No one knew how long Jimmy Taber Jr. had been overboard. He’d slipped out of the Captain Kidd’s wheelhouse to smoke a joint. He knew his father, the captain of the lobster boat at the helm, disapproved of pot smoking, so young Taber didn’t say a word as he stepped out on the deck. None of the three other people on board, including Taber’s best friend, Frank Ganley, who was helping that day, noticed his absence.

Out on the deck, leaning against a gunwale, Taber lost his balance in the rolling seas and slipped. In the water miles from shore, he watched in terror as the Captain Kidd steamed away. He yelled for help, but there was no way anyone could hear him in the wheelhouse over the sound of the engines. His waders filled with water and began dragging him under, so he struggled but successfully removed them.

Jimmy Taber knew he couldn’t last in that freezing 45-degree water. He probably had an hour or two before hypothermia would kill him. His only hope would be that someone on the boat would notice his absence and the vessel would turn back to look for him. But the boat plowed away toward the horizon.

The Captain Kidd, a working lobster boat out of Three Mile Harbor, had been out off Eastern Plains Point for most of that morning, a cold, cloudy, windy day. Its captain, James Taber Sr., and three mates — Jimmy Taber, Ganley, and Lex McClosky — were pulling all Taber’s pots for the season. It was Dec. 21 and the last run of 1988 before winter set in hard.

Trouble finds Frank Ganley. Not that he doesn’t find it. He’ll be the first to admit he’s no saint. But real trouble, life or death trouble, that’s the kind of trouble that has been part of life since he was a kid. “I’ve seen too many people die,” he said this spring. “I learned young, life is so valuable. It’s gone in a second; one minute you’re here talking to someone, the next thing they’re gone.”

At the age of 10 Ganley was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma, cancer of the lymph nodes. “I had cancer everywhere but my brain. They gave me six months to live,” he said.

He credits the closeness of the East Hampton community for saving his life. Friends, and friends of friends, were his saviors. “If it wasn’t for the people who come out here from the city, summer friends, I would never have connected with the doctor who saved my life, Dr. Ira Halperin,” he says.

Ganley’s dad, Frank J. Ganley, would take his son to New York every week for chemotherapy treatments. Frank senior had an East Hampton landscaping business and he wanted more out of it. He would stop on the way in or on the way home to take landscape design and horticulture classes at Farmingdale State College and little Frank, his body fighting back the cancer inside him, would wait.

...

“Suddenly someone asked, ‘Where’s Jimmy?’” I don’t know how long it had been since Jimmy was gone when we real- ized he’d gone outside,” Ganley recalls.

Ganley and McClosky went out to look around.

“It hit me right away. Jimmy was gone. He could be dead.”

Jimmy Taber and Frank Ganley had been inseparable since before grade school in Springs. Now he’d gone over- board miles from shore in the middle of the winter in Gardiner’s Bay. For how long? Ten minutes? Longer? No one knew. The captain turned the boat around, and without the benefit of 21st-century navigation systems, began retracing their journey, following the boat’s wake. Ganley scrambled on top of the wheelhouse to search the horizon.

The Captain Kidd steamed for what seemed like miles with Frank on lookout, until he screamed out: He could see Taber floating with his arms out, his red hair just above the surface of the water. By the time the boat pulled up to where they’d spotted him, he had gone under.

Ganley plunged into the water.

“I’d kept my eye on the spot and I figured I would dive down and find him,” Ganley said. “I never felt the cold, not a thing. I dove down and just kept diving and looking and then I saw a flash of red or something. It was his hair, because all I remember is that I had his hair in my hands. I pulled him up by his hair.”

Taber was unconscious.

“I was pretty sure he was dead.”

By the time the two men got pulled onto the Captain Kidd, both men had hypothermia. Taber was out and wasn’t breathing.

Ganley wasn’t supposed to be there that day. He had just flown home, almost on a whim, from Milan where he had been working as a rising fashion model for the Wilhelmina agency. He had been working for the Italian brand Best Company — and “partying, and going to clubs with the beautiful people in Italy,” he said.

But it was Christmas, and he missed home, so he grabbed a flight to New York and got himself to Springs. Ganley’s mother was so surprised and unprepared when he showed up that he ended up heading over to Jimmy’s house, where he spent the night. That evening Taber told him he and his dad would be pulling pots the next day. Ganley should come, he said. They roused in the dark the next day and headed over to Wolfie’s (now Springs Tavern, previously the famous Jungle Pete’s) and had a few crack-o-dawn drinks, although Ganley himself didn’t partake.

“That’s the way it was back then, a lot of drinking.”

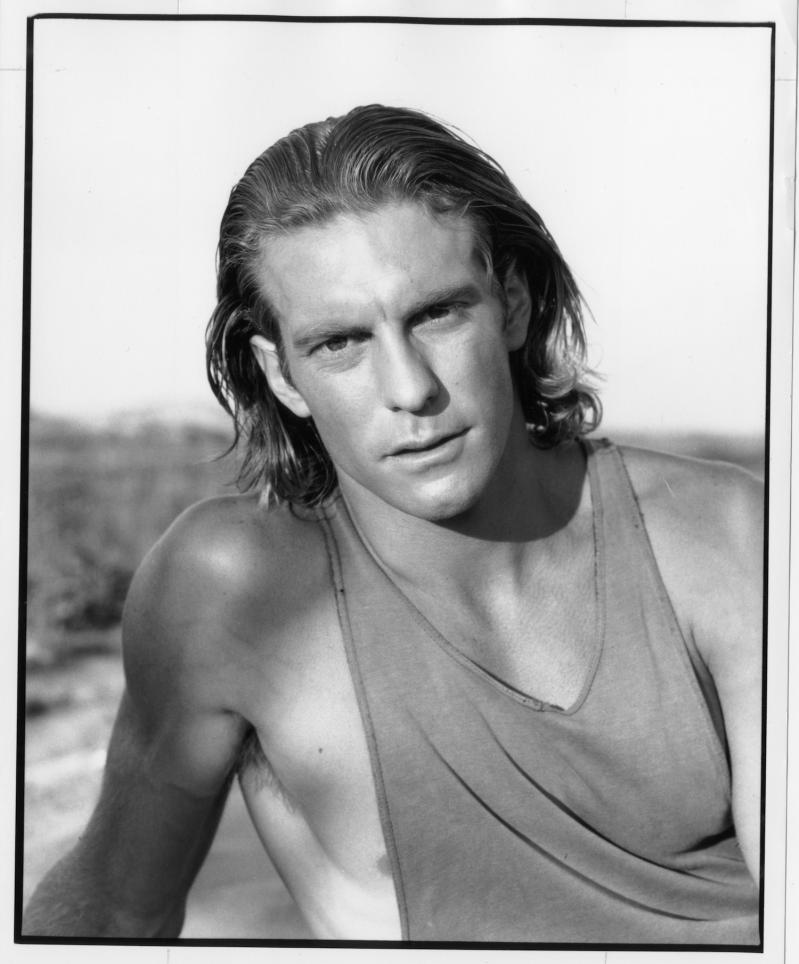

Frank Ganley was a striking 20-something, with a chiseled physique and long, blond hair. Had he succeeded as an actor — he tried and abandoned the idea after failing to memorize the lines at an audition — his looks and muscles qualified him for a role as Tarzan. His modeling story is an emblematic East Hampton tale, a dizzying and dazzling convergence of two worlds.

Ganley’s mom owned and ran a successful garden center on Fort Pond Boulevard, the Round Hearth, and through customer friends she got Frank a job as a prop helper on an Estée Lauder shoot. The producers and photographers took one look at Terry Ganley’s son and pulled him into the shoot itself alongside a striking, young Ford model. Willow Bay was the daughter of a New York City magazine and media executive, a Phillips Andover and University of Pennsylvania graduate who would go on to have a huge modeling career before becoming a well-known journalist and media personality, an anchor at ABC and CNN, and a journalism-school dean. Ganley was a proud Bonacker who grew up kicking around the neighborhoods at the mouth of Three Mile Harbor and “barely made it out of high school.”

“One of those Estée Lauder shoots with Willow was at a house over near the Maidstone, for their sun stuff. We were in and out of a pool, in bathing suits all day. I remember it was kind of cold. But who’s complaining? I was working with Willow Bay, I got to stare at this beautiful girl for eight hours all day and walk away with $1,500.”

Around the same time he’d caught the eye of another Round Hearth customer, the photographer and former Ford model Betsy Cameron. Cameron began taking pictures of Ganley, helping him build his portfolio and using the photographs herself for posters that would become iconic. Ganley was picked up by Wilhelmina and began working in the city.

It was the beginning of a wild ride.

“I remember walking into the Lobster Roll, a bunch of my friends were sitting there having lunch, and I come in arm in arm with Willow,” Ganley recalled. “I was just this little kid and there I was with a superstar.”

...

The radio distress calls from the Captain Kidd mustered three responses. A Coast Guard vessel out of Montauk began steaming to the scene, and the Coast Guard Air Station in Brooklyn (which no longer exists) dispatched a helicopter. A Sea Tow captain out of Greenport, Joe Frohnhoefer, and his mate, Don Garside, were first on the scene.

By the time Frohnhoefer got there, Jimmy Taber was lying stiff on the floor of the wheelhouse. Ganley and McClosky had given their friend mouth to mouth and cut off his soaked, cold clothes to cover him with whatever dry items they had, but hypothermia had set in and would not let up.

“I couldn’t get a pulse when I first got to him,” Frohnhoefer told The East Hampton Star the next day. “Muscle rigidity had set in. His body was so stiff I couldn’t get his eyelids open.”

Within a few minutes, the Coast Guard chopper was overhead and lowering a man down onto the Captain Kidd on a cable. But in the wind and rolling seas the maneuver went awry and a Coast Guard swimmer named Walter Prim landed with a crash in the middle of a towering stack of James Taber’s waterlogged and rotting wooden lobster pots.

“It took a few minutes for him to get out from all those lines and busted pots,” Ganley recalled.

Prim assessed both men, each of whom were in deadly stages of hypothermia. An airlift off the deck of the boat would be too risky, he decided, and the Kidd was ordered to the docks in Three Mile Harbor where the chopper could safely collect them and fly them to the hospital.

...

Ganley was 16 when he was told his cancer was in remission. He had been in and out of treatment for six years. The following year, his father died. He was 48, felled by spreading melanoma.

“It destroyed me,” the younger Ganley said. “My dream was to live next to my dad, work with him, join the fire department, and never leave East Hampton.

“I watched this 180-pound man whittle down to 100 pounds and disappear. ...One day I walked into the house on Bruce Lane and he was dead.”

...

All the town’s emergency services had heard the radio chatter about the vessel in distress on Gardiner’s Bay. It seemed to Ganley that every volunteer and friend he knew from the fire departments and ambulance crews in Springs and East Hampton had shown up to meet the Captain Kidd.

Amid all that, the chopper landed and the two men were airlifted to Eastern Long Island Hospital in Greenport where they were treated for hypothermia. Ganley recovered quickly and was released that evening but Taber was in bad shape and remained at the hospital for several days.

The weeks that followed were a blur of thank-yous, accolades, and partying.

“I was kind of freaked out and I was kind of this big hero. Fishermen don’t always survive these kinds of things,”

Ganley said. “We never paid for a drink anywhere. We were like rock stars every- where we went.” But something had shifted for him. He kept modeling and doing a little work in the landscape trade, but it felt like something was missing from his life. He began to drink too much, he recalls. The modeling work was coming in bits and pieces, but it was inconsistent. The next step on the modeling-career ladder would be acting. But he flubbed the audition and abandoned the idea.

Then the I.R.S. tracked him down for unpaid taxes for much of his modeling and other work and he hit a fork in the road. On a visit to friends in Florida in 1991, he decided to move to Boca Raton and become a lifeguard. The steady work was a savior but over the years he’s come to realize that it is the job itself, helping and saving people, that called to him. He’s been standing watch and pulling distressed and drowning people from the surf since 1992.

...

Diane Pohanka had just been broad- sided on her bicycle by a man driving a Chevy Silverado truck. The bones in both her legs were broken, including her right femur.

It was August 2023, and she was sprawled on the scalding-hot pavement on Highway A1A, the coastal road in Boca Raton. She was in agonizing pain and unable to move. Cars and trucks kept driving by. No one was stopping to help.

“I was trying to understand why nobody was coming for me,” weeks after the incident Pohanka told The Coastal Star newspaper. “I couldn’t move. I didn’t know if I was dying.”

Boca Raton Ocean Rescue Lieutenant Frank Ganley was getting gas for one of the emergency vehicles when he spotted Pohanka on the ground. He flipped on his emergency lights, drove up the shoul- der, and dropped to her side. He checked her vitals and made sure an ambulance was on the way. Then he simply offered the comfort of his presence and his hand.

“I knew she had some serious injuries. But there was nothing I could do, so I just held her hand,” he said. “She was scared, I could tell, scared that she was going to die.”

Pohanka recalls : “He was my lifeline, my angel.”

When the ambulance crew arrived, she wouldn’t let go. “Who wants to be alone at a time like that?” said Ganley, who regretted having to let go of her hand and return to his day.

Some six weeks later, badly beaten up but walking with a cane, Pohanka hobbled into Ocean Rescue headquarters to give Ganley a hug.

At 59 — and turning 60 on July 23 of this year — Ganley finds himself asking more and more questions about life and death and the randomness of events that alter the course of our lives. He remembers reading the paper the day after his near-death experience on the Captain Kidd and noting that at about the same time his friend was drowning a terrorist bomb had exploded in a Pan Am flight over Scotland, killing 270 people on the plane and on the ground where the wreckage landed.

“What happened to us seems pretty minor,” he said.

But, he asks, what if he had not returned from Italy and not been on that boat? Or what if he had not been home in East Hampton for both his parents’ deaths ?

...

That day on Gardiner’s Bay with his friend Jimmy Taber guided Ganley into his life; it also haunts him. Jimmy and Ganley drifted apart over the years but were connected forever in some mysterious way. When Taber died in 2022, the news came as a shock. Taber, like Ganley, had moved to Florida, and Frank wanted to rekindle their friendship but it hadn’t happened.

But Ganley has thrived in Boca Raton. His 31 years as a lifeguard have included more rescues than he can count — and a four-year run as a winner in the most prestigious national competition of basic life support skills among emergency medical service teams.

He misses home. He returns to East Hampton twice a year to be with friends, the community he’s always known and loved. He’s still a full-fledged Bonacker, an honorary member of East Hampton Ocean Rescue, and, even more important for local bona fides, won the town’s annual Largest Clam Contest a few years ago.

When Ganley began talking about his life for this story, the first thing he described was the terrifying realization he had up on that wheelhouse scanning the horizon. It was a sort of awakening.

“We’re all on this journey. One moment you’re hanging out with your best friend, and the next he’s gone. It can all be over just like that. He was just gone.”

Writer’s note: The facts of this story are as they were described by Frank Ganley and from press accounts of the incident.