Mary L. Trump, a clinical psychologist and the former president’s niece, has provided important insight into her uncle’s denial of the 2020 election results. In a Showtime interview in October she pointed out that in the Trump family losing and failure are unacceptable. They are “akin to a death sentence.” One can only be a winner.

Trump’s actions with respect to the election, including his role in the events of Jan. 6, are unprecedented. But his attitude toward winning, while extreme, is hardly new. Winning is a supreme value in American culture.

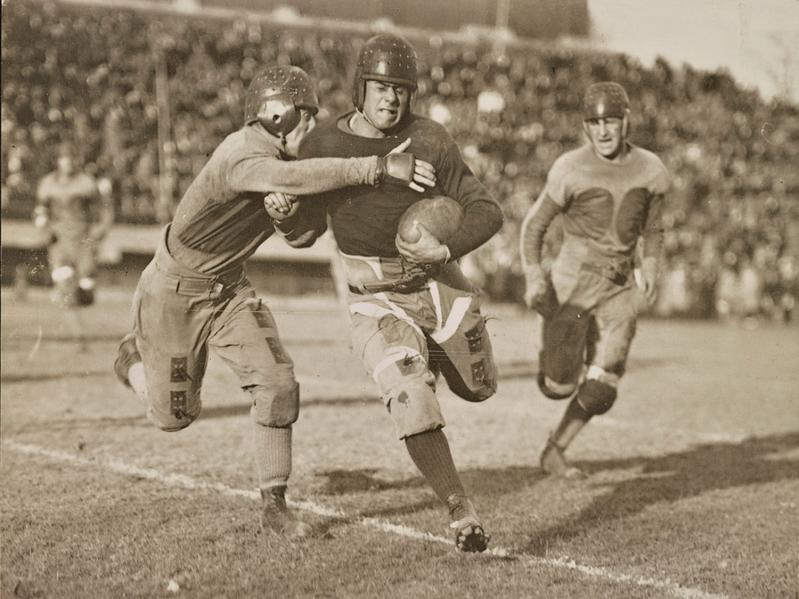

Our obsession with winning is perhaps most apparent in sports, exemplified by the remark by the football coaches Red Sanders and Vince Lombardi: “Winning isn’t everything; it’s the only thing.”

Failure can be devastating. After Mikaela Shiffrin fell in the 2022 Olympic slalom, she sat in the snow crying, with her head in her arms, for 20 minutes. I doubt many people — and certainly not the television commentators — thought she was taking the defeat too seriously.

Victory is no less important in American movies, which shape so many people’s ideals. Audiences expect heroes to win, and they almost always do. Even though Rocky, for example, lost the fight in the first film, he emerged victorious in the sequels.

Our society constantly asks us to compete — for the corporate contract, the lead in a play, the scholarship, the county fair blue ribbon. No facet of life is immune. And we are encouraged to dream big. As Frank Sinatra sang in “New York, New York,” the goal is to become the king of the hill. Conversely, one of the worst insults is to be called “a loser.”

I have learned about the importance of winning from my undergraduate psychology classes at City College of New York, where I taught from 1970 to 2021. To stimulate discussions, I frequently asked the students to imagine they are offered two paths. The first leads to wealth and status. One defeats all rivals, but one must neglect one’s family. The second path results in a rather undistinguished job with a modest salary, but the individual gains loving family bonds.

The majority consistently chose the first option. Although they understood the importance of family, they wanted to be at the top of the social ladder.

My survey was informal, and my students were predominantly from working-class and immigrant families, so the desire for upward mobility may have played a role. But I noticed that those from middle-class families usually made the same choice.

A psychoanalyst who provided many insights into the effects of competitive ambition was Karen Horney. Horney (pronounced “Horn-eye”), who came to the U.S. from Germany in 1932, was struck by how social pressure to become the best causes emotional distress. She observed that only a tiny number of people can ever be at the top of their fields, so the rest must deal with defeat and failure. The result is painful feelings of inadequacy.

To an extent, people can escape feelings of inferiority by identifying with winning teams. Many U.S. citizens also gain self-esteem from patriotism, feeling part of the greatest military power on earth. But all teams lose at some point, and the U.S. hasn’t been victorious in most of its recent military campaigns. Deep down, feelings of inferiority persist.

It isn’t possible to immediately eliminate our obsession with winning, but here are two things we might do when talking with young people and friends.

First, praise examples of sportsmanship. When, for example, the Boston Celtics lost last season’s N.B.A. championship, Jayson Tatum, the Celtics’ young star, was one of the few players on either team who remained on the court after the final game to compliment his opponents. We should call attention to such behavior, for it demonstrates that defeat can be accepted with dignity and graciousness.

Second, look for opportunities to ask questions that pit winning against other goals. “What is more important, winning or doing one’s best?” “What makes for a well-lived life, victories or serving others?” Thinking about such matters can help put winning in perspective.

William Crain is professor emeritus of psychology at City College of New York and a part-time Montauk resident.