SALLY RICHARDSON

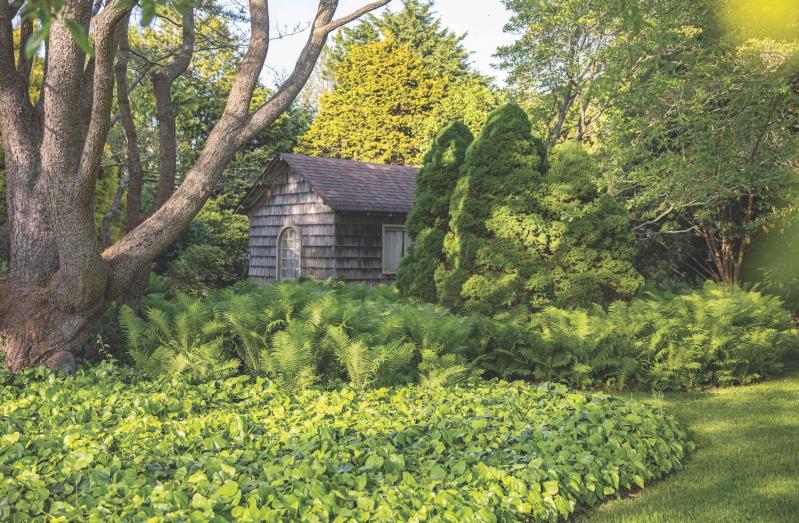

Sally Richardson’s Montauk property has a studio where she makes the art that she sells to everybody else and a much smaller shed where she makes art for herself.

The shed is tiny, 6 feet by 10 feet. It’s a mini-studio surrounded by a 20-foot belt of trees, vegetable beds, and perennial flowers — somewhat akin to the greenspaces and sheds of the East Anglian village of Wivenhoe, up a river estuary from the east coast of England, where Richardson grew up, she says.

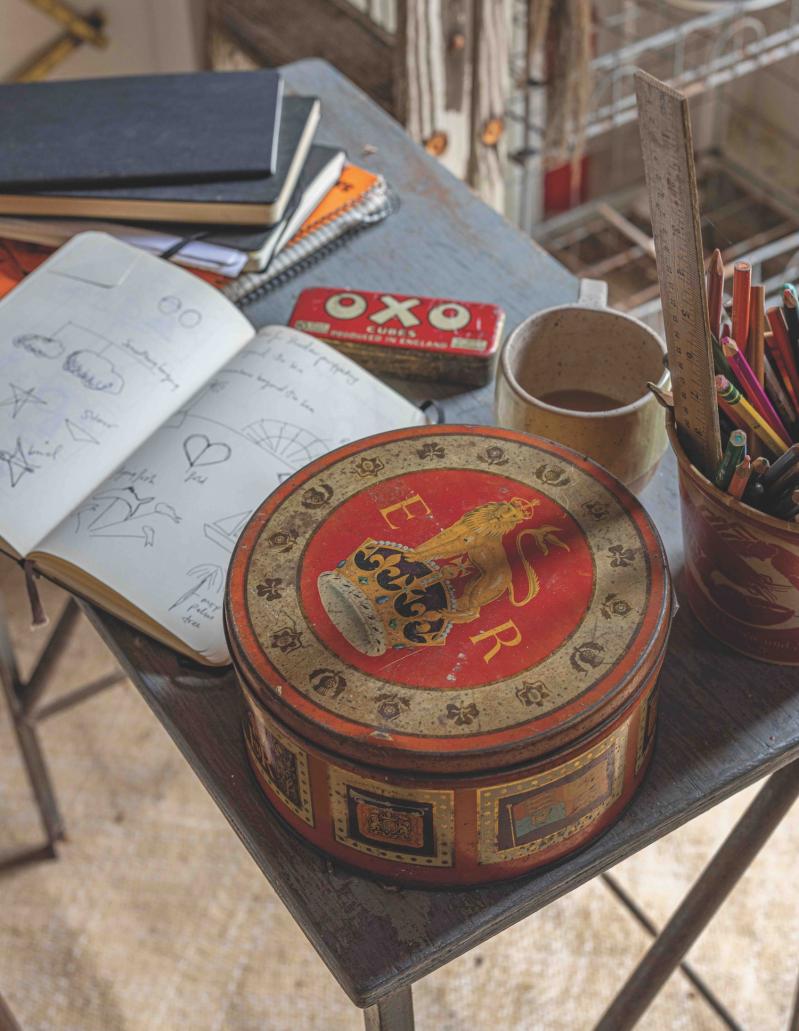

A sculptor of wood and stone, she uses the shed for doing “whimsical work.”

“These are sculptures that are made from found objects, assemblage pieces, which is different to the way I normally work,” Richardson says. “I do collages using papier-mâché and sometimes they’re doodles or sketches that I’ve done over the years. And I kind of make them into these 3-D totem sort of sculptures, so they tend to be a bit more autobiographical.”

Sometimes Richardson makes her shed art of plastic: straws, bottle caps, and bottles that she finds on the beach. “I definitely have a serious issue with single-use plastic,” she says.

The shed, like the art that comes from it, is strictly for her.

“It’s a small, little space that just brings so much joy. You don’t really need a huge, vast space to get pleasure out of. It’s tiny, and I would just say every time I go there every morning, it just brings a lot of joy to my life, because I have to walk through the garden, which is joyful in itself. In addition to the art, it’s also a way to observe nature really close up, which is thrilling for the seasons and how as one perennial is fading, another one is coming into bloom. That’s always exciting, to see what’s blooming next.”

SABINA STREETER

Sabina Streeter looks into the yard of her Sag Harbor home and sees a little Bavaria. A contemporary painter and portraitist, she was raised in Munich and still has a home in the Alps, a humble structure where the family used to make schnapps, converted by her brother into a tiny house. She loves the warm, stripped-bare but functional cluster of small buildings — four old sheds — on her property in Sag Harbor, in part, because amid the modern structures of her neighborhood they remind her of the past. She and her daughter, Lilly Streeter, a jewelry designer, use the sheds as their own private artists’ colony in summertime.

“What’s so nice is the bucolic character of it,” Streeter says, “but now I have a developer with a spec house next door with a pool. I’m staying put, but if I would sell it today, a developer would buy it and rip it all apart.”

Other than the addition of new electrical wiring and roofs, the four sheds, which include a former horse barn and chicken coop, are as historically preserved as Streeter can make them. Like her father, the architect Rudolph Thoennessen, Streeter is an ardent preservationist. The Field family of Sag Harbor built the sheds and main house in 1885, creating what feels today like a miniature village green, and Streeter keeps them as they always were, to the point of not heating them. This reduces their utility as workplaces from April to Thanksgiving Day, but Streeter doesn’t mind. Even the windows are still original.

“There’s not that much left in America,” Streeter says, “and if you tear every 18th and 19th century building down and modernize it, then you have nothing left.”

MARILEE FOSTER

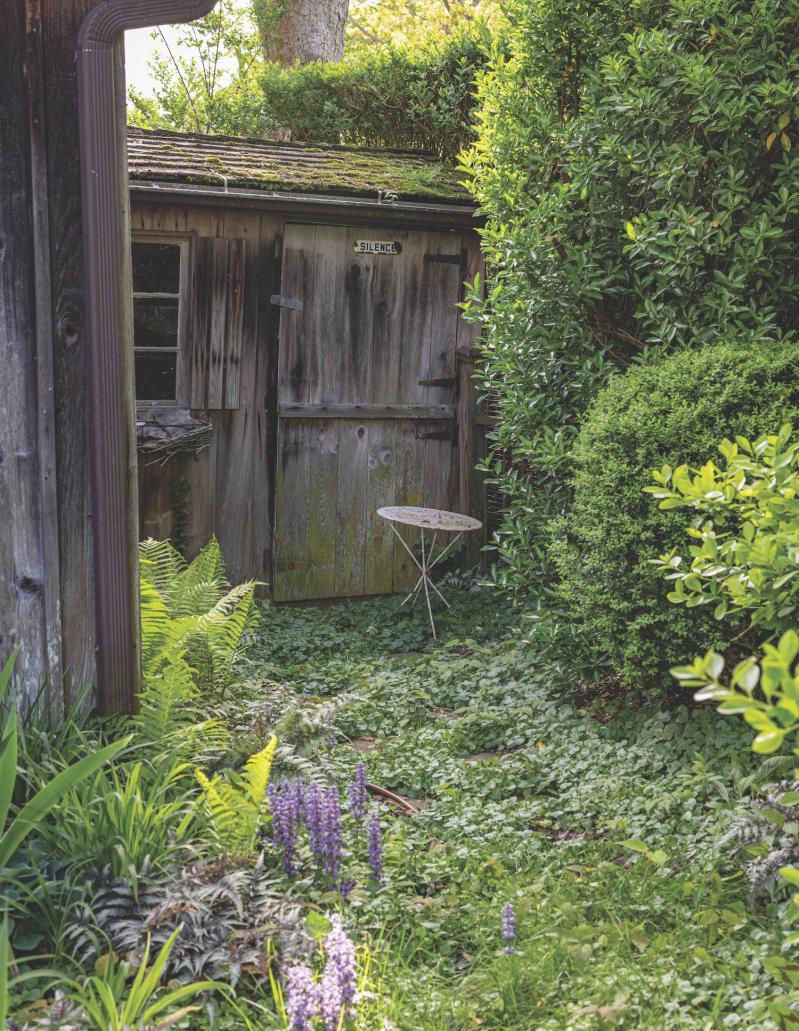

Historically speaking, the most interesting of the seven sheds on the Foster family’s 250-acre Sagaponack Potato Company farm in Sagaponack usually gets mistaken for an outhouse, though Marilee Foster doesn’t quite understand why.

More than 200 years old, the modest shed in question was originally part of what was called a “weight house,” to which farmers from miles around brought their produce. Entire trucks or wagons would roll up onto an eight-by-10-foot platform in front to have their loads weighed. The scale mechanism is still inside. Parts resemble an old doctor’s office scale with sliding weights that were moved out along a three-foot bronze, grooved balance bar, she says.

“It’s like a truly unique shed that I don’t think anyone else has,” Foster says. “It used to have a massive scale that was in a pit that was in front of it.”

Customers who come to the farm, on Sagg Main Street, to buy vegetables, potatoes, honey, beans, and other seasonal items, often make assumptions. “People ask us to use the bathroom all the time because they assume it’s not too much bigger than a bathroom stall, really, but it is not a bath- room,” she says, adding the obvious: “It has a window in it, and clearly they wouldn’t have put windows in outhouses.”

Like most working farms, this one has several sheds and outbuildings used for different purposes, for storage or for chickens. People often want to sneak around in them, she says, but not the old weight house. “People aren’t really curious about that kind of thing,” she says. “The birds and wrens build nests in there because it’s just kind of a quiet little shed that nobody goes in.”

Foster can’t see ever tearing down any of the farm’s sheds.

“No, no. Never, never never,” she says. “because they’re cool. It’s like they have parents. There’s little stories about them.”

JILL MUSNICKI

Jill Musnicki sees Sag Harbor transforming itself all around her in ways she doesn’t like. Old, traditional houses that stood for generations are being sold at enormously high prices, then razed and replaced by newer structures. Old trees that stood for generations are chopped down, too, to be replaced by lavish landscaping. But the human displacement, of course, is worse. Young families cannot afford to live in our corner of Long Island, and older families continue to age and, often with age, cannot afford to remain in houses they raised families in.

That’s why the 57-year-old painter, photographer, and gardener counts herself fortunate every time she finds herself entering the former greenhouse that she uses as a studio.

Grandfathered under local zoning laws, it is among three sheds that came with her tiny, 1,200-square-foot-home, which she occupies with her husband and daughter. The sheds give the property a versatility and utility that couldn’t be replaced or replicated — or permitted — today. The house has an unusual history. It began existence as an Army barracks at Camp Upton during World War I, and was bought, disassembled, as a kit by an Italian family that reassembled it in Sag Harbor in the 1930s. That’s the family Musnicki and her husband, Jamison Ellis, bought the property from.

“I’m always feeling grateful that we have this place, that we got it so long ago when we could afford it,” Musnicki says. “I don’t think we could ever, you know — today with all the prices the way they are — it just doesn’t seem like we would ever live here. I grew up in Bridgehampton, but always, when I walk into my property, I just always feel grateful, having the extra space with such a small house.”

SARAH KOENIG

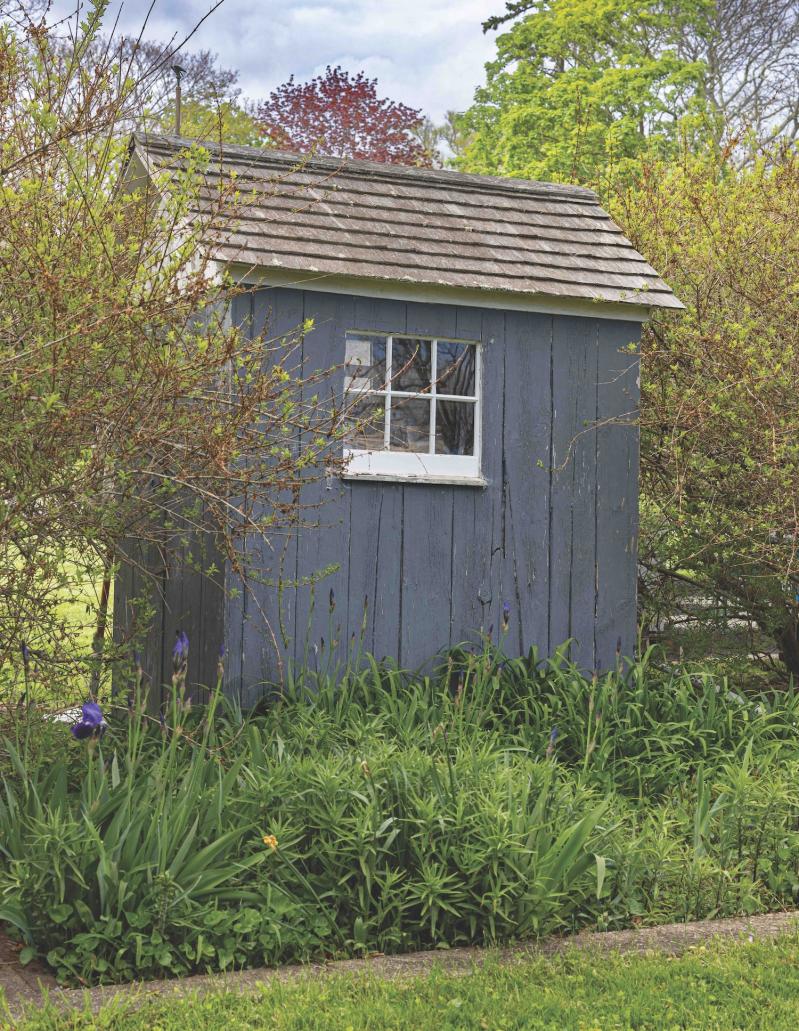

She doesn’t use it for writing anymore, but some of the biggest successes of Sarah Koenig’s career emanated from within a tiny, fairly ramshackle shed in the garden behind her house on Madison Street in Sag Harbor. It’s where the podcast pioneer and producer-slash-reporter wrote the first two seasons of Serial, the Peabody-winning nonfiction series.

Koenig thinks she got the idea for disappearing into a garden shed, to work, from her stepfather, the late author Peter Matthiessen, who wrote several of his celebrated books in a (much larger and more substantial) shed office in a corner of the family property off Bridge Lane in Sagaponack.

Putting the work shed together around 15 years ago was a chore — but a happy chore. She stapled straw beach matting to the floor (“the kind you get in a roll from the hardware store”) and painted the interior gray with a cream trim. She put a curtain on the “sweet window” and added a flower box. Her kids helped: “I remember them naked and covered in paint, very small kids with paint brushes, very cute,” she says. “I have fond memories of working in there and feeling, like, ‘Look at me! I created a space where I can think and get work done!’ ”

She loved it while it lasted. A few good seasons.

“Honestly, it was never that good a shed. It was too little and claustrophobic. And hot,” Koenig says. “It’s fallen into disuse mostly because the internet never really worked that well out there, which was always a challenge. For meetings, I’d have to go back into the house anyway. Plus, as the kids got older, needing a really private workspace wasn’t so much an issue. Once the kids weren’t so small and annoying anymore,” she says, laughing, “I could work more easily in the house.”

Now the shed is in “total disrepair,” says the South Fork native, who splits her time these days between Sag Harbor, Baltimore, and State College, Pennsylvania. It won’t be used again for writing again any time soon — if ever. “It began to really fall apart. The neighbor put in privet, of course, with a sprinkler system, and one of the sprinklers was wonky and sprayed water straight against the side of the shed for about a year, rotting one whole side. I kept patching it up with crazy boards, but then the raccoons were doing disgusting things on the roof, and now it’s a horror show and needs to be torn down.”