Abandoned house cats and their offspring adapt to life in the wild and take bloody vengeance on a small town. In short, that is the plot of a pulp terror novel set in Amagansett in the early 1970s. Two things about Berton Roueché’s Feral come as a surprise: Roueché was the most influential medical writer of the time, and the story had roots in one of his real-life neighbors (more on that later). Think of Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds, but with cats or, as a New York Times reviewer called it, “a feline Jaws.”

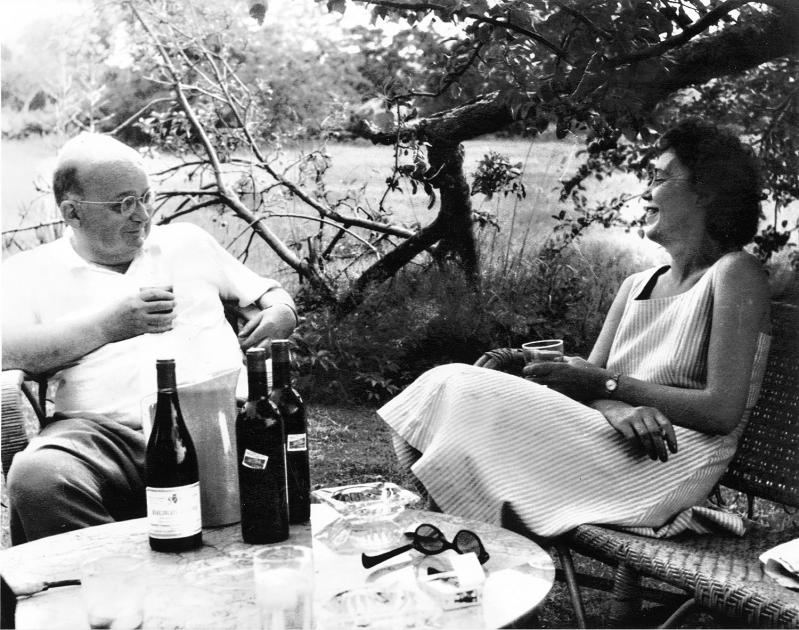

Roueché and his wife, Kay, came to live in Amagansett by way of a string of late 1940s summer rentals. In 1947 they took the T. Bernard Corrigan cottage on Apaquogue Road. Another summer they rented an old Parsons homestead in Springs with plans to make it their permanent home. That changed — Roueché would later say that Springs felt to him like suburbia — and they looked toward Amagansett. The lanes that ran off Main Street were perhaps too claustrophobic, but they found a setting to their liking in the woods outside Amagansett and bought a piece of rolling land, hired an architect, and commissioned a Modernist house tucked into a hillside. It was completed in 1958.

The Rouechés were almost insiders. Kay, a niece of Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, had been a member of the Ladies Village Improvement Society since 1952. Berton was one of the leaders of Guild Hall’s film club. Later on, as the pace of change increased on the South Fork, Kay and Berton helped establish the Stony Hill Association.

Roueché had been a staff writer at The New Yorker since roughly the end of World War II and was a well-known figure in the literary world of the city, noted especially for the medical mysteries published in the magazine under the heading Annals of Medicine. One of his New Yorker pieces was the basis of a film, Bigger Than Life, about a schoolteacher hopped up on cortisone whose life spirals into murderous psychosis. James Mason starred.

A standout among his early pieces at The New Yorker was The Case of the Eleven Blue Men, which appeared in the May 28, 1948, issue, initiating a new genre. Roueché’s first medical article at The New Yorker, it came to him by chance — a story about a group of men who turned up in several New York City hospitals on the same day with the peculiar commonality that each was blue. Eleven Blue Men described how city health officials determined the cause: a chance use of sodium nitrite in place of table salt in the morning oatmeal at the Eclipse Cafeteria on New York’s Bowery.

The Case of the Eleven Blue Men describes an early fall morning in New York City when a cop discovered a “ragged, aimless old man,” Roueché wrote, writhing in pain. There was nothing unusual about so-called Bowery bums in drunken states around Dey Street near the old Hudson Terminal, but when the cop got closer, he saw that the man’s nose, lips, and fingers were sky-blue. By midday, 10 more men, appearing in various shades of blue distress, ended up in downtown hospitals. The medical staffs were perplexed. Ultimately the trail led to a greasy-spoon diner where the cook, thinking he had reached into a salt tin on a shelf near the stove, had accidentally spiked a large batch of oatmeal with a handful of sodium nitrite. To make matters worse, a busboy had unintentionally topped up the salt shaker with yet more sodium nitrite. The investigators concluded that the men, heavy drinkers, craved salt, as some alcoholics do, and had each had in all probability used the same adulterated salt shaker, which tipped the toxic balance of each serving of oatmeal, causing the cyanosis.

The East Hampton Star’s publisher, Jeannette Edwards Rattray, was a fan of Roueché’s, making note each time something new arrived by mail. She was pleased by Roueché’s articles on trichinosis, typhoid, psittacosis, leprosy, smallpox, and tetanus that read like detective stories and were fascinating.

Early hints that something will go wrong in Roueché’s horror novel, Feral, come during a fictional New York couple’s first summer in Amagansett. Within the first dozen pages, Amy and Jack Bishop become the new owners of what Roueché called “the old Lester place” at “Quail Hill.” Amy quickly takes to country life, getting to know the locals, enjoying the fresh air. They give a young cat they adopt from a car mechanic the prosaic name Sneakers for its white feet.

Jack’s job as a science-magazine editor allows him to work from their new-to-them house. But at the end of the season it is time to get back to the city to be closer to his editor. Sneakers would not be happy in their apartment, they figure, so, as more than a few summer people did in those days, Amy and Jack agree they have to leave the kitty behind. They drop him near a house on a back lane then drive out of town.

The next summer, another ominous sign comes by way of a haggard stray dog that Jack and Amy find nearly immobile in the woods at the edge of their property. The beagle mix is heavily laden with ticks and has deep scratches, cuts perhaps, Jack notes, on its muzzle and belly. The town veterinarian, Dr. Tucker, agrees with Jack that the dog had come out on the losing end of a fight with a cat.

“Those cats, those strays — they’re not just wild. They’re crazy,” the vet says.

The woods at Stony Hill are full of cats, Dr. Tucker says, with more being born every day. It’s not the cats’ fault that they are sick and half-starved, he says. “I’m more inclined to blame the people who put them there. I mean the folks that come down for the summer and get a little kitten for the kids, and when it’s time to go back to the city, they just dump it off at the side of the road.”

The Bishops take in the dog and name it Sam. The reader gets the sense that Sam’s story will not end well.

More troubling events accumulate. Sets of threatening yellow eyes glint in a car’s headlights. There is a savagely ravaged dead opossum. The owners of a horse stable up the road from the Bishop house haven’t seen a single rat anywhere near the barns since May. Hens start to go missing at Shine’s Chicken Farm. A scenic bird walk is planned, but there are no birds. Jack begins to suspect that the cats in the woods have learned to hunt in groups, like lions, and are reverting to a wild state, attacking anything that moves. The town dog warden announces that cats are not in his job description.

Fall comes and, one night in bed, Amy notices a distant disturbing noise, wailing. “It sounds like cats,” she says. “A lot of cats.”

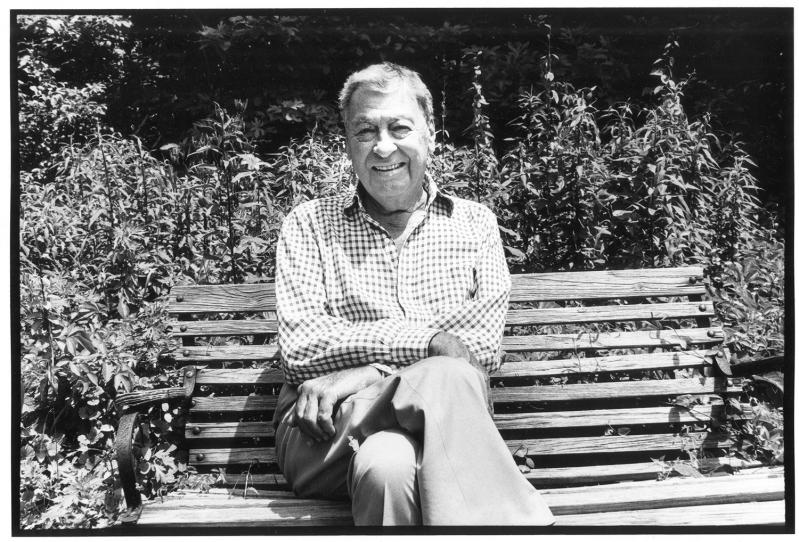

Roueché almost certainly never set out in life to write a horror novel about cats. He grew up in St. Louis. His high school yearbook photo, class of 1924, reveals a slightly amused young man with sharply arched, quizzical eyebrows and just a shadow of a smile at one corner of his mouth. He has thick, dark hair of the kind that would resist waving in the breeze as he walked. As a young man just graduated with a journalism degree from the University of Missouri, Roueché found a job as a reporter for The Kansas City Star. William Shawn, the editor of The New Yorker, hired him as a staff writer in 1944 after noticing Roueché’s articles in the St. Louis papers.

As his career progressed at The New Yorker, Berton and Kay divided their time between the city and Amagansett, fitting more and more into the East End community in each passing year. Roueché seemed to know everyone in and around East Hampton; he described a bad case of poison ivy suffered by Eunice Telfer Juckett, a teacher from East Hampton, in his article on that particular ailment, Leaves of Three. The Amagansett I.G.A. sold apples from Kay and Berton’s trees in late summer.

Well before 1974, when Harper and Row released Feral, Amagansett and the rest of the South Fork had come under massive development pressure. Roueché’s activism with the Stony Hill Association led to an appointment to the town planning board at a time when large subdivisions were clogging the agenda.

By 1970, fault lines in the community were deepening. Roueché, who had irritated the developers more than once, was not asked back for a second term. Another board member, Fred Yardley, resigned in protest. He was followed quickly by another, Frank Dayton. Yardley explained that Berton was “very conservation-minded and meticulous, perhaps to the point where he frustrated those who wanted to hurry things along.”

“Someone should care about East Hampton,” Yardley told a Star reporter after he quit. “Berton does . . . I do.”

The Rouechés were practically old-timers in 1967 when new neighbors, Peter and Deborah Light Perry, bought Hilly Close, the solemnly named domain of Samuel Rubin, the founder of Fabergé Perfumes. Hilly Close was a 30-acre estate otherwise known locally as Quail Hill and popular in winter among Amagansett kids for its sledding. The Perrys promptly changed the name back to Quail Hill. Alfred Scheffer, a Modernist East End architect, had designed Rubin’s main house around the centerpiece of a large beech tree in the living room, but it was the property’s windmill guest house that won Deborah’s heart.

Early on in Feral, Roueché makes a subtle dig at Rubin’s pretensions: “Quail Hill,” Amy said. “Oh, I think that is lovely. Is that the name of the house, too? I love it when a house has a name.”

“Well, no,” the real estate man, Mr. Lester, replies. “We don’t have much of that down here, Mrs. Bishop. A few of the summer people maybe — some of the big houses over on the ocean. No, this place they usually just call it the Lester place.”

Elsewhere in the book, Roueché seems to take a poke at the naturalist and writer Peter Matthiessen, who spent time working on the water and later documented Amagansett’s commercial-fishing culture in Men’s Lives. “I haven’t seen old Tony for a long time,” one of the figures in Feral says. “Is he still running around trying to be a Bonacker?”

“Harder than ever,” another says. “It’s got so now that he hardly ever speaks to anybody other than a bayman.”

As a place name, Quail Hill was an archaic bit of local geography. In a 1892 Star article, it was described as a place for church youth group outings with “Indian” bonfires. Whatever the conjunction of Stony Hill Road, Town Lane, and the Amagansett-Springs Road was called, as of the late 1960s, the Perrys were living there full time, raising their little boy, Michael, constructing a workshop. And taking in cats. Lots of cats.

Deborah Ann Light is remembered as a visionary benefactor who created the Quail Hill we know today and preserved the agrarian views of Amagansett for future generations with a donation of 220 acres to the Peconic Land Trust. She also, at one point, owned as many as 36 cats at Quail Hill.

At feeding time, dozens of cans of food were opened by four electric can-openers; Purina Cat Chow was bought by the pallet. The food was served in at least four long galvanized troughs of the sort used at a chicken farm, placed around the periphery of the kitchen and mud room. The cats were kept away until the food had been dropped into the troughs, then the doors were open and the mewling mass of fur rushed in. The sharp-eyed Roueché could hardly have missed their presence from his and Kay’s perch in their house with pumpkin-orange countertops less than a mile away.

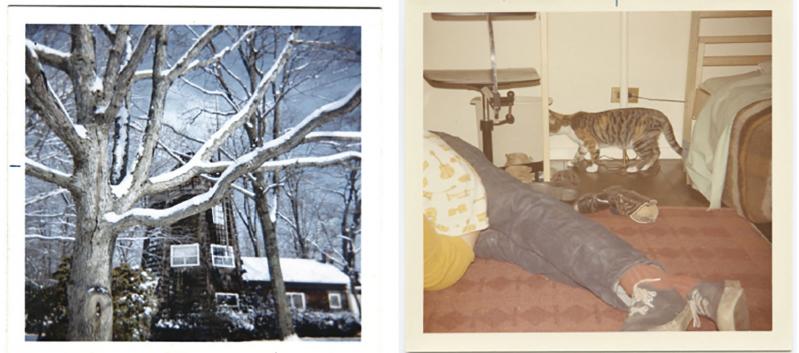

The Rouechés’ house at Stony Hill was designed by Robert Rosenberg to mimic the long, sloping roof lines of Long Island potato barns, right down to banked earth against the exterior walls to block the wind. Inside there were soaring ceilings, pine-board walls, and exposed beams. Roueché’s study was drawn up to minimize distractions, with white walls, a single window set too high to see out of, and a moss-green easy chair (as described in The New York Times Magazine). A desk, simply a top across cabinets, was painted black. On the study walls were paintings and exhibition posters by Jackson Pollock, Lee Krasner, Jane Freilicher, Jimmy Ernst, James Brooks, and Claus Hoie, most reflecting Roueché’s personal connection to them. A 1963 pen-and-ink drawing, a fanciful play on the letter “E,” was inscribed to him by Saul Steinberg. His records reflected his boyhood days in Kansas City, where jazz was played at school dances and in clubs, coming up the river from New Orleans. His collection included Kid Ory, Honoré Dutrey, King Oliver, and Jelly Roll Morton.

Roueché’s gift as a medical storyteller comes to the surface in Feral in a fine-grained description of septicemia from a cat bite. The victim offers a few table scraps to a stray, moves to touch its head, and receives a puncture to the bone of one hand. By night, the wound is throbbing and swollen. A tetanus shot and some antibiotics offer little relief. A terrible headache comes next. At last, as red streaks run the length of her arm, a surgeon orders her to a hospital, her thumb at risk of amputation.

More: A boy intent on noodling with a girl in a romantic spot in the woods is savagely attacked. Jack and Amy find their dog dead of horrible scratch wounds. Before long, the cats kill a town cop in the Bishops’ driveway. A fatal sweep ensues with armed men combing the woods. The cats are cornered at a creek and a brutal slaughter follows.

Cat problem solved. Or is it? On a moonlit night, Jack hears an outside garbage can crash to the ground. “It wasn’t the wind,” he thinks. “It couldn’t be the wind.” He turns and runs.

As with just about the slightest stirring of a leaf here in East Hampton, Feral touched off a skirmish on The Star’s Letters to the Editor pages. The first blast came from a writer who objected to Roueché’s description of cats turned super-vicious: “Thus he can justify the sickening scenes of violence and slaughter. He builds the horror skillfully, playing on the standard fears and prejudices of cat-haters, and by the end of the book any non-animal lover will certainly be more disposed to solve the animal population explosion with a gun than to approach the problem with intelligence and compassion.”

Jean Stafford, a famous writer herself and friend of the Rouechés, was having none of it. In her counter-letter to the editor, after describing a scene in which one of her own cats happily settled on Berton’s lap, she let loose on the critics. The attackers did not know what fiction was and were “talking hysterically through their big wormy old black hats,” she wrote. “The villains in Feral are not the cats. They are the humanoid brutes who forsake the pets who have amused them during the summer season.”

Another correspondent in support of Roueché commented on the surprisingly passionate nature of the reaction to Feral. “As I have observed on the letters page before,” Alvin Detwiller wrote, “your readers get a great deal more worked up over dogs and cats than they do over the problems of human beings.”

(The more things change . . . )

Another commentator sent a letter to the editor that said, “Anyone who could be so viciously destructive as to even imagine that cats are capable of such cruelty as devouring a policeman, should be burned alive at the stake and I’d be happy to light the first match.”

Some weeks later, an arch-sarcastic Star columnist declared Feral to be “a thinly described political tract” in which “the policeman stands in for the Establishment” and “the cats represent all those subversive radicals who are trying to undermine our system by overthrowing its symbols.” And if that weren’t enough, “Some critics have seen the cats as representing the hard-pressed middle-class taxpayers who finally revolt against the increasing demands of a swollen bureaucracy and rise up in holy wrath and eat their masters.” It was 1975, after all, even in East Hampton.

For his part, the editor in a column about birds reported, “Mr. Roueché also wanted me to know that he had seen five bluebirds at his bird bath at once recently, and that he would be most pleased to see more letters protesting his novel Feral. They help sales.”

Roueché continued to publish, writing widely on the environment, on disappearing America, on nature, and on medical matters. His depiction of the times was acute. In a piece in The New Yorker in 1978 about a case in which dozens of schoolchildren fell suddenly ill, he describes how collective obsessional behavior among the human species takes many forms: “These range in social seriousness from the transient tyranny of the fad (skateboards, Farrah Fawcett-Majors, jogging, Perrier with a twist) and the eager lockstep of fashion (blue jeans, hoopskirts, stomping boots, white kid gloves, the beard, the wig) to the delirium of the My Lai massacre and the frenzy of the race riot and the witch hunt.” The man could turn a phrase. In all, Roueché spent 50 years at The New Yorker and published 20 books.

As he got older, his health deteriorated. He had emphysema and was depressed, Kay told the police after he killed himself, at the age of 84, with a shotgun while seated in a lawn chair at the Stony Hill house in 1994. Fittingly, perhaps, for a man who had devoted much of his professional career to medical writing, the incident was described in detail in The Star.

An appreciation in The New England Journal of Medicine some 10 years after his death said Roueché’s writings “introduced not only laypersons but also future generations of physicians to the art of medicine.” At Dartmouth School of Medicine, a course called “Medical Detectives” was based on Roueché’s work.

A final mystery involving Roueché was unearthed (literally) in 2011 when a landscaper digging a trench for an irrigation line found a World War II hand grenade on Berton and Kay’s property at Stony Hill. The county bomb squad came and detonated it just in case. No one ever came forward to explain how it might have gotten there.