Ketamine, an illegal hallucinogenic party drug, also known as Special K, might hold the key to treating 10-year-old Rowland Egerton-Warburton of Water Mill, who was diagnosed in 2016 with ADNP syndrome, a rare neurodevelopmental disorder.

“Within about 45 minutes after the ketamine infusion, I noticed subtle changes. But the next morning when he woke up, and I unzipped his special safety sleeper bed, and I said, ‘Good morning, Roly,’ he said, ‘Mommy,’ completely unprompted. He is a nonverbal boy — I’ve never heard him say that! It was unbelievable. I was in tears,” said Genie Egerton-Warburton, Rowland’s mother, recalling the after-effects of a small clinical trial conducted in 2020 by the Seaver Autism Center, part of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital in Manhattan.

The study, the first-ever drug trial for this extremely rare syndrome identified in 2014 and believed to affect only approximately 400 children worldwide, included Rowland and nine other children with mutations in the ADNP gene who were between 5 and 12. They received one low-dose infusion of ketamine for 40 minutes and were monitored for four weeks, undergoing safety checks, clinical evaluations, and biomarker studies using electrophysiology and eye tracking.

Rowland’s mother, seated in the family’s Water Mill house, continued to describe the immediate results of this groundbreaking study: “The next morning, when we were taking him to Mount Sinai for a check-in, we were walking down the street and I noticed that he was looking at cars. He was able to notice an airplane in the sky, whereas he had never looked up before. He had a whole new sense of awareness — he was able to navigate down a city street without bumping into anybody and he was cognizant of people passing by him as opposed to maybe being in his own world. The maladaptive behaviors lessened for about three days, meaning less pinching, less pulling hair, less aggression. It was almost like he had a feeling of calm. And I’m getting kind of emotional about it because I wish I had that kid back right now.”

The Star first documented Rowland’s syndrome in 2018, highlighting his family’s tireless campaign to help him function, develop, and eventually become more independent. ADNP, also known as Helsmoortel-VanDerAa syndrome, is caused by a mutation in the activity-dependent neuroprotective protein gene that regulates brain formation, development, and function. The mutation can cause problems with the cardiovascular, endocrine, immune, musculoskeletal, and gastrointestinal systems, vision, hearing, growth, feeding, and sleep. It can also cause delays in intelligence, speech, gross motor, fine motor, and oral motor planning, and oftentimes causes behavior disorders related to autism. As such, Rowland is in need of a daily array of specialists, which, at the moment, he receives in a piecemeal way through home-based services.

Understandably, for Ms. Egerton-Warburton and her husband, Jamie, the prospect of a readily-available treatment in the form of a repurposed drug that’s relatively inexpensive fuels their desire to keep pushing for the next phase of ketamine trials.

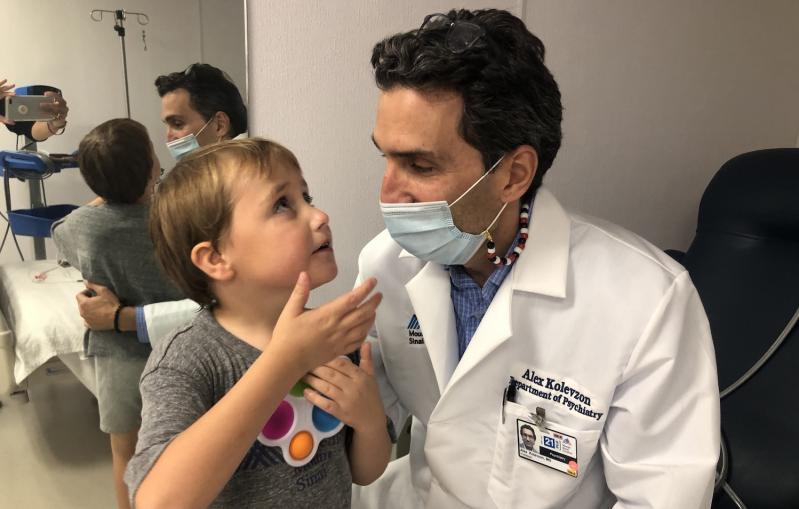

Alexander Kolevzon, M.D., the clinical director of the Seaver Autism Center in Manhattan, who was at the heart of the 2020 ketamine trial, explained the results. “They were very, very promising first and foremost and no kids had serious adverse events,” he said by phone. “We looked at symptoms like social symptoms, sensory sensitivity, hyperactivity, repetitive behaviors, all the kinds of features that we see in kids of ADNP syndrome. And we saw a lot of improvement across a lot of different measures, including a nice alliance between the parent reports and the measures that the clinicians use. In other words, clinicians’ impressions were aligned with the parent impressions,” he said.

However, Dr. Kolevzon stressed the need for “a larger controlled study where we recruit a larger number of rotations, probably at least 30, with repeated dosing. So instead of just a single dose, we would probably give kids doses twice a week for about four weeks. And, we would also have a placebo control. So half the kids would get active medicine and the other half would get a saline blood placebo,” he explained. Dr. Kolevzon also said that the first trial did not use a placebo, which meant that, “Me, as a clinician, and the parents all knew that the kids were getting the active treatment. So that already gives a lot of bias. It inserts a lot of expectation. . . . We need to do a larger controlled study,” he explained.

This potentially groundbreaking development in treating the ADNP syndrome with ketamine, which is also used to treat depression, came about from an unusual source: an artificial intelligence system called mediKanren. In 2019, after only a few seconds of scanning millions of biomedical abstracts that linked existing compounds and the ADNP gene, the A.I. tool pinged the party drug — also known as the date-rape drug — as a possible key to treating the syndrome.

Of course, administering a highly addictive drug to a child inevitably raises eyebrows. “There are concerns about abuse,” admitted Dr. Kolevzon. He had hoped that the larger-scaled, phase two trial could be eventually administered by parents or caregivers at home, following initial instruction and supervision in the clinic. However, “the F.D.A. is not comfortable with that plan,” he said. “So we are now in the midst of trying to figure out whether we want to hire a visiting nurse service to go into the homes to reduce the need for the families to travel. Or, whether we simply have to have the families come in to the clinic.”

Rowland is “a pretty healthy boy, all things considered,” said Ms. Egerton-Warburton. He is also a boy with receptive language skills, meaning he can understand much of what is being said around him. Following a prompt, he was able to high-five and say the word “car,” as he was about to go on a drive.

“But he just can’t talk. That to me is the hardest thing. And that drives me every single day to find a treatment, to try any treatment for him. Because if there’s something that can unlock his brain, I want to find whatever that is,” his mother said.