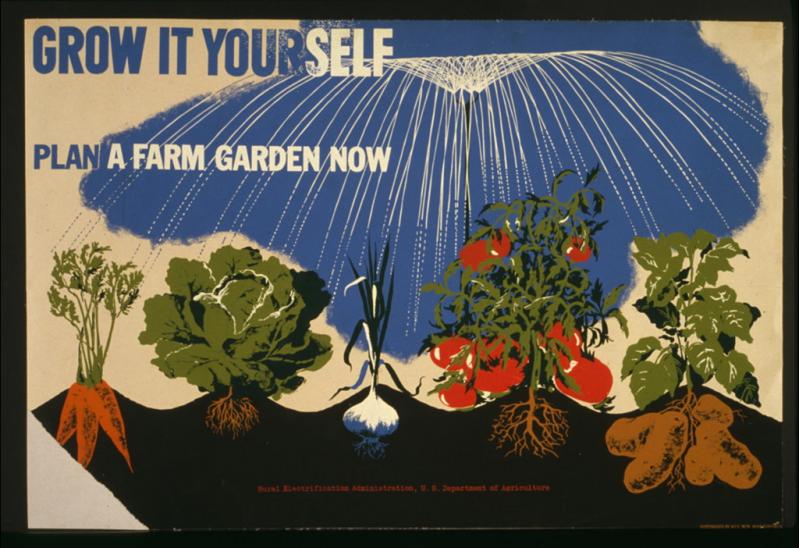

This year I finally planted my victory garden. My coronavirus home farm, inspired by the victory gardens of World War II.

During the war, the government rationed food (like sugar, eggs, cheese, meat), and as there were difficulties moving fruits and vegetables to markets, Americans were encouraged to plant and grow their own victory gardens. More than 20 million of them were planted in backyards, on front porches, in empty lots, on rooftops, fire escapes, windowsills. The United States Department of Agriculture estimates that 9 to 10 million tons of fruits and vegetables harvested from the gardens during the war made up approximately 40 percent of produce in America at that time.

In this time of war against the coronavirus and limited access to stores, food markets, and supply chains, with schoolchildren at home underfoot and trouble even getting out of our homes, it was the perfect time to grow a home farm, my own victory garden, and I did have a fairly successful one. With my bounty, I insistently gave giant zucchinis and cucumbers to friends. We are still dining on the tomatoes and harvested onions. Eggplant, peppers, and carrots are still growing.

My love affair with gardens and farms began as a 3-year-old living in Brooklyn. My mother grew up in Ferndale, N.Y. (heart of the Catskills), above the butcher shop her parents ran. She taught in a one-room schoolhouse, which is preserved today. When I was 3, our family got to visit Ferndale, the cousins who lived in bungalow colonies, the chicken farms, and we spent some time at a hotel in the Borscht Belt. Being pale and easily sunburned, I sought relief from the sun. I fell in love with greenery, with growing things in gardens, with visiting farms and seeing chickens.

Locally, when my own children were young, we began farm harvests with “U-pick” strawberries in June, pumpkins and apples in the fall. In the summer, we joined the co-op Quail Hill Farm in Amagansett to harvest our own weekly allotment. On Long Lane in East Hampton, we visited the chickens and sometimes goats at the Iacono Farm and, years later, in 2001, helped get the East End Community Organic Farm going by renting our first vegetable garden plot of 20 by 20 feet. EECO Farm still rents 125 garden plots a year to community gardeners.

When my daughter, Chloe, was 3, we went to harvest our weekly share at Quail Hill. Having come from the city, where one had to watch children with eyes in the back of your head, letting kids roam in fields and gardens was the epitome of freedom. (These were the days before we knew about ticks, and children were free to frolic in the grass.) While I was busy cutting flowers, her brother, Zach, was jumping over hay bales, and her father, Evan, was harvesting lettuce, Chloe discovered the raspberry patch. And then she disappeared. For maybe twenty minutes she was out of sight. (Okay, I knew where she was and decided to just let her be.) She ate her way from one end of the patch to the other, emerging with berry smears on her face and a smile, a look of, well, more than satisfaction. This was bliss! For her, for me.

The thrill of picking has never left me. It’s magic. I oversaw the harvesting of thousands of pounds of vegetables and fruits by hundreds of school kids when I ran the Gleaning Project. It was conceived when my family lived in Greenwich Village and became involved with the Penny Harvest, created by Teddy Gross, which had children ask neighbors for their surplus pennies, to be donated to organizations that helped the homeless. In our high-rise apartment building alone, my two little munchkins collected nearly $400 in pennies and spare change. When we moved from the city to the country (East Hampton), our city friends teased, “What are you going to harvest there?” My knee-jerk response: “We’ll harvest the real thing.”

It took a year of meeting with farmers, food pantries, and schools to organize the harvest and the delivery of its crops. Once I had convinced Island Harvest, a not-for-profit food rescue organization, to sponsor the Gleaning Project, thereby enabling insurance coverage for harvesting and providing the farmers tax-deductible receipts, it was a go.

I began by asking local farmers if they had or expected to have any surplus crops that might go to waste. John White, Jim Pike, Rick Wesnofske, and Larry Halsey were my star farmers, alerting me to their surplus of beets or green beans or potatoes or tomatoes. Then I organized a group — teachers or parents at schools, clergy in churches and synagogues, leaders in fraternal organizations — to be ready and willing to harvest on a week’s notice. Teachers from the Hampton Day School, public schools in Tuckahoe, Springs, East Hampton, and Bridgehampton, the Ross School, and religious groups like the Jewish Center of the Hamptons and the East Hampton Presbyterian Church supplied a pool of ready volunteers to deliver the harvest to food pantries, shelters, and day care and senior citizens centers. I ran the operation out of my Ford Explorer and had phone numbers written on matchbooks.

The children were happy to have a fun field trip and curious to learn about how food actually grows. The farmers were able to clear their fields to ready them for the next planting. Last, Island Harvest was able to offer receipts for tax-deductible farm donations. It was a win-win for everyone.

Over the years, we harvested thousands of pounds of produce, always in the fall. Most fall crops, if harvested correctly, could last a few days to weeks when stored in empty cardboard produce boxes recycled from supermarkets like King Kullen. Once filled, the cartons, averaging 30 to 40 pounds, were delivered by volunteers — apples, beets, tomatoes, leeks, broccoli, cauliflower, brussels sprouts, peppers, eggplant, green beans, spinach, mizuna, arugula, carrots, potatoes, potatoes, potatoes. Did I mention potatoes?

And I’m still at it. Just Sunday, I joined a group of 25 kids and adults, masked and socially distanced, who in less than an hour gleaned 900 pounds of acorn, spaghetti, and delicata squash from Pike Farms in Sagaponack. The group, members of Temple Adas Israel in Sag Harbor, then distributed the 30 boxes by the carload to food pantries in Springs, Wainscott, Sag Harbor, and Bridgehampton.

It was a great way for youngsters to help clean up a farm and, ultimately, provide fresh produce for neighbors in need.

Rivalyn Zweig is a photographer living in Sag Harbor.