Northwest Woods, The, Definition: Broad area of woodlands situated northwest of the Village of East Hampton, on the west side of Three Mile Harbor and running up to Northwest Harbor and to the boundary of the Village of Sag Harbor. Northwest and the Northwest Woods are essentially coterminous, although the latter term is more commonly applied to the woods lying in Alewife Brook Neck. This would exclude the lands lying west of the East Hampton-Sag Harbor Turnpike (New York State Route 114). In its broadest application, the phrase “Northwest Woods” encompasses some 10,000 acres of woodland — or nearly one-quarter of East Hampton’s land mass.

The Northwest Woods has the second highest ground elevations in the town, higher than those at Miller’s Ground, Stony Hill, and Montauk’s Shagwanac Hills, but lower than in Hither Woods. The highest elevation in Northwest Woods is 182 feet above mean sea level, southeast of Whooping Hollow Road and not far from Cosdrew Lane. Most of Northwest is either part of the Ronkonkoma moraine or part of one or more recessional moraines. As such, its soils tend to be sandy, acidic, and poor in nutrients.

The Northwest Woods have always been, to some degree, East Hampton’s wilderness. They were sparsely settled between 1757 and the 1880s, as a community of scattered farmsteads, but no roads in Northwest were paved before the 1930s and significant residential use of the area did not occur until modern real estate development commenced on the west side of Three Mile Harbor in the late 1940s and the 1950s. For most of East Hampton’s history, the Northwest Woods have been simply a source of timber, firewood, and game animals.

The south-central portion of Northwest Woods contains extensive stands of pitch pines and, especially, white pine. This is not the case farther north. The largely undisturbed forest in Cedar Point County Park, for example, is a classic oak-hickory deciduous mix.

When Northwest Was a Village

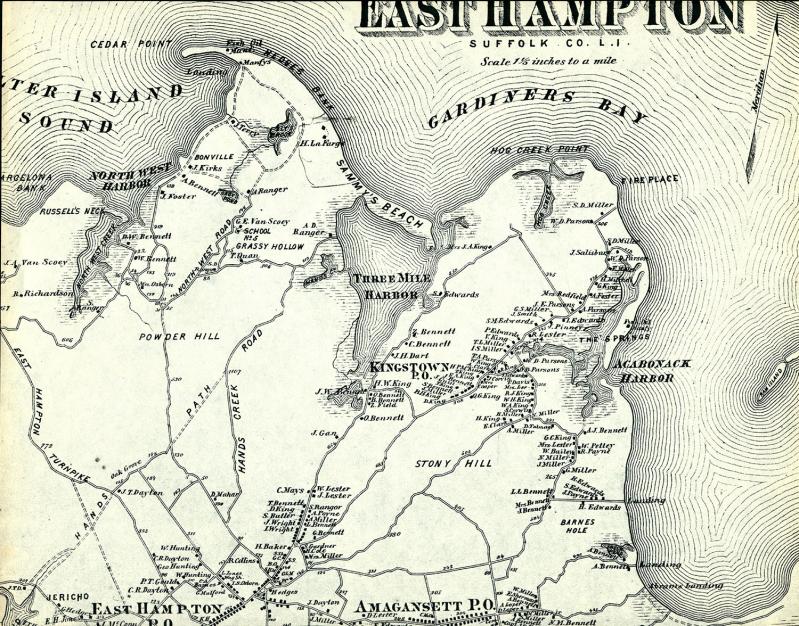

In 1873, F. W. Beers, Comstock, and Cline published an Atlas of Long Island. It showed all of East Hampton, except Montauk, in very respectable detail. The 1873 Beers Atlas, as it is commonly called, provides a snapshot of “old Northwest” in its post–Civil War heyday. It was a placid community of a few homes and farmsteads, scattered throughout thousands of acres of woods. The Terry, Van Scoy, and Ranger farms — backbone of Northwest — were still going strong. Josiah Kirk was about to begin his self-immolatory battle with the town trustees.

At Barcelona Neck, still called Russell’s Neck on the Beers map, J. Austin Van Scoy occupied David Russell’s onetime farm. Stephen Ranger had a house at Pine Swamp. A couple of Bennetts had houses at or near Northwest Landing. A Mrs. Osborn lived at what would be Ella Lan Bennett’s on Northwest Landing Road.

Farther north, someone identified as J. Foster lived at the old Phoebe Van Scoy farm (which would become John Monks’s place) and Josiah Kirk was settled in on his large farm on Northwest Harbor, bracing himself for his long fight with the town trustees over the rights to take seaweed off “his” beach. The Terry farm to Kirk’s north was owned by Jeremiah Terry. George E. Van Scoy had a home on the Van Scoy farm off Northwest Road. This had been the first true settlement in Northwest Woods, hewn out of the forest by Isaac Van Scoy and his wife, Mercy, beginning in 1757. Sylvester D. Ranger in 1873 lived on the Ranger farm on Northwest Road that to later generations would be known as the Peach Farm. The fish-oil business had led to the construction of an “oil works” on Cedar Beach. Henry La Farge lived by the landing that would

later bear his name. Tryphena Quaw, a Black or possibly Native-American woman, lived by herself in a hollow not far from

Hand’s Creek to which she, too, would lend her name.

Yet, in hardly more than a decade from the publication of the Beers map, all this would change — and quickly. For “old Northwest,” the decline would be abrupt. In 1886, the Van Scoy farm, progenitor of all the other Northwest farmsteads, was sold to Sineus C. M. Talmage of Georgica. In 1885, the Northwest School District would end its operations. That same year, the Terry farm was sold to Henry Wells of Greenport. And Josiah Kirk, having won his lawsuit against the trustees but spent all his money in doing so, would be forced to sell his farm to Edward Driscoll. Over a period of several months in the fall of 1885, all of the now-unoccupied buildings on Driscoll’s new holdings — including the “hill house” occupied by Annie Bennett in 1873 — would be burned to the ground by arsonists.

In late September of 1892, William Wallace Tooker, that indefatigable historian of Long Island’s Indian history, visited and photographed the Van Scoy farm. Several of his photographs have survived. They are poignant. The two-story Van Scoy homestead, its lines still plumb straight after 121 years, stands windowless. The great Northwest oak shades the home’s southern face. It was in this house that Isaac Van Scoy pitchforked three British soldiers who came to rob him one night. Planks are missing from the gable end on the west side of the house, and the addition on its easterly end has detached from the main building and is slowly tumbling to the ground. The farmland around the homestead is still mostly open, and a large barn stands a couple hundred feet from the house. But the fence lines are all in disrepair. The whole scene is one of incipient ruin.

The shuttering of Northwest School, the sale of the Terry farm, and the sale and then destruction of Kirk’s farm — all occurring in or about 1885 — closed a chapter of East Hampton’s history. In a few more years, with the Long Island Rail

Road extended to East Hampton, the town’s economy would be increasingly focused on tourism and the resort trade. For East Hampton’s farmers — and there were still many at that time — the coming of the railroad meant agriculture could

move from subsistence farming to real commercial farming, with the railroad available to export crops.

An Early Attempt to Preserve Northwest Woods

By 1923, Northwest Woods was virtually a wilderness. The old farmsteads had been abandoned and were reverting to

woodland. There were only a scattered few homes in the entire district. The only habitations at that time in all of Northwest were two or three homes on Barcelona Neck (Little Northwest), one or two houses at the end of Northwest Landing Road, Monks’s place near the end of Mile Hill Road, the Peach Farm on Northwest Road, and a caretaker’s house for the hunting preserve at Cedar Point. There were a dozen or so houses or summer shanties on the west side of Three Mile Harbor. These were scattered about from Turtle Back (south of Springy Banks) northward. The majority of these houses were off what is now Three Mile Harbor Drive, between Hand’s Creek and Sammy’s Beach.

In 1923, in the broad interior of Northwest Woods, the Peach Farm excepted, there was absolutely nothing — not a single dwelling place except, perhaps, a hermit’s shack here or there. A sense of what Northwest was like at the time can be found in a June 1923 article in The East Hampton Star. A foolish argument at Sag Harbor’s watchcase factory led to murder: One worker smashed another’s head with an iron cuspidor. Police and local sheriffs tracked the assailant into Northwest, which The Star described in almost breathless terms as the “Great Northwest woods, a tract of primeval forest stretching for ten miles between Sag Harbor and East Hampton.” The perpetrator, incidentally, was found and arrested at Monks’s place — one of the few locations in Northwest where he could have found shelter.

If one turned out from Sag Harbor Turnpike at, say, Stephen Hand’s Path and headed north — or started up Hand’s Creek Road from Cedar Street — one entered a vast forest of thousands of acres, with not a single paved road to be found. Maybe East Hampton people of the time should be forgiven for thinking it would always stay that way. But there were a handful who realized change was coming, and it was best to be out in front of it.

Thus it was that Town Supervisor Kenneth E. Davis, a Republican, offered a proposition to be placed on the November ballot in 1923, for the town to raise the sum of $20,000 in each of the years 1923 and 1924 (a total of $40,000) to buy land

in the Northwest Woods, at a price not to exceed $20 an acre. The targeted area was to be bounded by the waters of Three Mile Harbor, Gardiner’s Bay, Northwest Harbor, and Northwest Creek, and to lie north of a line from Hardscrabble to the New Ground area near Oakview Highway. It was estimated that the money raised could preserve about 2,000 acres

of land in Northwest Woods. Supervisor Davis suggested that the land so acquired could be turned over to the town trustees, to be managed in perpetuity as public forest land.

This was a far-seeing proposal for the 1920s, considering how little land East Hampton Town has actually purchased in Northwest Woods since then. In the interior of Northwest, Supervisor Davis’s proposal, if adopted, would have provided East Hampton with its own wilderness park right in its backyard. Certainly, much more of Northwest Woods would still be woods today if this proposal had passed. Unfortunately, although Supervisor Davis was easily re-elected on Election Day, Nov. 7, 1923, East Hampton’s voters turned down Proposition No. 3 by a lopsided vote of 432 to 119. There is no evidence that any sort of coordinated effort at favorable publicity, such as would happen today, was attempted. If the electorate had questions, they apparently went unanswered. Even The East Hampton Star, later an advocate for land preservation, editorialized against the passage of Proposition No. 3. Supervisor Davis’s grand idea was dead.

After 1923, the town’s electorate was not asked again to vote on any proposals to spend money for land preservation — not until 1970. By then, the issue of rural character and open-space preservation was front and center in South Fork politics. And since 1970, when a $600,000 bond issue to buy wetlands and other open space was approved by the voters, no proposition to spend public money to preserve land has ever been defeated in East Hampton Town (excepting East Hampton Village).

Forest Fires and Other Natural Threats

Forest fires occasionally scorched Northwest Woods. In olden times, there was no way of stopping or controlling such fires. In the 20th century, it became much more practical to fight forest fires. Volunteer fire departments bought “brush trucks” and water tankers and the general availability of public water hydrants, or even fire wells and cisterns installed at subdivisions where public water is not available, gave firefighters a secure water supply. Before the 1980s, however, really large fires were not all that infrequent.

Large woods fires were most common in the spring months, especially April and May. The biggest infernos would make local and regional newspapers. The Sag Harbor Corrector, for example, wrote of a forest fire in November 1874 that burned several hundred acres of woods near Two Holes of Water. In April 1884, a large fire burned from near Monks’s place and the future Grace Estate to the south and east. According to The Sag Harbor Express, the effects of the fire were felt from Powder Hill on the west to the Grassy Hollow area on the east, and the line of advancing fire was a mile-and-a-half long. A forest fire at the beginning of April 1900, a month of fires throughout East Hampton Town, burned from Grassy Hollow almost to Freetown, requiring over a hundred volunteers to quench the blaze. Thousands of acres of valuable woods were said to have been destroyed.

In May 1911 The Corrector reported on a great forest fire at Northwest, burning hundreds of acres of timber near Ely Brook, all the way to Hedges Banks and the shore of Three Mile Harbor. Another big fire began near Hardscrabble on July 6, 1913, and burned for three days in a northerly and easterly direction. It scorched hundreds of acres of woods. An even bigger fire apparently occurred on May 13 and 14, 1916. The East Hampton Star called it “the largest fire that has ever occurred in this vicinity,” and said it destroyed 3,000 to 4,000 acres of woods between the Sag Harbor Turnpike and Three Mile Harbor Road. Like most major woods fires in East Hampton history, this fire occurred in springtime.

The gradual development of Northwest Woods with housing subdivisions has significantly reduced the risk of major forest fires. The last notable fire in Northwest, in the early 1980s, burned over an area southeast of Northwest Road which would be subdivided soon afterward as the Cordwood Hollow and Blueberry Knolls subdivisions. Some years afterward, this writer and friends spotted what appeared to be a large fire, flying sparks and all, during a winter night’s full-moon hike in Barcelona Neck. The fire could be seen across Northwest Harbor, in the vicinity of the Grace Estate. We did not have cellphones at that time, and by the time we hiked out of Barcelona, drove to the fire zone, and alerted a neighbor in the Lighthouse Landing subdivision, more than an hour had passed. Yet the fire, located in the Grace Estate subdivision before any houses had been built there, was largely restricted to the ground cover and had really not taken hold in the tree canopy.

Today, it is hard for a woods fire in Northwest Woods to get rolling before being discovered by motorists or homeowners,

and the many new houses, driveways, and subdivision roads act as fire breaks to slow down or halt a fire’s advance. There can be other forms of natural damage besides fire. Gypsy-moth infestations used to break out from time to time, destroying leaves on the woods in all areas of the town, including sections of Northwest. More recently, parts of North-

west Woods, especially along Swamp Road and Sag Harbor Turnpike and westward into the Wainscott School District, have been very badly affected by an infestation of southern pine beetles that began in 2017. The southern pine beetle was first discovered on Long Island by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation in late 2014, in the Central Pine Barrens. The beetles had reached Northwest Woods by 2017. The insect primarily attacks pitch pines; tens of thousands of pitch pines have been killed in Northwest in recent years.

The most insidious form of vegetative damage, though, is probably overbrowsing of the understory by deer. As the local population of white-tailed deer has grown and grown, so too has the damage caused by their overfeeding. In some parts of the Grace Estate, for example, young saplings almost never reach maturity; they are eaten first by the deer. This overbrowsing of native tree and plant species denudes the forest floor of vegetation and, in some places, has encouraged the widespread growth of less edible invasive plants such as Japanese barberry.

Land Preservation

The wide sweep of Northwest Harbor today presents a beautiful tableau of protected natural lands. From north to south on the East Hampton side of Northwest Harbor are the 596-acre Cedar Point County Park, then south of Alewife Brook Landing the Lighthouse Landing and Grace Estate subdivisions, the 516-acre Grace Estate Preserve with the 17-acre Whelan Preserve attached, then the Settlement at Northwest subdivision, and finally Northwest Harbor County Park (some 337 acres) and New York State’s Barcelona Neck Preserve (about 338 acres). On the Shelter Island side of Northwest

Harbor is the Nature Conservancy’s crown jewel, the Mashomack Preserve, which the Conservancy tabulates at 2,350 acres in size. These parklands dominate the shore of Northwest Harbor.

Barcelona Neck and its immediately surrounding state-owned lands (including the Little Northwest Creek wetlands) consist of about 526 acres. All told, there were approximately 965 acres of contiguous protected open space centered on Barcelona Neck in 2023. This includes all the preserved land around Barcelona Neck which lies east of Sag Harbor Turnpike and north or west of Swamp Road. As of last year, East Hampton Town and Suffolk County owned about 96 acres of parkland south of Barcelona and Northwest Creek, and the town owned an additional four or five acres on the south side of Northwest Landing Road adjoining Northwest Harbor County Park.

It is fortunate that the state and county put so much money into the acquisition of parkland at Northwest because the town, with the notable exception of the Grace Estate, has not spent a very large amount of money to buy open space in Northwest Woods. Proportionately much greater efforts at land preservation have been made almost everywhere else in the town, including Springs. This is especially true in the interior areas of Northwest Woods, where most of the preserved land consists of subdivision reserved areas, for which the town paid nothing. The town also obtained two fairly large tracts of land from Suffolk County in 1948 as a result of tax defaults. Those are the 52.1-acre main parcel in the Edwards Hole Preserve (between Sag Harbor Turnpike and Two Holes of Water Road) and the 56.4-acre Winthrop Gardiner or Camp Norwesca Town Park, on Old House Landing Road.

The town has acquired, either by condemnation or negotiated purchase since 1976, about 64 acres around Chatfield’s Hole, off Two Holes of Water Road. The town also cooperated with Suffolk County in purchasing 84 acres on Three Mile

Harbor Road just south of Hand’s Creek — the former Boys and Girls Harbor property. Much of the 96 acres of preserved land just south of Barcelona Neck (especially the former Alden Talbird property, the Staudinger’s Pond Preserve, and the

Helena Curtis Preserve) is owned by the town — some of it acquired with the help of Suffolk County. But a good deal of the

town-owned land in Northwest’s interior is the product of subdivisions. Among the most important of the subdivisions which

created reserved areas in Northwest Woods are Northwest Estates, Grassy Hollow Estates, Blueberry Knolls, Cordwood Hollow, Hand’s Creek Hollow, White Pine Knolls, and White Tail Knolls. This is not a comprehensive list, but each of the

subdivisions just mentioned has one or more important public trails running through its reserved area today.

The first significant modern recreational trail in Northwest Woods, and the town’s first “greenbelt” trail — meaning a trail that passes through and links multiple different parcels of preserved open space — was the Northwest Path. The Northwest Path was conceived by this writer during the fall of 1987, which was about two years after the town had

acquired the Grace Estate. With town board permission, the trail was cleared and opened by the East Hampton Trails

Preservation Society in the fall and winter of 1988 and 1989. The Northwest Path runs from the northeast side of Sag Harbor Turnpike northward to and into Cedar Point County Park. The pathway did, and still does, traverse the town-owned

Edwards Hole Preserve, Chatfield’s Hole Preserve, and Grace Estate Preserve, as well as Cedar Point County Park. It also utilizes a short section of trail easement over private land just south of Bull Path, runs through a 2.6-acre lot on the north side of Bull Path which the town purchased from Jon Conran, through the White Pine Knolls subdivision reserved

area, and — finally — through the 45-acre Wilson’s Grove Preserve which Marillyn Wilson donated to Peconic Land Trust in 2008. In 1988 Marillyn Wilson, acting upon a request by this writer, very graciously consented to the Northwest Path being put through her land (and within sight of her house).

The Northwest Path was inaugurated with a hike on Feb. 12, 1989. Forty-five hikers participated. The Northwest Path set the template for most of the trails that have since been created in East Hampton Town by the trails preservation society. Those trails include another greenbelt trail in Northwest Woods called the Debra Foster Path, named for longtime Planning Board member and chair (and, later, Town Councilwoman) Debra Foster. The Debra Foster Path, which was opened in 1995, runs from Two Holes of Water Road (next to Chatfield’s Hole) to Northwest Road near the Northwest Schoolhouse site.

Today most of the Northwest Path and a significant part of the Debra Foster Path are segments in the Paumanok Path, a

magnifient 125-mile route from Montauk Point all the way to Rocky Point in western Suffolk, and a walk through nature on the Paumanok is also a walk through history. The fact that we have preserved these ancient rights of way for future generations is testament to the power of a determined citizenry.