For more than 30 summers in East Hampton, starting in 1936, girls from 3 or 4 all the way to 18 could be found in a studio property on Lily Pond Lane — out on the grass, capering, leaping, skipping, and reaching for the halcyon skies — as they learned the art of dance in a lineage that descended directly from Isadora Duncan, the legendary choreographer and pioneer of contemporary dance.

This was Anita Zahn’s Summer School of the Arts.

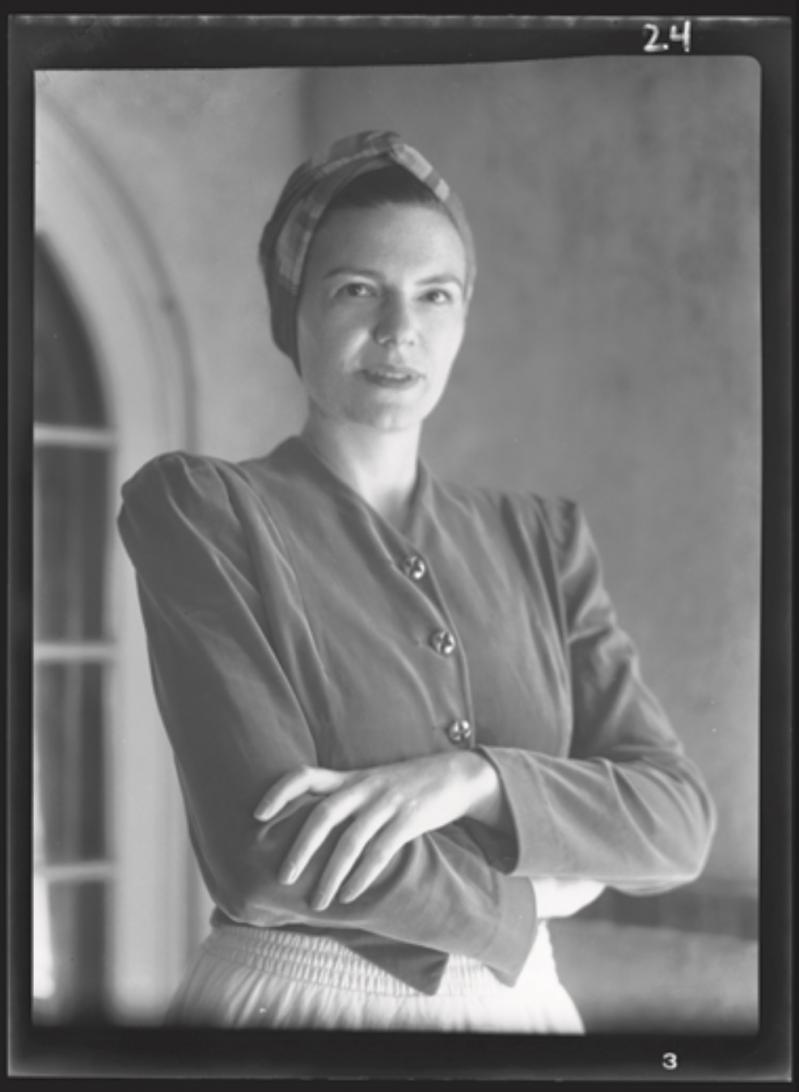

Zahn, born in 1904, had studied as a little girl with Isadora Duncan in Germany. She was among nine children who were brought out of Germany at the outbreak of World War I by Elizabeth Duncan, Isadora’s sister. They returned to Europe after the Great War, but when she was of age, Zahn came back to the States with an offer in hand to teach dance at the Children’s University School, now known as the Dalton School. In 1936, she brought her dance academy to Lily Pond Lane.

Zahn’s lessons in “Duncan dance” are still fondly remembered today by former East Hampton students.

“We had waltzes and polonaises and fabulous music and gorgeous dresses,” recalled Candy Osborne, who now lives in Tennessee. “We were dancing outside on the lawn and you could smell the privet blooming. It was idyllic.”

Zahn was “not strict,” Osborne said. “I had a riding teacher and she was strict. Anita was very graceful, and understanding that some of us were 3. . . . I loved it. I just loved it.”

Classes were Tuesdays through Fridays in the mornings in July and August. There would also be acting and poetry lessons, handcrafts, and breaks for juice and snacks, and “sometimes, if it was a nice day, my mom would load a few of the kids into her station wagon and we’d go swimming at Albert’s Landing,” said Osborne, whose family didn’t actually have enough money for the classes, so her mother worked for Zahn in exchange for tuition.

“We’d do a warmup and barre work, but we didn’t have a barre,” Osborne continued. “We had the edge of the wainscoting around the room and we put our feet up on there. I tried to be the first one in the room so I could be near the piano and put my foot up on it. Then I got too big to put my foot up on the piano.”

Duncan dance was more than just a formal technique, Zahn told The East Hampton Star in 1973, the year she sold her property on Lily Pond and began to wind down her years in East Hampton. Her girls practiced particular ways of “walking, running, skipping, and complexities thereof.” Dance was an elemental interchange with nature, the ebb and flow of tides, the rising and falling of Sun and Moon.

Duncan’s legacy still lives on in a sort of great-grandmotherly way, and Zahn danced a key role in that succession: The techniques were passed from Isadora Duncan to her sister, Elizabeth, to Zahn; and then from Zahn to Dicki Johnson Macy, who established a program called Rainbowdance in Boston in 1988. It’s still in operation today.

“Children experience collective joy, mirroring beautiful gestures that speak of affiliation and movements initiated from the physical and emotional heart,” Macy, also formerly of East Hampton, wrote in an academic paper titled Singing the Steps: Remembering Anita Zahn’s Duncan Pedagogy for Children in 2018.

Anita Zahn offered, through dance, an education in the “joy of relationship and harmony which comes from stillness and awareness,” Macy wrote.

Inseparable from Zahn’s teachings was masterful accompaniment on the piano by Mary Shambaugh, a composer and popular piano teacher with a house in Wainscott. “She wrote a waltz for me, Candy’s Waltz, but I can’t find anyone with a piano who can read music to play it for me,” Osborne said.

“Anita stood so beautifully. She moved so beautifully. . . . Apparently she was getting divorced, but none of her private life came into where she was teaching. We never got any kind of sadness — none of that ever showed. I never had any idea until I started looking things up,” Osborne said.

Joanne Lester O’Brien, another of Zahn’s students, remembers that her teacher “would tell us to feel the music, not just ‘flap our arms around.’ ”

“We wore pink leotards and pink skirts that Anita made for us. Mary played piano for all our classes,” O’Brien recalled. “I still remember a lot of the moves! Most of it was improvisational, but with a framework that she would give us.”

“As we got older, Anita was very direct in helping us with our changing bodies,” she continued. “She told us to talk with our mothers about using tampons, and shaving our armpits and legs, and using deodorant.”

In that 1973 interview with The Star, Zahn told Jack Graves — who’s been writing here, now, for more than 50 years, about as long as Zahn taught in New York City and East Hampton — that dancing with Isadora Duncan wasn’t just about dancing. “You came away saying ‘I saw a hurricane . . . a lake by the moon . . . a fallen child being resurrected.’ She got to you in such a human way.”

In comparing the Duncan method to ballet, Zahn told Graves that “it’s not as unnatural to the body as ballet. Ballet is very entertaining and marvelous. It was founded in Louis XIV’s time; it’s completely artificial; but it’s fine if you like to see people dancing on tiptoes and in tutus. Ballet is not American. Duncan dance grips you.”

Isadora Duncan died in 1927, Elizabeth Duncan in 1948. Anita Zahn died in 1994.

Macy wrote that Zahn had taught her students to “respect relationship and to strive, always, for harmony.”

“In swelling and withdrawing like the sea, in feeling the support of the wind’s force as we flew across the room, we acknowledged our connection with a greater life force,” she continued. “And yet, we also knew with Anita, that there was something beautiful and special about our individual differences. . . . In Anita’s mystical haven we learned that females had marvelous secrets which we would grow to know, by participating in life, not by rushing through it. . . . That one had to live each step, that we could not live life as a race whose tempo could be altered by jumping ahead or lingering too long at a time gone by.”