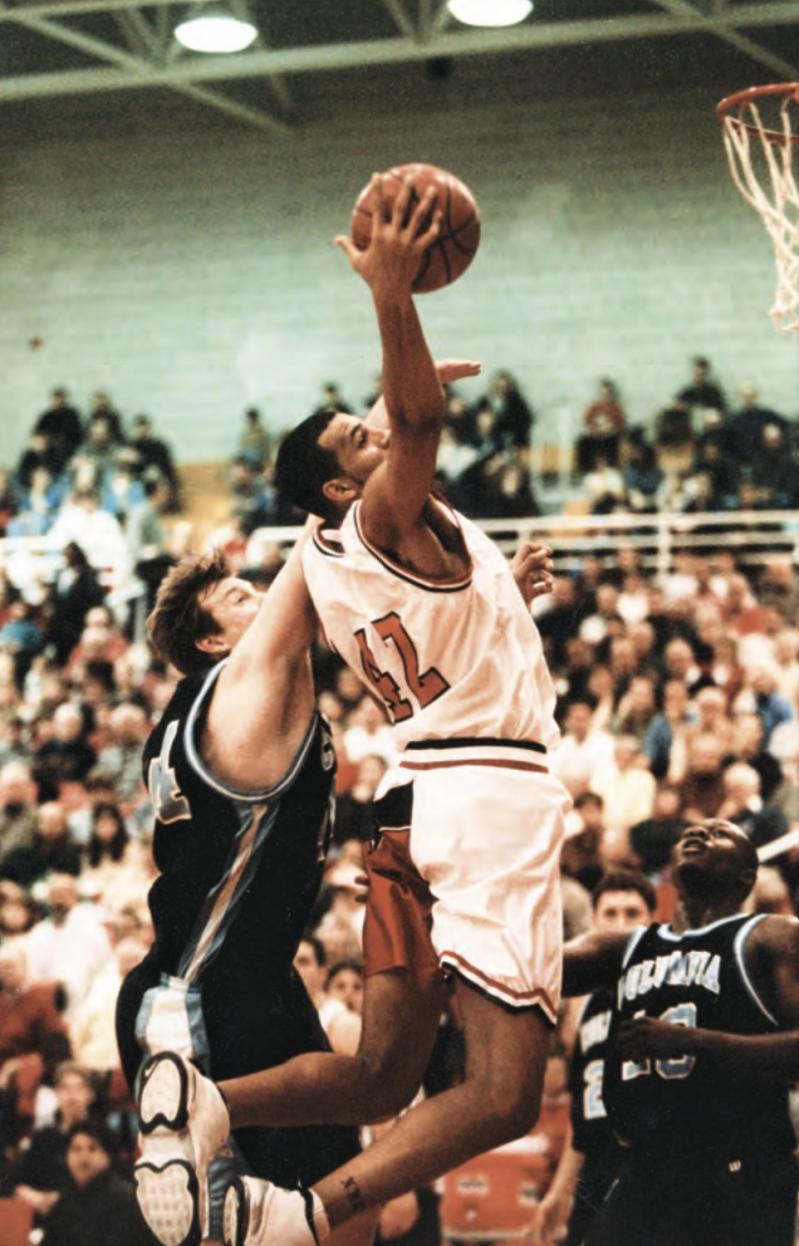

In his days playing Division I basketball at Cornell University, Jeff Aubry was known as the king of shot-blocking. A 6-foot-9 center and power forward, he’d kicked off his freshman year as one of 18 rookies ever to make the starting lineup in his first contest in school history and ultimately topped the Ivy League in season-total blocks — twice.

He graduated in 1999 and went on to play professionally across the globe. Now, the shot-blocking king is a full-time resident of Sag Harbor, and he’s determined not to deny other players shots, but rather, to nurture them — to give them the best possible chance at a meaningful career in pro hoops. In March, he was named executive director of the brand-new Next Gen Basketball Players Union, representing players in the NBA’s development league, where he himself once played.

Officially called the G League, it plays an important role in growing future talent for the NBA and abroad. Aubry, who studied industrial labor relations at Cornell and later earned a master’s in sports management at Columbia University, said he feels honored and excited to step into the role representing the G League players. “The opportunity to be an advocate for them in a much more intentional way that spans not just their off-court development, but their on-court business opportunities, their work-life balance, mental health, and benefits, just fits so well with not just what I care about, but also with my experience and expertise,” he said in an interview.

As of press time in August, labor unions were riding the top of news headlines. The Writers Guild of America had gone on strike, shutting down late-night TV shows and impacting film and TV production across network, cable, and streaming platforms. Starbucks workers continued to actively organize in stores across the nation. And the American Airlines pilots’ union, a pivotal sector of aviation professionals, was organized and lobbying for pay increases and better schedules.

“During Covid, when NBA players had to sit out multiple weeks because of infections, G League players are why they didn’t have to cancel games and why the league was still successful,” explained Aubry, formerly the NBA’s senior director of player development. “That was huge for the league and its revenue and success, so I think it’s just right that we get credit for being a part of the foundation of the game, and also some glory for that as well. The G League experience is much closer to the experience of your average person. They have a dream and they are working doggedly to achieve that dream — a narrative that most people would identify with.”

The unionization movement has been “the backbone of American prosperity, and I feel really strongly about that,” said Aubry, who comes from “a family of people who were in unions. Solidarity is so important.”

He also comes from a family with roots in Sag Harbor. His grandfather built a house in the 1970s in Hillcrest Terrace, one of the village’s original African-American resort communities. Middle-class Black families began flocking in the 1930s to Sag Harbor, one of few vacation destinations in America where it was possible for them to buy or build homes mostly isolated from discriminatory real-estate practices. Hillcrest Terrace has since been mostly absorbed into the larger village identity, but the remaining historically Black communities still exist under the acronym SANS (“Sag Harbor Hills, Azurest, and Ninevah subdivisions”). They are facing massive challenges from out-of-town developers who have spent the last eight years or so aggressively scooping up real estate and knocking down modest midcentury houses, replacing them with outsized luxury mansions as rental or investment properties.

Aubry, who can sometimes be seen walking his shih tzu, Oliver, down Sag Harbor’s Main Street, visited his grandfather’s house every summer. It’s where he and his wife and three kids live today. “In my formative years, that was the house and this is the neighborhood that hold a lot of memories for me, and certainly my memories of him,” he said.

In his pro-basketball career he was a globetrotter, moving frequently to places like Mexico, Switzerland, Peru, Dominican Republic, and the Netherlands, a lived experience that “made coming home to a place like Sag Harbor that much better.”

It’s fair to say that Aubry himself is making Sag Harbor a better place. He is a coach and referee in the Sag Harbor Youth Hoop program, a parent-run league that since the 1980s has been raising generations of players on foundations of the game plus all the life skills that come with being part of a team. He credits Shelly Cottrell and Heidi Wilson, two Sag Harbor school teachers and longtime Youth Hoop coaches, with teaching him how to be a coach himself. Aubry’s wife, Erica Arnold, is also a key volunteer in the program, on the logistics side.

“It really brought me back to the heart of why I love the game so much. It is accessible to people,” Aubry said. “They do an incredible job of building basketball infrastructure here in Sag Harbor, and you’re starting to see some of the Sag Harbor Youth Hoop players who are now varsity players having a huge impact.” (Pierson High School’s boys varsity basketball team made it all the way to the regional New York State playoffs in the school year that just ended.)

“It’s great having him in the program because no one’s played basketball at a higher level than him in our community,” said John Cottrell, who was president of Sag Harbor Youth Hoop from 2017 to 2022. “He has made a huge contribution.”

As a player, Aubry considered himself to be the underdog type. The East Elmhurst, Queens, native loved stepping up to play against even bigger athletes. He was a tall kid, taller than everybody else, and when that was the case, “you were a center. But it was still a position I was drawn to and something I was talented at. The things I was really good at on the court — I was a good rebounder, a good shot-blocker, really physical and athletic around the rim — all that worked to my benefit in the position.”

These days, he said, a player’s height doesn’t matter as much as his or her skill. “And it’s important when you’re coaching young athletes to give them an opportunity to develop in a number of ways and not pigeonhole them into positions too early.”

The most successful players speak of basketball as a mental game as much as it is a physical game. “The two things go hand-in-hand,” Aubry said. “It really goes to your understanding of the game, the ability to get outside of yourself, but it also is about how dedicated you are to growing your skill set. I tell the kids that your basketball skills are like a plant. If you water the plant, you will grow and stretch. If you don’t, it dies. It’s a lesson in perseverance and discipline.”

It’s also a lesson in the power of dreams.

“We all watch TV and see someone like Lebron James or Steph Curry perform at those levels, knowing that’s a pretty far-reaching dream,” Aubry said. “Look, the dream is important. It drives us and gives us direction, and direction is usually the hard part. . . . It provides a lot of structure for kids to build their lives around. If they play in college, awesome, if they make it to the professional level, impressive. At the very least you’re walking away with tools for success.”

The sport “has helped me find myself throughout my life — my identity. It has been a driving force for me since I was 10 years old,” he said. “I’ve always found beauty in the ability of five players on the court to collectively set a goal and actively work toward that goal. It’s something that is sacred to me. Basketball was so good to me and gave me the life l have.”