Hampton Star in 1914, “Kidd added, ‘I wish your wife would prepare me a small roasted pig.’ This the lady, with great fear and trembling, hastened to have done, and so well cooked was the meal that Captain Kidd sent Lady Gardiner a blanket of cloth-of-gold, parts of which have always remained in the family.”

But Kidd, having been accused of piracy by the Crown, soon left Gardiner’s Island for the Port of Boston to clear his name. It is said he fired off a four-gun salute as he departed.

Parts of the Boston court depositions survive. To Kidd’s surprise, he was arrested and imprisoned in Boston to await transport to London to stand trial for murder and piracy. The treasure left at Gardiner’s Island for safekeeping was listed in that deposition and an escort of court officials was sent to confiscate it. It was dug up by the officials with Gardiner’s assistance and meticulously inventoried to be entered as evidence in Captain Kidd’s pending trial under English maritime law.

One item, however, went missing after the inventory was made: not the cloth of gold, but a large uncut diamond. One account states that it was later found in Gardiner’s portmanteau, but there is another more colorful story from the Gardiner family that tells a more elaborate — and possibly apocryphal — tale: Before the commissioners left, as it was described in 1919 in The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, “Mrs. Gardner, in a playful way, said she wanted to have it said [that] she had held so much treasure, and the jewelry was poured into her lap. After they” — that is, the commissioners and Lord Gardiner — “had left for Boston, a bright stone was found on the floor, and picked up by her. When her husband returned, he found it to be a diamond.” His wife convinced him to keep the jewel, saying she would risk the consequences. In this version of the story, it was eventually cut and set into a ring for the lady of the manor, who got her way in the end. According to this account, the ring remained in the family up through the late 19th century and was last known to be in the possession of Mrs. Jerusha Gardiner of Stonington, Conn. Now, no one knows where it is. The ring has been reclaimed by history, swept away by the tides of time.

On May 9, 1701, Captain William Kidd met his destiny in the Admiralty Sessions held by His Majesty’s Commission at the Old Bailey. The life of this Scotsman-turned-New Yorker — a man who owned properties in Lower Manhattan and lived on Pearl Street, who had two daughters, and kept a pew at Trinity Church — would end at the swinging end of a coarse hemp rope.

Our captain was escorted to his execution place by a throng shouting jibes and jeers. Some in the crowd offered a compassionate cup of comfort as he made his way to his final destination. He supposedly arrived completely inebriated and was greeted by a disapproving clergyman who mumbled a few prayers as Kidd was led up to the gallows. Given the opportunity to speak his last words, according to The Newgate Calendar (a contemporary catalog of rogues and their inglorious ends), he professed “his charity to all the world, and his hopes of salvation through the merits of his Redeemer.”

The rope was fitted around his neck — but there was to be no short, sharp shock from the hangman’s noose. It was a slow, gurgling, gasping garrote. The stool was kicked out from under his feet. The crowd, anticipating the “dead man’s jig,” instead was surprised when the rope, rotten, broke away and Kidd tumbled into the mud of the Thames. The crowd gasped and Kidd declared that this was an act of God, proving his innocence.

But the shadow of the gallows fell across him while a new rope was found. He died a slow, excruciating death, and his body was chained to a piling at Executioners Dock so that three high tides would ebb and flow over his remains; this was what the law decreed for those convicted of piracy.

On the third day, what was left of him was slopped with tar and fitted in a gibbet and hoisted high, so his bones would cry out “Pirates beware!” to every ship arriving at and departing from the great city of London.

The confiscated treasure used as evidence against Kidd — minutely detailed down to the last bar of gold, uncut sapphire, and broken silver candlestick or lamp in the receipt presented to Gardiner by the agents of King William — was never returned to its rightful owners.

According to the recorded deposition of John Gardiner, the booty he personally witnessed being unloaded from the sloop included “damnified muslin and Bengals” cloth that had been given to his wife, Lady Gardiner, as a present; “a Chest, and a Box of Gold, and a Bundle of Quilts, and Four Bales of Goods,” as well as “Two Bags of Silver” weighing 30 pounds, “a Small Bag of Gold and Gold Dust” weighing about a pound, “and a Sash, and a Pair of Worsted Stockings” presented to the lord of the manor as personal tokens of thanks.

While in prison, Captain Kidd had alluded to even more hidden stores of stolen riches.

And so for centuries those bitten with the gold bug have searched worldwide, many focusing on Long Island and the Hudson Valley, for his booty. Some have lost family fortunes investing in salvage schemes.

The tale of Captain Kidd and his connection with the East End doesn’t really end with his hanging. Generations of local children have set off treasure hunting along the beach of Gardiner’s Bay, scouring the pebbly shoreline in spots where you can stand and see Gardiner’s Island — the sweep of the bay from Promised Land and into Springs. And the cloth of gold hangs in repose in the East Hampton Library, a remnant of a gory and yet captivating story.

In 1932, a reporter for The Star noted that the small remaining scrap of the gold-threaded fabric was still held by the Gardiner family. In 1937, it was exhibited at the East Hampton Library on the occasion of the library’s 40th anniversary. We don’t know what year it was formally donated to the library, but it was noticed on display there in 1942 and again in 1956 and 1958, so, by process of deduction, it appears to have entered the permanent collection in the 1930s. In 1961, Robert David Lion Gardiner, the then-current lord of the manor, borrowed it back to show it off — along with one of Kidd’s pieces of eight — at the annual banquet of the Bridgehampton Historical Society, held at the Huntting Inn.

Meanwhile, time and tide have revealed the greatest treasure of all: The Quedagh Merchant was discovered in 2007, remarkably undisturbed, in shallow waters off the coast of Catalina Island in the Dominican Republic. The long-lost wreck is now a “Living Museum of the Sea,” a “no take, no anchor” wreck site that protects both the maritime history and the biodiversity of the area’s coral reef.