Like life anywhere, life on the East End comes with certain built-in fears and anxieties. Blood-sucking, disease-infested ticks might top your list of creeping fears, but we also have hair-raising road conditions, a lack of primary-care doctors when we need one, rip tides, the occasional Portuguese man-o-war jellyfish, great white sharks, and the Montauk Monster. North Sea residents, last month, were treated to the unsettling news that investigators were searching the area for human remains allegedly connected to the accused Gilgo Beach serial killer. We’re here to add another frightening tale of a possible — potentially? maybe? — serial killer to your bad dreams.

This story dates back to the very earliest days of Bridgehampton. We gleaned what follows from later newspaper articles as well as historical documents. It is the story of a Bridgehampton gentleman of some means who, during his lifetime, was, seemingly, a fairly normal, honorable citizen, but who, after his death, was remembered as a killer, monster, and sadist. This is the story of John Wick Esq.

An author named George Howell wrote about Wick in an 1887 book called The Early History of Southampton, Long Island, N.Y. Howell refers to Wick as a “surge maker,” or weaver of wool goods, who was born around 1661 in Southold and began his career in Southampton Village. Wick apparently acquired considerable wealth, and, at some point, left Southampton for Bridgehampton, where he bought land at what is today the northwest corner of Main Street and the roads leading north to Sag Harbor and Noyac.

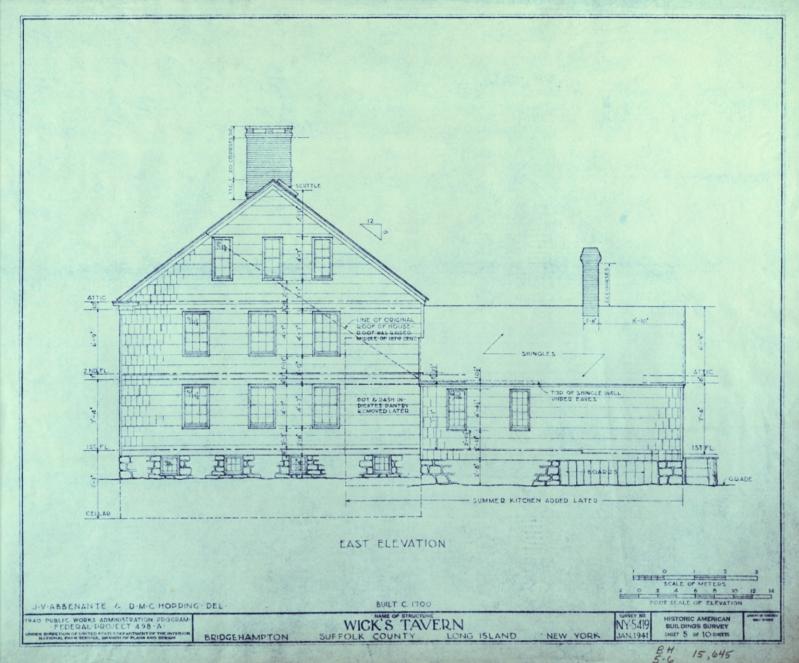

Around 1689, John Wick and his ironically named wife, Temperance, built Wick’s Tavern, a well-known stopping point at this crossroads that later became known as the Bull’s Head, for the sign of a bull that hung from a tree out front. (More recently, the public has called the white Greek Revival mansion on the opposite corner “the Bull’s Head,” after an inn and restaurant that went in and out of business over the last few decades of the 20th century, but that building was constructed in 1843 and is more properly known as the Rose House, today the Topping Rose.)

John Wick as a tavern keeper was canny, for sure. Wick’s was the only roadside inn or tavern in the area, providing rum, beer, and lodging for weary travelers. Wick was enterprising, too. According to William D. Halsey, in Sketches From Local History (1935), it was Wick who partnered in 1712 with another merchant, Edward Howell, to clear the woods to create Merchants Path as a route for merchandise (whale oil, tallow, hides, timber, and, of course, rum by the barrel) arriving by ship at Northwest Harbor to be carted by oxen to the southerly villages. Historical records tell us that Wick also opened the first brewery on the East End, located at the head of the “Sagaponack swamp.” Before long, Wick had been honored with various public offices, including trustee and magistrate.

But who would a Hamptons real estate speculator be without a bit of scandal attached to his name? An entry in the “Calendar of State Papers” dated January 1699 and held in the British National Archives tells us that Wick was accused of collusion with a privateer by the name of Josiah Raynor, a colleague of the infamous pirate Captain Thomas Tew (also known as “the Rhode Island pirate”). There was some business of Raynor holding a chest of treasure confiscated by the sheriff, but all was forgiven and forgotten when the booty was returned along with a bribe of 50 pounds — called a “present” — from Wick to Gov. Benjamin Fletcher. The governor promoted John Wick to be sheriff for all of Suffolk for the year 1699-1700.

In the winter of 1718, Wick was 58 years old, and dying. He made out a will on Dec. 15 stipulating that his favorite son, John, be provided with a good education — indeed, John Wick went on to graduate from Yale — and about a month later, he departed this world for the next.

Wick left Temperance the use of half their house, one half of his cellar, and a third of his other real estate.

It was after his death that neighbors and travelers began to talk of him not as a respectable citizen and honorable magistrate, but as evil incarnate. According to Early History, the frigid January night when Wick died, villagers fishing offshore witnessed a glowing object in the sky, moving like a fireball out to sea, and remarked, “There goes the devil, dragging John Wick’s soul down to hell.”

In death, Wick’s reputation was so bad, according to James Truslow Adams’s Old Memorials of Bridgehampton (1914), that neighbors said he possessed supernatural powers and practiced dark magic. It was reputed that traveling peddlers hosted by Wick at the inn would check in for the night and never be seen or heard from again — murdered for their meager possessions and buried underneath the tavern. And, like many if not most people of any means on the East End — and in New York as a whole — Wick was an enslaver. One heinous story, told in Old Memorials, recounts how Wick ordered an elderly enslaved man to dig a well. When the laborer failed to find water, Wick supposedly removed the ladder and buried the man alive.

Alleged supernatural occurrences piled up around his memory. One story, recounted in The Star in 1975, says that grave diggers couldn’t bury him in the consecrated ground of the church cemetery, because masses of ants kept swarming the grave as they dropped in each shovel of earth. This supposedly was why Wick’s coffin was moved to his own property (in a location that, according to the records, would put it underneath the Hampton Library).

Wick’s descendants, unhappy with the dispensation of his will, performed a seance invoking his spirit to amend it in court, according to Early History. It is unknown if the magical ritual achieved its purpose; there is no record of a spectral John Wick appearing in court.

One of Wick’s sons auctioned off the property. Although a crowd gathered, townsfolk were hesitant to bid, fearing the land was cursed. Captain Edward Topping came upon the gathering while riding on horseback and jokingly exclaimed “a penny more” just as the auction ended and, being the only bidder, acquired all of the property for a penny. Topping found it impossible to sell any parcel of it onward, and so he sold his own farm and moved into a house on the western end of Wick’s stretch of Main Street plots.

Wick’s Tavern would pass through many hands. It survived the British occupation during the American Revolution and withstood the War of 1812. It served rum and ale to Union volunteers during the Civil War. It hosted gatherings during World War I, too. Yet, during World War II, for reasons hard to understand today, the people of Bridgehampton agreed that it should be leveled and replaced with a Shell gas station. That gas station was replaced with a beverage store that was in use into the 1990s, then once again leveled as if nothing good could stay on that spot. Today the pristine, white N.Y.U. Langone Medical Associates building stands there . . . because even a fiend wants redemption, right?