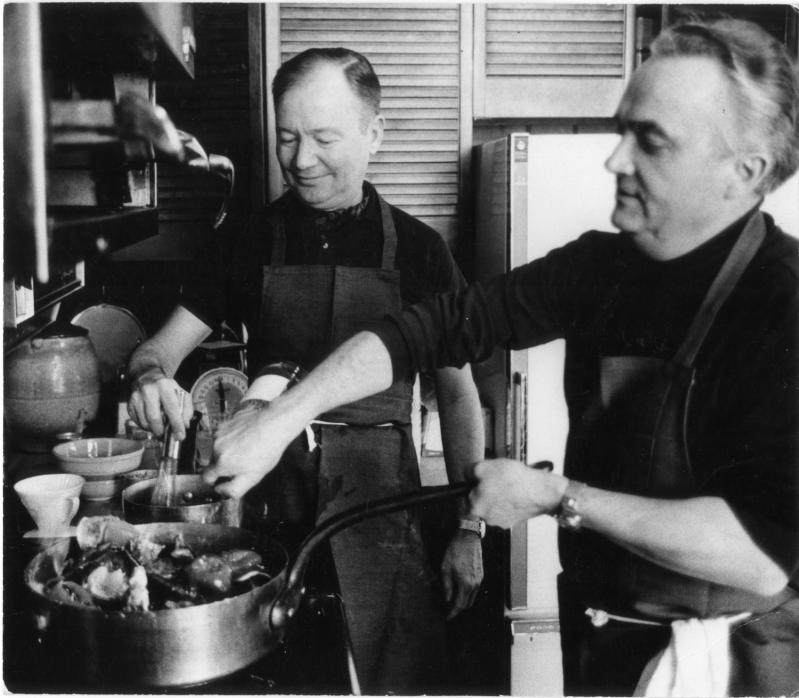

One winter Saturday in the 1970s, Pierre Franey and Craig Claiborne were giving a cooking demonstration before a packed audience in the John Drew Theater, as they often did to benefit Guild Hall, when an elderly woman, who happened to be sitting right in front of M. Franey’s wife and their three children, was overheard to ask her white-haired companion if she knew “whether those two were a ‘couple’? ”

Everett Rattray, then the editor of The East Hampton Star, who was sitting with Betty Franey and the children, reported that the pair “pursued the subject at length, to the vast amusement of the silent Franeys.”

“No,” he continued, writing in his weekly column, “they are just friends, fast friends, men who know more about food than anyone else in the nation and enjoy cooking together.”

Their friendship began in the 1950s, but was cemented in 1960, when Claiborne, The New York Times’s food critic, was striking fear into the hearts of restaurateurs with his newly invented four-star restaurant-rating system. One of Manhattan’s finest French restaurants, Le Pavillon, where Franey was employed as executive chef, had abruptly closed its doors, without notice or explanation, sending shock waves through its devoted coterie of ladies who lunched and its nightly celebrity clientele.

Claiborne, ever alert to kitchen gossip, learned that Henri Soulé, Le Pavillon’s owner — a noted tyrant — was embroiled in a dispute with his staff. Soulé, who also owned East Hampton’s Hedges Inn at the time, was refusing to pay overtime to his employees during the summer months, when the number of diners at 5 East 55th Street plummeted, and Franey insisted that without it his staff would be earning less than a living wage.

The restaurant critic sided with the chef, and his story of the standoff landed on the front page of The Times, an embarrassment from which Le Pavillon never fully recovered. Franey resigned, and years later Claiborne wrote that the episode was “the first planting of the seeds” of the pair’s long association, “without which my life would have been impoverished.”

By the time of that incident, the Franey family had been summering on Gardiner’s Bay in Springs for several years, with Claiborne as an occasional weekend guest. Soon after the story of Le Pavillon ran, he built a place of his own, on a piece of vacant land scouted out for him by Betty Franey. (He didn’t much like the developer’s name for the area — Clearwater Beach — and would tell people the house was “on King’s Point Road in Springs.”)

Over the years, the chef and the critic spent untold hours together in one or the other’s East End kitchen, experimenting with new dishes and cooking, often for quite large dinner parties. They shared ideas, recipes, restaurants, friends, and the food pages of The Times, almost always incorporating local seafood and promoting garden-fresh produce — a radical approach in an age of Spaghetti O’s and Swanson’s frozen TV dinners. They helped “raise food to its status as the dominant art form of the late 20th century,” gushed The Guardian newspaper, and they certainly helped to change the way Americans thought about food shopping.

And yet both loved rich, bad-for-you foods — “charcuteries, grilled pigs’ feet, grilled black and white sausages (boudins), preserved goose, thick peasant soups,” as Claiborne, who was born in Sunflower, Miss., wistfully recalled in his 1983 autobiography, A Feast Made for Laughter. (Four years before, he’d been diagnosed with high blood pressure and taken salt off his menu; also sugar, fats, and beef. He lost 20 pounds in a few months and got a cookbook out of it as well: Craig Claiborne’s Gourmet Diet.)

Val Heller, Joseph Heller’s widow, recalls that before his doctor put him on the low-salt diet, Claiborne frequented the Old Stove Pub (still going strong on Montauk Highway in Sagaponack) for its grilled chops and steaks. He could also be found on Friday nights sitting alone in a secluded corner of Casa Albona, an Amagansett stopover beloved of locals and weekenders on their way east, dining on fish that had been swimming hours before.

Both men’s Springs kitchens were fitted out with all manner of cookery appliances. Franey’s, which was smaller, contained, among other exotics, a duck press, which they used to make canard à la presse. Claiborne’s kitchen, which he’d had built on to his modest A-frame house, was enormous.

That house stood high on a bluff overlooking Gardiner’s Bay, and it was the pair’s habit, while experimenting with recipes, to toss bits and pieces of unneeded meats or vegetables over the side of the bluff into the water. One spring, in 1976, working on a veal recipe for a book, they ordered four calves’ heads, weighing about 50 pounds apiece, from a wholesale distributor in New Jersey.

When the order arrived, they were horrified. Unlike veal from meat dealers in the city, who would have removed the hairs from the heads before delivering them, these were four hirsute objects that only a Samson could love. Franey tried knives, razors, and scissors to remove the hairs — he even tried to singe them off over a gas burner.

Nothing worked. Finally, in a fury, he told his son, Jacques, to throw the things to the gulls — thus setting off one of the oddest Hamptons causes célèbres ever. The severed heads washed up not far down the beach of Gardiner’s Bay, where a child walking on the sand discovered the ghastly remains and ran screaming to her parents.

The media went bananas; the police went nuts. Rumor ran wild — crazed hippies! ritual sacrifice! — until, a week or two later, a woman who’d been an occasional dinner guest at Craig’s suggested that detectives check out the well-known food writers living not far from the crime scene.

Craig and Pierre owned up. The following year, they published Veal Cookery, one of many books they wrote together, complete with a tortuous recipe for tête de veau.

Despite throwing a countless number of elaborate buffets, picnics, clambakes, wedding receptions, and birthday parties for friends almost every other sum- mer weekend, the two somehow managed to maintain an outsize presence in their adopted town. From the late ‘60s to the mid-’80s, they seemed never to turn down a plea to appear at an event benefiting an East Hampton cause.

A few examples, from many: In July 1976 they judged the Best Cake contest at East Hampton Town’s Bicentennial Parade. In December 1966, they demonstrated how to make holiday appetizers at Ashawagh Hall in Springs, and again the next day at the John Drew. (“What they cook will be awarded to a few lucky winners. The recipes will be divulged freely.”) In September 1982, they not only prepared food but served as waiters at the Springs Improvement Society and Montauk Village Association annual fund-raisers. For years, they signed cookbooks to benefit Southampton College, and wrote college recommendations for East Hampton High School students seeking careers in the culinary arts.

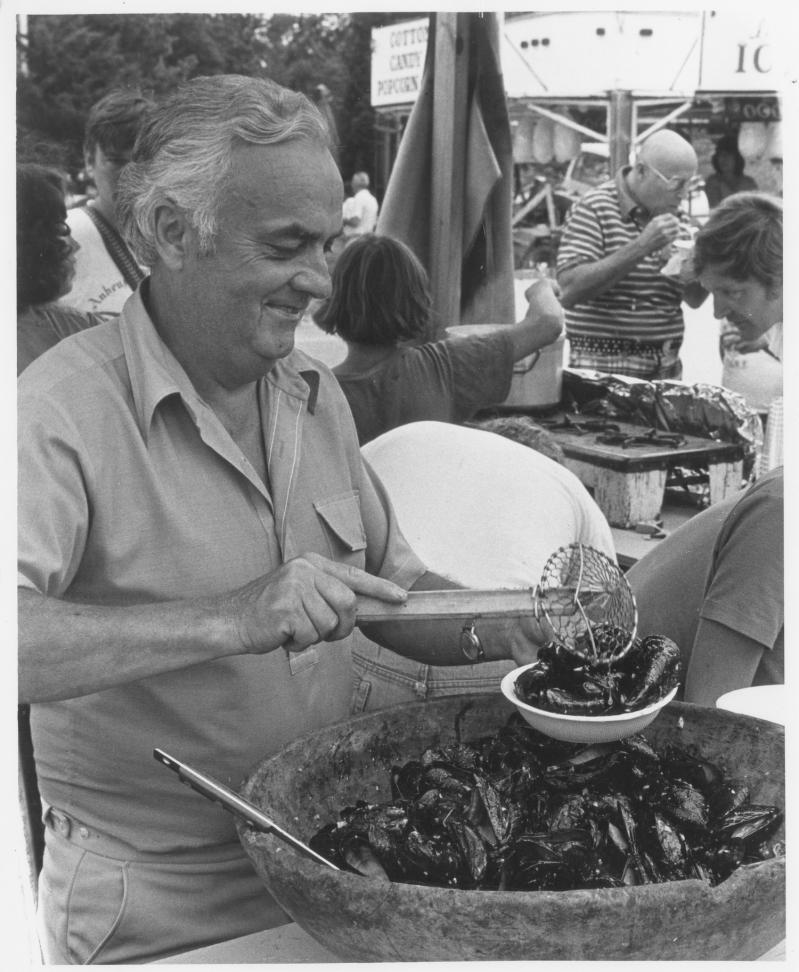

Most of all, on the first weekend of August, they could be counted on to show up at the Fisherman’s Fair in Springs. “Fabulous Seafood on Premises: Craig Claiborne and Pierre Franey specialties!” promised the posters, and the pair did not disappoint. They arrived early, donned long aprons, opened untold numbers of bivalves, and stayed to the end, or until the last slice of their clam pies was gone.

In 1974, CBS asked them to create a “typical American meal” for a July Fourth television spectacular. Craig suggested a New England clambake, featuring lobsters from the men’s own pots in Gardiner’s Bay, and they agreed to be filmed out on the water, harvesting them. The day before the filming, they bought six live lobsters from Stuart’s fish market and planted them, surreptitiously of course, in the traps. The camera crew was ecstatic when the stars of the show pulled up the first trap and “discovered” two lobsters in it.

There was just one hiccup: They’d forgotten to remove the rubber bands from the claws. The lobsters were de-banded and re-sunk, and the episode re-shot.

Not all their escapades were fun and games. People complained bitterly about a few binges, accusing the pair of over-the-top indulgence when all over the world people were starving. For the lucky guests, though, the feasts, even without the food, were magical. After attending one such blowout in June 1977, Helen Rattray wrote in The Star that “there were others in the kitchen, I know, who can chop dill with panache, but when Pierre chops dill it is in a class apart, a utilitarian art transformed by consummate skill, aplomb, and pleasure in the doing, into a beautiful performance.”

A year or two before that party, an infamous trip to Paris had earned the two a torrent of criticism. Claiborne, much to his surprise, had made the winning bid on a fund-raiser for Channel 13: dinner for two anywhere in the world, no limit on the tab, all paid for by American Express. He took Franey with him, naturally, and between them they managed to spend $4,000 on a five-hour, 31-course meal in Paris, which he later described in loving detail in The Times, causing widespread indignation.

Vatican City had the last word: “Scandalous,” said Pope Paul VI.

Two years later, for another PBS benefit, they atoned by donating four dinners, and entertained the winners with an elaborate spread at Craig’s new house on Clamshell Avenue in East Hampton.

On Sept. 9, 1982, in a yellow-and-white-striped tent on the grounds, Claiborne celebrated his 60th birthday, with a guest list of several hundred, including dozens of distinguished chefs and food writers, one of whom called it “the food orgy of the century.” Jacques Pépin manned the spit-roast, Alice Waters offered the guests strawberries, and Maida Heatter, the era’s illustrious “Queen of Cake,” brought one in each hand.

Of his innumerable holiday celebrations, Claiborne seems to have been fondest of New Year’s Eve. “I love that night,” he confessed in his autobiography. “In times past, when I have been unbelievably poor, I have on that night felt like the greatest of pashas, the epicure’s epicure.” His New Year’s Eve affairs were black-tie buffets, with Christofle silver and Baccarat crystal, for about 75 guests. A typical menu featured suckling pig stuffed with apples, roast goose stuffed with chestnuts, and a venison ragout. Some of the guests — longtime neighbors, or those who’d driven long distances to be there — were invited to return hours later, on New Year’s Day, for cold leftovers, caviar, and unlimited Champagne.

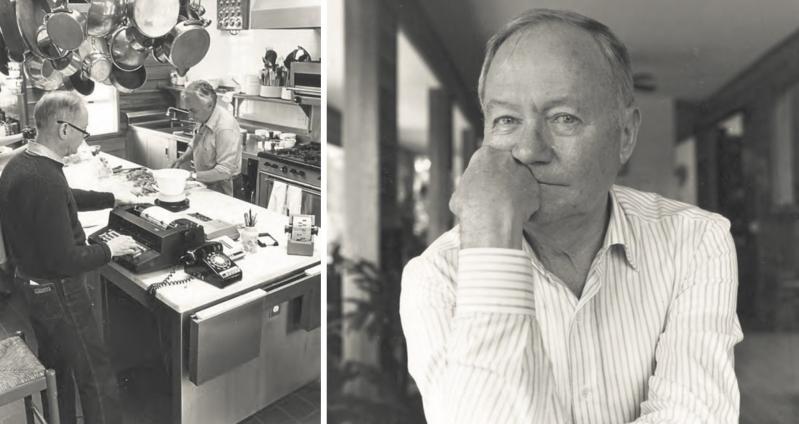

Claiborne’s East Hampton house, once described as “a kitchen with a bedroom and bathroom attached,” was designed, for some inexplicable reason, with its king-sized kitchen (which had a stainless-steel oven for Chinese roast pork and a clay one for Tandoori, along with a six-burner Garland gas range) facing landward, rather than toward a stunning view of Hand’s Creek and Three Mile Harbor.

According to the Times food critic Florence Fabricant, whom Claiborne befriended early in her career, the house also had a small creek-facing study, where Craig, as his health declined, wound up sleeping, leaving the bed- room for guests. Pierre and Betty, Ms. Fabricant said, had tried unsuccessfully to dissuade him from moving there, and they were right. He was never really happy in the East Hampton house, and put it up for sale in 1987, when he’d just left The Times for good.

Toward the end of his life, Claiborne continued to write, lecture, and travel, all the while drinking a lot, even as his health worsened. He died in 2000, aged 79, at St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital in Manhattan, leaving his books and papers to the Culinary Institute of America.

He did manage to outlive Franey, his old friend and collaborator. Pierre and Betty were on a culinary cruise in 1996 aboard the Queen Elizabeth 2, when, en route to England, he had a stroke after giving a cooking demonstration. When the ship docked, he was rushed to a hospital in the port city of Southampton. The couple had planned to visit family members in France before returning to New York, but he never regained consciousness. He was 76.

Franey is said to have loved local bay scallops, which he made with a simple garlic cream sauce and served over pasta, and batter-fried spearing (whitebait), more than almost anything else. In 1995, the year before he died, his PBS show, Cooking in France, won the James Beard Foundation Award for best cooking show on television.

Franey went on hunting and fishing as long as he could, probably more for food than for sport. One day in the early ’90s, while driving in Springs, he hit a deer. He wrestled the carcass into the trunk, so the story goes, and drove home, likely thinking about venison recipes. When he opened the trunk, Jacques Franey recalled years later, the deer leapt out and dashed away.