It’s 3:30 in the afternoon on a late-spring Friday at East End Stables, and Ava Lynch is tacking up her horse, Toby, after wrapping up a typical schoolday at Pierson High School in Sag Harbor. The steps are second nature for Ava, who has just turned 15, and who applies a youthful matter-of-factness to her tasks. In 18 minutes she’s got Toby groomed and saddled; she straps on her helmet and leads him into the indoor training ring.

The ring itself has a palpable venerability to it, with its soft, fragrant dirt and several adjustable-height fences for jumping. Here, riders like Ava know dusty boots and gloves and hair pasted to sweaty foreheads under helmets are all hallmarks of hard work. She trains three to four days a week with Andre de Leyer and Christine de Leyer, the couple who own the stables, and Jen Santacroce. Andre de Leyer is a son of the late Grand Prix rider Harry de Leyer, a show-jumping legend here and abroad, who died in 2021 at the age of 93.

Ava never had the chance to meet the Galloping Grandfather himself, though he would have approved of the reverence she holds for horses and of her dedication to her English riding studies at the barn he originally bought sometime around 1980.

“I think he’d think she was a hard-working student,” Andre de Leyer said. “That’s what he loved in children.”

Ava and Toby start with flat work, a warm up consisting of slow laps and easy changes in direction. After about 10 minutes, they pick up the pace. “Okay, Ava, let’s trot,” says Andre, as a couple of pony-camp girls look on with someday-that’ll-be-me looks on their faces.

“Okay, we’ll get the long trot now,” he calls a few minutes later to his student, who’s busy ignoring everyone and everything else around her. “Check your rein line,” he adds.

Then comes jumping practice. The focus is on balance, rhythm, and equitation (defined as “the art of horsemanship”), and on knowing the horse itself. It’s not every day; sometimes Ava “hacks” Toby, meaning a session of walking, trotting, and cantering as exercise for both rider and horse. And after each half-hour private lesson, they saunter out of the barn and into an outdoor paddock for a little downtime and some grazing (Toby, not Ava).

Ava takes particular care in the un-tacking process, “which is important for the connection” with the animal, she says as she brushes away the dust. “A lot of barns have people who do it for you, but here you do it all yourself.”

The de Leyers’ three corgis, Bella, Momo, and Mister Bear, scamper freely around the barn as Ava lays a blanket on Toby’s back and offers him his first-ever pear — which he eagerly devours, covering Ava’s hand in saliva. She leads him into his stall and gives him enough pats and goodbye kisses to last two days, until the next time they’ll see each other.

Meet Toby

First of all, it’s important to know that Toby is his barn name. When it’s time to compete, the judges know him as Bay Street, a name that is significant to the Lynch family, who currently live in Wainscott.

Ava’s great-grandfather, George Cary, lived in a house on Bay Street in Sag Harbor; her grandmother, Suzanne Cary, grew up with five sisters there. George Cary rode in Montauk and even competed in rodeos when he was young, winning first prize in the bronc category on Oct. 26, 1940, at Madison Square Garden. The family found the trophy cup when they were cleaning out the Bay Street house, getting ready to put it on the market.

Melissa Lynch had the trophy cup polished up and presented it to Ava on Christmas Day in 2021, when Melissa and her husband, Gerard Lynch, told Ava they would be buying Toby for her.

Toby weighs between 1,500 and 1,600 pounds and stands 17 hands tall, or, fig- uring that one hand measures roughly four inches, he’s about 5-foot-8. He’s what they call an “easy keeper,” with good ground manners. “I think he has such a puppy mentality,” Melissa says. “He’s like a big Labrador retriever.”

He likes snacking on apples, vegetables, strawberries, bananas, and frosted sugar cookies, but he did not seem to enjoy the taste of Ava’s iPhone that time he grabbed it out of her hand and took a bite.

On Thursdays, one of two days that the barn is closed to the public, Andre de Leyer trains Toby so that he doesn’t pick up any bad habits. “He still has baby or toddler-ish behavior sometimes,” Ava says.

Trot Before You Canter

It all started, as it has for so many young riders, with a day at the Hampton Classic in 2018. Ava, who hadn’t shown interest in riding before that, decided she wanted in. “It doesn’t feel like that long ago,” she says.

An eager tennis player at the time, she was 12 years old, which some will say is too late for a serious competitor to start a brand-new practice, but that’s what they told Misty Copeland, too. (The American Ballet Theater principal only began studying ballet at 13; the rest is a lesson in perseverance.)

When Covid-19 closed schools for several months beginning in March of 2020, riding “helped my mental health,” says Ava, whose family was leasing her a horse named Fred at the time. “It’s a big part of my life.”

“It keeps you disciplined,” Melissa Lynch says.

“It keeps me responsible,” Ava adds.

Her “favorite sound in the whole world,” she says, is the slow but satisfying clop-clop-clop of Toby’s feet on the brick pathways outside the barn after a lesson.

She has made a lot of friends at East End Stables, including at least one who comes all the way from New York City to train with the de Leyers. “The whole barn feels like family to me,” Ava says.

But in committing to riding, there are tradeoffs, like not having time for after-school clubs at Pierson, where she is a sophomore. “It’s a lifestyle,” Ava says. “It’s hard to do other things.”

In addition to the training, there are long hours of traveling: She competes not just on Long Island at places like Wölffer Estate, the Yaphank Horse Series every other week in the summer, and, of course, the Hampton Classic, but also on the wintertime circuit in Ocala, Fla., for the first time this year, and three times a year in upstate Saugerties.

When Ava got her start, she was riding a pony named Dudley. Their very first competition was the youth Hunter division at the Classic.

“We had no expectations,” her mother said, “and she won.”

Dudley died a short time later, and a heartbroken Ava was reluctant to return to the barn. When she did, she was faced with the prospect of graduating up to a horse. Her mother recalls her saying, “ ‘I don’t want to ride a horse. I don’t want to get taller.’ I said, ‘Well, I think you are going to, so you should probably ride a horse.’ ”

They bought a Japanese maple to plant in Dudley’s memory. Its orange foliage each fall would remind Ava of her beloved pony’s vibrant coat. They put the tree in the ground; everyone had a good cry. “Then Chris walked her over into the barn and got her to ride again,” Melissa Lynch said. “It was an emotional time for sure.”

Ava transitioned soon after to the Jumper class, “a totally different discipline from what she was used to doing,” Christine de Leyer said. “Your reflexes have to be fast.”

Game Face

High-level athletes often speak of sacred pregame rituals or mental-acuity exercises to prepare themselves for games or races. But Ava — who aspires to continue competing through college and beyond — says she’s more focused on getting her horse ready than she is on herself.

“Usually, I try not to think about it beforehand,” she says. “I do my best to distract myself until I actually have to go out there. Otherwise, I’ll just overthink it and it will wind up a mess.”

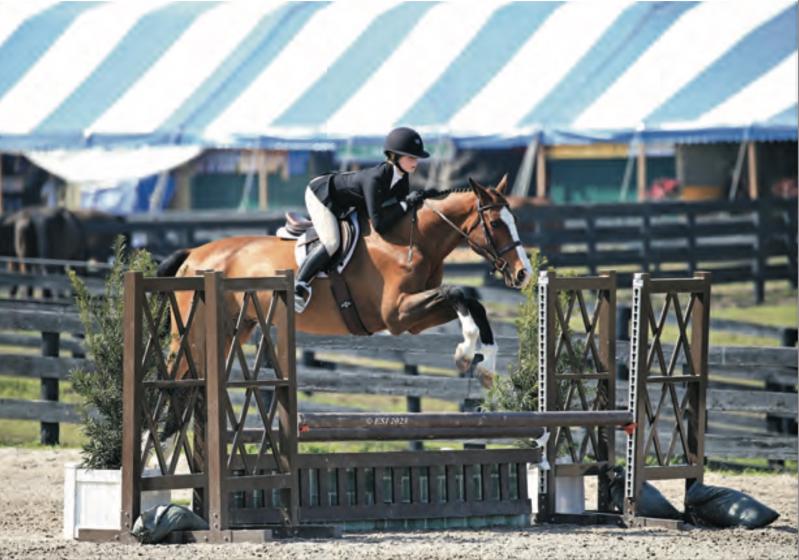

Last summer was the first time Ava rode Bay Street in the Classic and the first time she ever competed on grass. With 40 kids in her class, she landed in eighth place. Fast-forward to Mother’s Day weekend at Wölffer Estate, when she finished in fourth and seventh places out of a field of 15 in the low children’s Hunter class.

The highest jump she and her horse have accomplished thus far was a 3-foot, 3-inch fence. In Florida, where the heat has been known to get to horse and rider, the pair managed a 2-foot-6 jump. “It’s better to go higher at home,” Ava says.

She once fell off her horse. In adherence to the adage, she climbed back up and finished the competition. Later, they learned she’d fractured a bone in her pelvis. Ava, an adventurous sort, was not deterred. Girls who ride “have a little less fear in them than most,” says her mother, who can’t help but hold her breath every time daughter and horse take a leap.

Training is physically demanding, particularly with calf strength, which Ava says is her biggest flaw. “You use almost every muscle,” she says.

A couple of weeks later, Christine de Leyer takes a turn coaching Ava. She says her student is mature and dedicated, with a level of compassion she doesn’t often see in a young person. “That’s a major thing.”

“It’s not just handed to her,” Christine continues. “She shows up. She does all the things that come with this. That’s inner strength.”

She turns her attention back to Ava. “Okay, sister, we’re going to cross, lead change, and stay in the big circle, okay? Big turn, don’t look down. Watch your inside heel.”

So that’s what Ava does.

There’s a myth, she says, that competitive riding “is easy, that anyone can do it, or that it isn’t a sport. That’s just not true.”